This article was first published in Manushi Journal, issue number 30 of 1985.

In mid-June of 1985, I took a trip to Punjab to see for myself how far the situation in Punjab matched what one read about it in the press. Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale had been killed in the course of Operation Bluestar on June 6, 1984. The attack on the sacred most shrine of Sikhs in Amritsar, namely Shri Harmandir Sahib ordered by Indira Gandhi had enraged both Hindus and Sikhs of Punjab because reverence for the Golden Temple and Sikh Gurus is universal not just in Punjab but all across India. However, this gave a big handle to Pakistan’s ISI which turned anti-Congress, anti-Indira sentiment in Punjab into an anti-India insurgency in Punjab using the Khalistani rhetoric with intent to force yet another break up of India. Most of the national media, as usual, readily succumbed to providing highly censored accounts. Even though there had no Hindu-Sikh riots in Punjab, Congress Party worked hard to create communal estrangement between the two closely interlinked communities using Khalistani rhetoric to scare Hindus even though the Khalistani poison had been injected into Akali politics by Indira Congress itself. ( Read the interview with Sant Longowal on this issue at Blast from the Past: Role of Indira Congress in injecting Khalistani poison to destroy Akali Dal). Since the main purpose of my visit was to meet the Sant Longowal, widely believed to be the moderate face of Akali politics ill at ease with Bhindranwale, I shared impressions of my meeting with Longowal ji and my stay in his Gurudwara cum home at Longowal village in the following article. Tragically Sant Longowal was assassinated by Khalistani hotheads on August 20, 1985, within two months of this interview which was possibly his last informal conversation with a journalist. At that time there were no video cameras. But I made sure to audio record his interview which I translated from Punjabi myself.

I was really surprised to find that my visit to the Longowal gurudwara provoked bizarre reactions from most of my Hindu friends and acquaintances. They seemed to be as shocked as if I had come back alive from a sojourn in a lion’s den. My own experience of that place was so dramatically different from what people imagined, that I feel compelled to write about the experience in some detail.

For the last few months, Sant Longowal had been consistently demanding an enquiry not only into the 1984 anti-Sikh riots in north India but also into the genesis of terrorist violence in Punjab. Time and again, he asserted that, if the government ordered such an enquiry, the Akalis would provide evidence that much of the violence that was being attributed to extremist Akalis was in fact instigated by Congress (I) factions in Punjab. Prior to this trip to Punjab, I had discussed the issue with some civil liberties activists in Delhi. We had come to the conclusion that even if the government did not agree to institute an enquiry, a group of independent citizens could be called upon to do the job. One of the questions I wanted to explore with Sant Longowal was whether he and his party would assist such a citizens’ enquiry team.

I was accompanied on this trip by a woman friend, who had so far not been involved with Punjab politics. Before leaving for Punjab, we tried to contact his party office in Amritsar in order to fix up an appointment but we did not succeed. His partymen in Amritsar could not say for sure when and where we could meet him in Amritsar. He was constantly travelling from one place to another, addressing meetings in rural areas and small towns of Punjab. Telephone connections being what they are in most parts of India, his partymen in Amritsar could not keep track of all his movements.

e were told he might be coming towards Amritsar on a particular date. We decided to take a chance and begin our intimation or appointment. We were informed that since he used the gurudwara near Longowal as his base, he was likely to be there sooner than at Amritsar, even if he was constantly on the move. trip with Amritsar.

On reaching Amritsar, we found that Longowal’s plans had changed and he was not likely to be anywhere near Amritsar for the next couple of days. It was impossible to get through on the telephone to his headquarters in village Longowal. So we were advised to take a chance and go there, without bothering about prior intimation or appointment. We were informed that since he used the gurudwara near Longowal as his base, he was likely to be there sooner than at Amritsar, even if he was constantly on the move.

We took the early morning train to Ludhiana, from there a bus to Sangrur where we had to wait several hours to get a connecting bus to village Longowal. We reached there at about 2.30 p.m., in the blistering heat. To our dismay, we found that the gurudwara was at least three kilometres away from where we had alighted. While we were waiting for some form of transport, some men standing near the bus stop got into a conversation with us. They were curious to know where we were from. When we said we were from Delhi, they assumed we were journalists. However, two of them asked me if I was from the Congress (I). I was alarmed that I should be so mistaken and wondered what had caused it. It was apparently my white khadi kurta and salwar which created this impression. Since it was not possible for me to change clothes at this point, I became a little apprehensive of giving a wrong impression to the people in the gurudwara as well.

