One can understand feminists targeting Salman Khan for his alleged insult to women with his ‘rape’ analogy. But for the National Commission for Women (NCW) to summon the actor with the threat of suing him is to rob whatever little dignity there is left in this otherwise ineffective and toothless institution.

When is the last time you heard or saw the NCW do something meaningful or memorable for women? Most of its chairpersons have been political appointees and have used the office to emote profusely while doing very little constructive work. It is also a poorly administered institution lacking fine-tuned systems for responding to challenges that women face today. Therefore, all we get from the commission are knee jerk responses to trivial events rather than a well-thought-out vision and programme of action for improving the lot of women.

At a time when we are being confronted with gruesome reports of gang rapes of women and kids, of thousands of children being abducted every year for inhuman forms of trafficking, millions of women being sucked into the flesh trade every year, countless women becoming victims of cybercrimes, the NCW had to pick up the most ridiculous issue to flex its muscles. Its chairperson is acting as though a man uncritically using the word ‘rape’ as an analogy commits a far more heinous crime than actually raping women. Why else is it that we have not seen the NCW issue any threats to actual rapists?

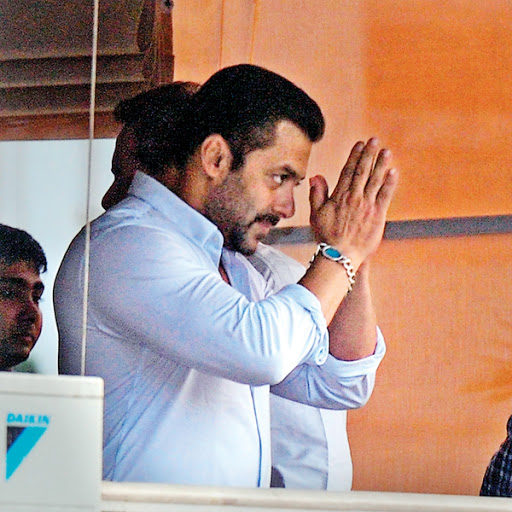

What Salman said: Before I offer my reasons for coming out in defence of Salman Khan, let me refresh the readers’ memory by quoting, from the original source, the exact statement as well as the background of the controversial remarks. In response to a reporter’s question on what kind of effort he put in to get the character of a wrestler in a soon to be released film physically right, Salman said:

“It’s a tough process. You need ample training like the wrestlers. The training Aamir Khan and I have been through is similar or probably a little more than what the wrestlers go through. If we didn’t do it, we wouldn’t be able to fight convincingly in the ring…. I underwent weight training. Then I perfected the moves. I spent 2-3 hours in the day practising those because in the film, I go from the village level akhada to the mat-based ring and then the MMA arena. So I had to do a lot of punching and kicking. I had to be convincing or else I’d look like a fraud.”

The reporter then comments, “The shoot must have been gruelling…” To this Salman responds:

“While shooting, during those six hours, there’d be so much of lifting and thrusting on the ground involved. That was tough for me because if I was lifting, I’d have to lift the same 120-kilo guy 10 times for 10 different angles. And likewise, get thrown that many times on the ground. This act is not repeated that many times in the real fights in the ring. When I used to walk out of the ring, after the shoot, I used to feel like a raped woman. I couldn’t walk straight. I would eat and then, head right back to training. That couldn’t stop.”

Far from finding these remarks offensive, I was actually moved by them.

Salman did not make a casual, light-hearted comment about rape, nor refer to the crime as an enjoyable sport. He offers his analogy to refer to the kind of physical pain and torture an actor has to go through in order to do those macho roles involving what is light-heartedly referred to as Bollywood style dishum-dishum, which many youngsters think is a lot of fun. But describing the gruesome battering the body takes to prepare for, rehearse and enact those roles for the camera, Salman is in fact de-glamorising the entire exercise. He describes the vulnerabilities of screen heroes in real life and how such situations can even lead to grievous and life-threatening injuries, as they did in the case of Amitabh Bachchan on the sets of the blockbuster film Coolie.

If a man who has been put through the gruelling experience described by Salman Khan compares it to the physical battering of a raped woman, the analogy is not so inappropriate as to cause a media uproar.

True, rape is far more than physical trauma – it’s also a violation of a woman’s selfhood and dignity – whereas Salman is undergoing that gruelling predicament voluntarily, for money, name and fame. But the seriousness of the occupational hazard should not be undermined just as the occupational risks involved in being a pilot flying and dropping provisions to soldiers based in Siachen can’t be lightly dismissed by saying, “Well, he was paid for the job and chose it voluntarily”. Similarly, no one is dismissive of the risks taken by a mountaineer going up Everest by saying he is well paid and chose to climb the treacherous peaks for name and fame.

Analogies in perspective: Moreover, analogies – whether negative or positive – are not meant to be taken literally. For instance, if a male poet compares the beauty of his beloved to the radiance of a full moon, it doesn’t mean the woman has to have a perfectly round, silver-blue face which can be taken as a replica of the moon as seen from the earth. When you say someone eats like a pig, it doesn’t mean that the man actually eats muck.

While Salman used the rape analogy to describe a life-threatening situation during shooting, in fact, the analogy is often used light heartedly to refer to a range of situations, not just by men but also women. I have heard young female students describe the experience of sitting through the classes of aggressive teachers who act like bullies as “intellectual rape”. Recently, a well-known author talked about the “rape of the rupee”. Environmentalists often use the phrase “rape of Mother Earth” to describe the callous manner in which governments, corporates and other vested interests are plundering and vandalising this planet unmindful of its consequences for future generations.

Alexander Pope’s satirical poem Rape of the Lock is still taught as a literary classic the world over, including in India, even though it uses the term “rape” to poke fun at the foibles, vanities and fantasies of 18th-century British women. Had it been a 21st-century Indian male who wrote a similar poem using the term “rape” in a satirical manner, the NCW would have stopped at nothing short of seeking the death penalty for him! Even with Salman, many feminists have menacingly declared that a “mere apology” won’t do. Who knows, with the majestic women’s commission leading from the front, what punishment they have in mind. Would the NCW dare demand a ban on Alexander Pope’s writings?

Unfortunately, by making a mountain out of a molehill and hyper-ventilating for days on end on prime time television, self-appointed thekedars of women’s rights have made activist women a laughing stock of the nation. Those who cry for frivolous reasons have created conditions for a serious backlash on women’s issues.

The most bizarre part of this entire saga is that most of those who are baying for Salman’s blood go hysterical when it comes to government censorship over pornography or even minor cuts in films like Udta Punjab, which are replete with foul, highly sexist abuses. They don’t want censorship over pornography – which is highly demeaning to female dignity and filled with gross forms of violence on female bodies – but they support “verbal censorship” of the most tyrannical variety in our daily conversation. Any attempt by state institutions to curb vulgarity and violence is rejected as unwanted ‘moral policing’ and a sign of authoritarianism. But TV anchors and sundry feminists think they have a god-given right to impose their moral code and censorship even on casual conversations.

We must say a firm ‘No’ to this fake and frivolous manifestation of political correctness that is distorting public discourse and distracting attention from serious issues.

And my sincere advice to Salman Khan: Please don’t buckle under the illegitimate pressure the NCW is putting on you to apologise publicly for your comments.