As it was, we were very hesitant about how we would be received because we were arriving without any prior intimation. I also had apprehensions that we might not be taken seriously as we were women. We had no impressive press cards or letters of introduction. Even in normal times, it is difficult to approach important political leaders without the help of intermediaries. Sant Longowal faced grave danger both from Sikh terrorists and from certain Congress (I) elements in Punjab and we expected that he would not be easily accessible.

Anyway, it was too late for such doubts. So we hired a tempo and proceeded to the gurudwara. The road went through dry, parched countryside. When our tempo reached the gurudwara, the driver stopped the vehicle near two young men posted as guards, who were sitting on a chaj premises the two boundary walls had a big opening which acts as the main entrance. We walked to the inner compound.

We saw a small group of men of differing ages, sitting and talking in soft, quiet tones, to each other, under the shade of a tree. On seeing us, no one rushed towards us. They continued chatting. We looked around for something that looked like an office. There was nothing of the kind. All we saw was a row of about 10 rooms with a corridor in front just as in school buildings. The doors of the rooms opened into the corridor and they faced the inner compound. The compound had two handpumps and several trees and shrubs, many of them in the growing stage. The compound and the plants looked well-tended.

The row of rooms where the sewadars live The row of rooms where the sewadars liveand work. The last room in this row was Sant Longowal’s room. |

We walked to the men sitting under the tree and asked if we could talk to the person in charge of the gurudwara. “Everyone is in charge here”, one of them replied, “Talk to anyone you like.” In the meantime, two young men came out of a room and offered us water. We told them we had come to meet Sant Longowal. “Santji is not in at the moment. He will come back sometime in the evening.” We asked: “Can we wait for him here?” The young man replied in a friendly voice: “This is the Guru’s house. Everyone is welcome here at any time.” They asked us no questions, whatsoever as to who we were or why we wanted to meet the Sant. One of the young men led us to a room, set up two big string beds for us and asked us if we would like to have lunch. We assured him we had eaten on the way. He offered to make some tea for us.

There was something very unusual in the way we were accepted in the gurudwara. These young men whom we talked to, simply offered us this room they said we could stay in. They did not seem to need anyone’s permission or approval. We were tired and lay down on the beds. The room we were in was like all the other rooms, absolutely bare in its simplicity. As far as I can remember, the brick walls were not whitewashed. They were covered with grey cement plaster. Apart from the beds, there were a few hooks on the walls, on which men’s clothes were hanging, and a few open cement shelves with odd things kept on them— the sparse belongings of the Sewadars. The only noticeable things on those shelves were two Gurbani Gutkas wrapped in satin, as is the custom.

The room, like all the others, had an electric bulb and a ceiling fan, and large windows. The whole place had an air of rustic simplicity without any ostentation. The effortless austerity of the place seemed to be geared towards ensuring that the inhabitants did not suffer any needless discomfort. There seemed to be no fetishising of austerity of the kind that is often witnessed in monastic communities.

| When I tended an apology for causing him(Sant Longowal) trouble by occupying his room, his response was, “Why do you call it my room? It belongs to the Guru just as everything here does.” Saying so reflected his humility and it humbled me. |

As we lay down to rest, there was a soft knock on the door and an elderly man came in to take his clothes hanging on the hooks. I mumbled an apology: “Sorry, we have inconvenienced you by occupying your room.” His voice was gentle: “Why do you call it my room? It belongs to the Guru just as everything here does.” He talked to us briefly but asked us no questions, displayed no curiosity or suspicion.

Tea was brought in by another young man in his early twenties. He was polite, shy and softspoken like the first one. He asked if we were comfortable and whether we needed anything. He indicated the location of the toilets, brought a new bar of soap for us, and cleaned the room used for bathing, even though everything seemed already clean. Once again, there were no probing questions or suspicious looks.

This was so unlike what one usually confronts travelling anywhere in the country, especially in the countryside, that instead, I asked him questions such as how long he had lived in the gurudwara, what the nature of his job was, how many men lived there as Sewadars. Every question was answered without any uneasiness or any attempt to be cautious. He told me that about 15 Sewadars live in the gurudwara. All of them belong to neighbouring villages. The younger men were educated, most of them in village schools and colleges. Some had studied up to matriculation, a couple of them were graduates. One of them had a master’s degree. He was the one who had first brought us to the room and set up the beds for us.

He said that at an early age, he had decided to devote his life to the Guru, but had continued studying even after he joined the gurudwara as a Sewadar. Apart from helping in the general running of the gurudwara, he also took care of Sant Longowal’s needs and acted as his guard. What about Santji? What kind of schedules did he keep? What was the nature of Sant Longowal’s current political activity in Punjab? Again, the answers were clear and informative. He explained how, for the last few months, Santji was constantly travelling from one part of Punjab to another, in an attempt to conduct an intensive mass contact campaign. He went wherever he was invited—not just to gurudwaras but also to temples. He spoke not only to Sikh gatherings but also to Hindu gatherings in Punjab. Many of these meetings were scheduled and fixed in advance in which case the people at this gurudwara knew of his programme and his movements. But he often made unscheduled stops and addressed gatherings without prior arrangements. Often, people collected around him after a meeting, and sometimes, they would insist that he visit a particular village or make a stopover at someone’s house. He often yielded to such requests, especially if he had no fixed programme for those few hours.

Did not all this pose a big risk to his life? The young man replied that it was indeed very risky but then so was the work that Sant Longowal had chosen to do, and he felt there was no escaping that work. Did he retain enough security men around him? Had the government provided him with adequate security? The young man replied that Santji had consistently refused government security but the government insisted on sending a whole trail of guards wherever he went. In addition, a few young men from amongst his followers stayed with him night and day, acting as his guards. Why did Santji refuse the security provided by the government? The young man replied in the same soft tones: “Santji does not want to inhibit his movements and restrict his work because of the risk to his life. He wants to remain fully accessible to people and the presence of government security men does come in his way.” And then, without any agitation or bitterness, he went on: “Moreover, who can trust the government? He faces greater danger from them than from anyone else.”

I was reminded of the time when, at the end of April, Sant Longowal paid his first public visit to Delhi after the November riots. Apart from addressing a range of public meetings at Delhi, he made it a point to have a quiet private gathering with individuals and organisations such as PUCL, PUDR and Nagrik Ekta Manch who had played a leading role in organising relief for riot victims or had helped through their writings to expose the real nature of the anti-Sikh violence. He made no fiery political speech at that meeting, but with folded hands, in a very quiet and modest way, expressed his thanks to all those who had helped Sikhs in their time of crisis.

After tea, we both had a bath. The washrooms were at the farthest end of the buildings. There were some men sitting in a group in the corridor, having a quiet conversation. As we walked up and down the corridor, no one gave us more than a casual look. It was not as if any of them was making a deliberate effort to ignore our presence. They took our presence as a matter of factly as if we were part of the regular establishment.

Their ease was puzzling. As we found out later, no woman lived or worked in the gurudwara. Women and men from neighbouring villages did come to the gurudwara to perform sewa, pay homage or to have darshan of Santji. It was unlikely that the gurudwara had many women visitors like us who had not come for a religious purpose. Young women travelling unescorted in rural or even urban areas usually excite a lot of curiosity. Even in places where the presence of unescorted women is not unusual, women are usually subjected to curious stares, and often have to answer a number of personal queries. I remembered the time some years ago, when I, with two women friends of my age, had gone to Varanasi. We went to a sarai looking for a place to stay. These sarais are religious charitable establishments and are supposed to provide subsidized accommodation to pilgrims and other visitors to the holy city. We were given a thorough grilling before the man in charge of the sarai allowed us the use of a room. He questioned us regarding our marital status, asked why we had come unescorted, what time we would return in the evening if he gave us the room, and so on. In this gurudwara, no one had even asked us for our names so far, let alone any questions about our marital status— a question women can scarcely ever avoid in any part of India.

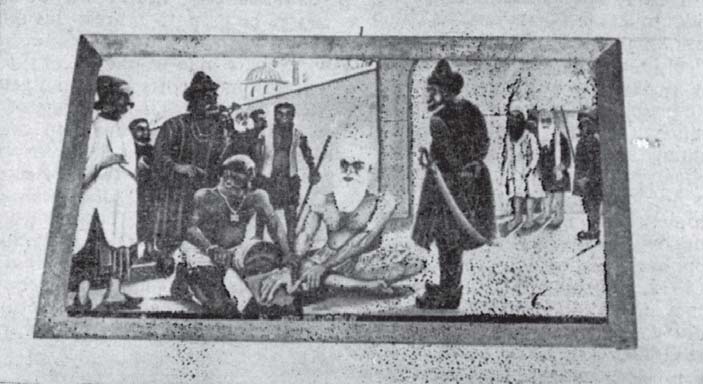

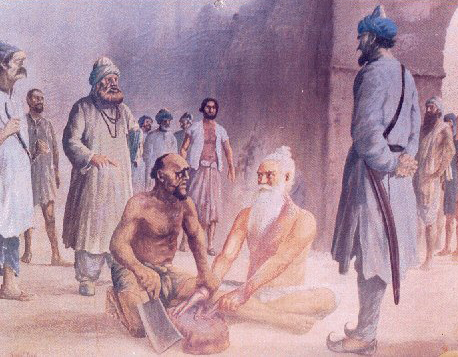

This 1985 vintage black & white photograph of a This 1985 vintage black & white photograph of apainting depicting the martyrdom of Bhai Mani Singh occupied pride of place in the tiny and modest shrine built in Bhai Mani Singh’s memory by Sant Longowal. |

Even more impressive was the fact that we were not asked any questions about our religion. At first, I thought this might be because they assumed that we both must be Sikhs. To dispel any doubts they might have, I made sure to tell my name to the men with whom I talked. Even ordinarily, people are puzzled by my surname. The first name indicates that I am from a Hindu family but the second name comes from a Persian word. So I have often been questioned regarding the combination. But throughout our stay in Longowal gurudwara, neither I nor my friend faced a single query about our religious, communal or political identity.

They treated us like honoured guests even though they had no idea who we were. Even when I said I wanted to interview Sant Longowal no one asked me which newspaper or magazine I represented. Their openheartedness was very surprising, considering the dangers these men were facing.

It was about 4 p.m. by the time we finished bathing. I decided to walk around the temple compound. Not far away from the row of rooms on the left side of the compound was a small room used as the gurudwara. Next to it, stood a beautiful exotic tree of a type I had never seen before.

Under a tree at the other end of the compound, sat a group of elderly men drinking tea which they had prepared on an improvised brick stove. One of them asked me if I would like to have some tea. I accepted the offer and went and sat among them on the string bed. The person who had offered me tea and had answered most of my queries offered to show me around the gurudwara. He told me he was an ex-army man who had travelled widely all over the country during his army days. After retirement, a couple of years ago, he came back to his village which is not far from this gurudwara and decided to devote the rest of his life to the service of the gurudwara as a Sewadar (one who serves). He also told me the story of how this gurudwara came into existence.

It is named after Bhai Mani Singh, said to have died a martyr’s death at the hands of one of the Mughal rulers. The spot of his martyrdom is the site of the present gurudwara which was constructed about 10 years ago. Ever since then, it has also been Sant Longowal’s abode. This place had belonged to a Zamindar and the sthan or location of the holy tree which stands next to the gurudwara was used as pashu sthan or a place to tie animals. The Zamindar donated the land for the building of a gurudwara because of its historical religious significance. My guide told me that just as Bhai Mani Singh stood against the tyrannical power of the central authority at Delhi which tried to subjugate people in different parts of the country, so was Sant Longowal fighting against the authoritarian policies of the centre and its attempts to enslave the states. Few people today remember that Sant Longowal was among the first to oppose the imposition of emergency in 1975. Throughout the emergency, the Akali Dal sent groups of volunteers almost every day from the Golden Temple to court arrest in protest against the repressive policies of the government. It seems Indira Gandhi’s special aversion to the Akalis dates back to this period. The actual gurudwara is a small room about 10 feet by10 feet. The Granth Sahib is kept in the centre of the room and a few oil paintings depicting scenes from Bhai Mani Singh’s life adorn the walls. The room has some shelf space covered by wooden panels. The structure is as plain as possible.

After showing me the gurudwara, the retired army man accompanied me to have a look at the fields surrounding the building. We passed an area where a large room was being constructed. He explained that it would be the room for langar or free meals. Right now, din da prasad or the noonday meal comes from the neighbouring villages and rat da prasad or the night meal is cooked by the Sewadars in the gurudwara. The work is shared by all of them. On the left side, the compound merges with the part of the gurudwara land used for cultivation. This small piece of land is used to grow food for their own consumption. He explained about the different crops grown there, the problems with irrigation and so on. We briefly discussed Punjab politics. He talked about the indiscriminate arrests of innocent people all over the state in the name of curbing terrorism and how even young boys were not spared. He described how men from Punjab were afraid to travel in buses outside their village, especially in Haryana, because anyone could be hauled in by the police or army without even an explanation. There was no anger or bitterness in his tone. His voice remained soft and gentle, and the words he used to express his sentiments were calm and peaceful.

Such a man would be considered exceptionally softspoken and genuinely courteous in any part of the world. But he seemed to merge quietly in the overall atmosphere of the gurudwara. It is not rare to come across gentle, softspoken and openhearted people, but one usually meets them as stray individuals. The unusual thing here was that the whole place had somehow acquired that quality because all those living there seemed to have imbibed it.

The soft tones did not seem the product of rigid discipline. The gentleness was not the artificially acquired quality that one comes across by way of gentlemanliness in some public school products. There were no hushed whispers or secretive silences. They were communicative without being pushy or inquisitive.

Throughout our stay, I did not hear anyone speak in a loud voice for any purpose whatsoever, neither in discussion or other routine forms of communication. For instance, it is fairly common for people in India to give instructions to someone from a distance or call loudly if a person is some way away: “O Banta Singh, go and feed the animals” or “Ram Sharan, where is the axe kept ?” Not once did we hear any of these men shout to another from a distance or speak in agitated tones.

Moreover, we did not see any visible signs of hierarchy or permission asking. This is quite characteristic of most religious institutions. Since there is a long history of Akali politics being plagued by conflicts over control of gurudwaras, the functioning of this gurudwara seemed rather extraordinary. To the end, I could not say who the more senior or powerful personages at the gurudwara were.

Since Sant Longowal bad not yet returned, my friend and I decided to take a walk in the nearby fields. On our way, we saw two young men posted as guards, sitting on a charpai near the outer edge of the gurudwara land. They were smiling as they read aloud from a Punjabi newspaper. I stopped and asked what was making them so happy and smiley. “We were reading an account of Santji’s speech at a public meeting yesterday.” We lingered for a while and continued to talk. They were among the personal bodyguards of Santji, young men in their early twenties, belonging to neighbouring villages, living their life as Sewadars in the gurudwara.

Their shyness and soft-spokenness looked at variance with the weapons they had on their persons. I happened to remark that we had come from Delhi to meet Santji but since we had not made an appointment, I was apprehensive that he might not have time for us. They replied with confidence: “Why won’t he talk to you? Santji never refuses time to anyone who comes to talk to him.”

They spoke of their Santji with the affection, reverence and loyalty usually felt for beloved elderly people in the family, rather than the heads of religious or political organisations. Even though had the alertness required to fulfil their task, they seemed relaxed and cheery and seemed to feel a deep sense of pride in being called upon to protect a man they loved. These and other young Sewadars of the gurudwara seemed to form a magic circle of love and reverence around Sant Longowal. These were men who did not manifest any violent impulses or any great pride in their weapons but seemed ready to risk their lives in the defence of their Santji.

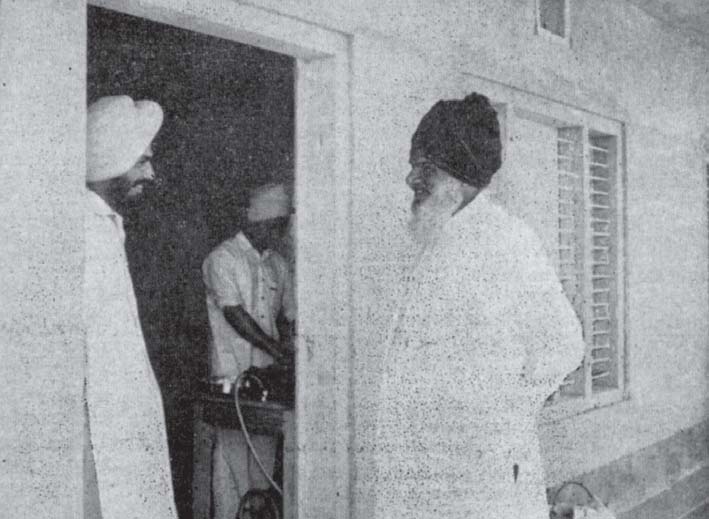

At about 6 p.m, we saw Sant Longowal returning, in a white Fiat car, along with some other men, probably his bodyguards. He was followed by a jeep full of armed police guards provided by the government. Considering that he had been out on dusty village roads since morning in the dry heat of June, he looked remarkably cool and fresh, and his clothes were a spotless white. As soon as he arrived, the various Sewadars slowly gravitated towards his room although no one seemed in a nervous rush or flurry. Within 10 minutes of his arrival, he sent for us in his room. He could not even have had time for a wash or a few minutes of rest because some other people who were also waiting for him were already in his room.

The room he used was no different from others, except that it was smaller and more orderly and neat. It had a wooden diwan like structure which he used as a bed at night and as a seat in the daytime. There were also two plain wooden chairs for visitors, a simple centre table and a small portable room cooler which, we were told, was sent by a wellwisher in Delhi. This room had a small attached bathroom for his personal use. The door to his room was constantly open. I do not remember seeing it closed for 10 minutes. It stayed open until late at night when we went to sleep and was open in the morning when we woke up. People walked in and out without as much as a knock at the door. I did not see anyone asking for permission to enter the room or going through any elaborate greetings ritual. That one small room, neat and orderly, functioned as his bedroom, office and a place for receiving visitors and holding small meetings.

Sant Longowal in his room Sant Longowal in his room |

As we walked in, he greeted us with his eyes and a quiet smile and gestured towards the two chairs to say: “Please be seated.” He waited quietly for us to say what we wanted. My friend introduced herself as the sister of someone known to Sant Longowal. He did not say a word in response but just gave us that steady kindly look which put one at ease in his presence while at the same time discouraging one from taking unnecessary liberties with him. It was surprising that he made no attempt to be more familiar with her because of previous acquaintance with her family. Before reaching Longowal, I had the feeling that I was depending on her to act as a link so that I was not received with mistrust at the gurudwara. But within a few moments of reaching there, I realised how unnecessary that was. Here was a place where no one needed any introduction to prove their credentials. Everyone received pretty much the same treatment. When I introduced myself, he remained similarly benign and detached. I told him I would like to talk to him whenever he was relatively free so that we could talk uninterrupted for a while. He did not ask me what it was I wanted to talk about but merely requested us to give him a little time to attend to the others who had been waiting for him.

His face had a strange half-smile. It could well be mistaken for a complacent look but seemed to me to be a reflection of inner calm.

About an hour later, he called us and sat down to talk to us in the open courtyard, not far from his room. He was as softspoken as all the other men we had met and talked to so far. My own voice sounded unduly agitated to me in contrast to his calm monotone. There was no drama in his voice nor the rhetoric that flows so easily from the tongues of most political leaders. He spoke in measured tones and did not labour to produce any particular effect or impression. The voice stayed at the same pitch and so did his courtesy and temper. I questioned him on a range of issues and he gave simple lucid answers to each question, even to those which must have been thrown at him dozens of times every day. Extracts from my tape-recorded conversation with him, translated from Punjabi, are on page 14. (Part 2 of this article on our website).

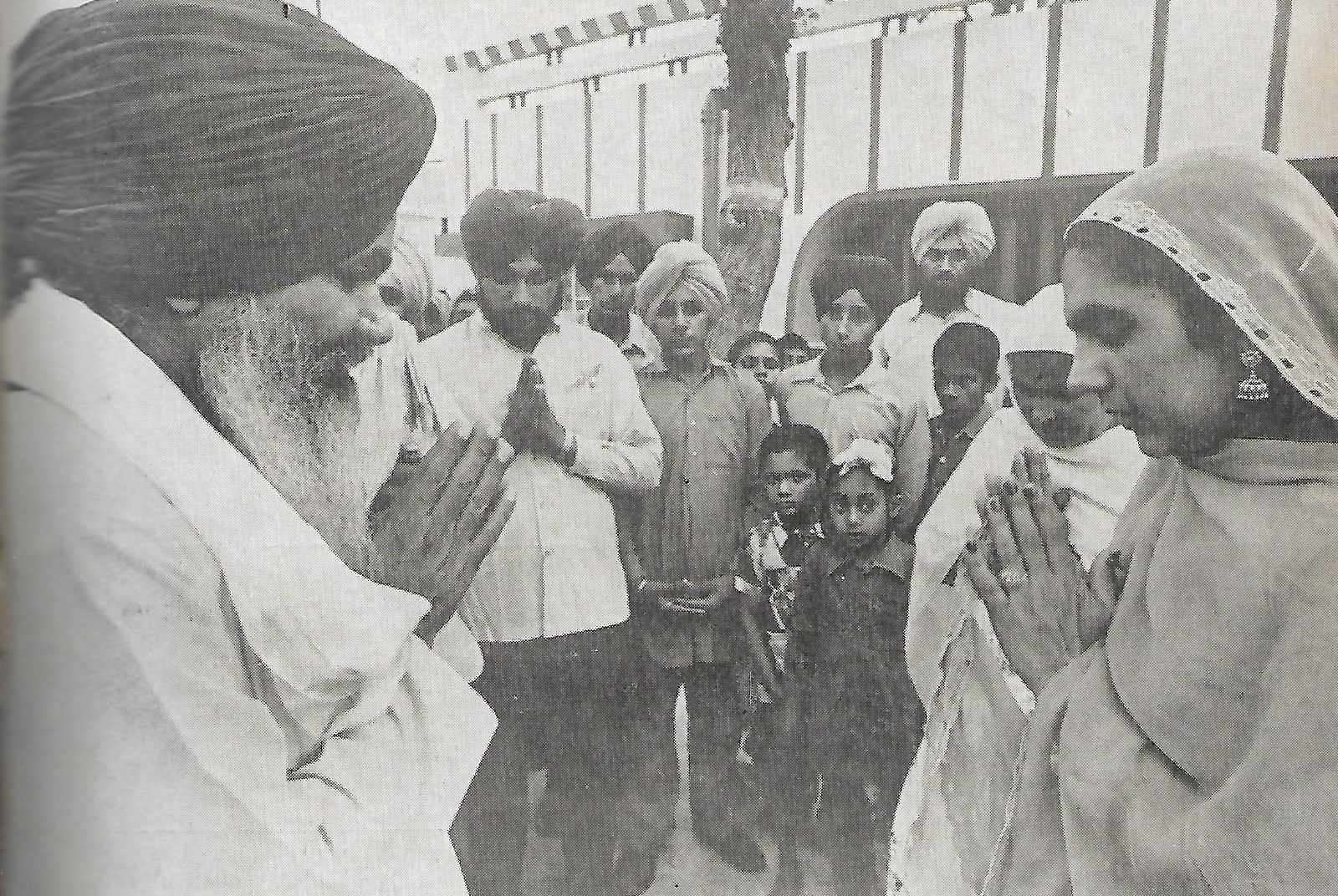

Soon after we began talking, a young man and woman from a neighbouring village walked up to Santji and stood with folded hands. The woman stepped forward and put a ten-rupee note in his lap, folded her hands again and stood quietly looking at him for a few minutes with reverence and love. Santji looked at them, nodded quietly with something resembling a smile on his face, but did not say a word. After a few minutes, they went away as quietly as they had come and Santji resumed his conversation with us. In the meantime, he had gestured to a Sewadar who was walking nearby and handed the note to him. He had not given any blessings to the couple nor had they shown any visible sign of obeisance. Looking on, it struck me that, so far, I had seen him use words only when he had to answer a question or had something definite to say. He did not make any unnecessary conversation.

While we were talking to Sant Longowal, not one of his security guards or members of his staff hung around us. In the beginning, a young man sat some distance from us, but he too quietly moved away after a few minutes. Even though some other people were waiting for Santji, he did not try to rush through or answer abruptly although most of his answers were brief. It was I who cut short the conversation at the end of one and a half hours, realising that he had to attend to other business. He too did not ask me whether I was interviewing him for a particular newspaper or magazine, even though I tape-recorded a substantial part of our conversation. If he had asked me, I would not have known what to say because I had not gone with the intention of recording a formal interview for a newspaper.

The trustful openness in the atmosphere of the place urged me to ask something of him that I had not originally intended. I asked if he would be willing to come and preside over a function which Manushi was planning to hold in honour of Shri Prabhu Dayal who died in November 1984 while trying to rescue three Sikh women who were trapped in a house set on fire by a riotous mob. He agreed without a moment’s hesitation and said he would be happy even to make a special trip for such a mission. (See Manushi No. 29)

He asked if we knew other such cases because he would like to visit the families and offer his gratitude and homage to them. I gave him a copy of Manushi in which we had written about the heroic sacrifice of Shri Prabhu Dayal, and left him to attend to the others who were waiting for him.

Soon after, the two young men who had brought us tea, served us dinner. The food was from the gurudwara langar or community kitchen. It consisted of plain roti, unfried dal and some raw onions. This seemed to be their normal diet. They served us with the tender care one usually associates with women. They stood by the beds out. Before we knew it, they had picked up the beds and taken them outside, assuring us that we would be no disturbance to anyone. We were somewhat uneasy, especially since the place they set the beds was not far away from the place where the men were talking to Santji. Moreover, we also wondered whether the room on the right was Sant Longowal’s room and chatted with us while we ate so that it did not feel as if they were attending upon us.

After dinner, they spread bright coloured cotton sheets for us on the string beds. Sant Longowal was sitting in the courtyard and talking to a group of men, some of whom seemed to have come from neighbouring areas. It was a fairly large group of men but the conversation was a quiet one, conducted in the same soft tones one had gotten used to hearing.

Our beds were inside the room and the room was very hot. We wanted to take the beds out into the open but hesitated to do so because we did not want to disturb their meeting. So we waited for the meeting to finish, and in the meantime, I began to stroll in the corridor. Two of the younger men sensed that we were in need of something and came up to us to find out. We explained that we would like to sleep out in the open but that we could wait for the meeting to conclude before we took men of the gurudwara who slept in the open, might feel uneasy with two strange women sleeping not far away from them. But they were so matter of fact and graceful about our presence that I felt foolish at having gone through the initial hesitancies.

In the morning, we received our glass of tea from the same shy, smiling young man, without our having to ask for it. I wanted to take a few photographs of the place and the gurudwara. Not being in the habit of always wearing a dupatta, I walked into the gurudwara without remembering to cover my head and stayed there for about 25 minutes. No one came to chide me or even politely to remind me to cover my head as is the practice for both men and women when they approach the Granth Sahib. Sant Longowal joined me in the room for a few minutes and explained the history of the gurudwara, but he too seemed wholly unperturbed at my not having covered my head. This lack of dogmatism in not fetishising rituals, made me feel a much greater sense of reverence for the place than I would have if I had been snubbed into displaying reverence through a ritual.

As I was taking the photographs of the place and of the men living and working there, no one asked me why I was taking photographs or what use I would put them to. One young man who was cooking paranthas for our breakfast felt somewhat shy and tried to hide when I approached him with a camera. Some others came around, laughed at his shyness and coaxed him into coming forward for the photograph.

I walked into Sant Longowal’s room and found him listening as one of the staff members translated the write up on Shri Prabhu Dayal in Manushi from English into Punjabi since he read and wrote only in Punjabi. He had ready a letter for Delhi Akali Dal in charge, Sardar Ajaib Singh. This letter explained that he had agreed to attend the function to be organised by Manushi and that we should coordinate and fix a date around June 25. During the course of a brief conversation, he twice reminded me that we must not leave without having prasad or breakfast.

We were to leave by the 9 a.m. bus. My friend went to bath and Sant Longowal saw me waiting for her to finish. He at once insisted that I use the bathroom attached to his room to make sure that we were not delayed. The suggestion was made without any self-consciousness.

Even in normal life, rules of male-female segregation are fairly strict. Religious institutions, especially those that admit only men tend to become even more fetishistic. The naturalness with which the gurudwara people accepted our presence even though normally no women stay there, the total effortlessness behind the courtesy extended to us, the warmth and hospitality and the lack of mistrust in the atmosphere all combined to make that one day a very memorable experience.

Three sewadars of the Gurudwara. The young man inside Three sewadars of the Gurudwara. The young man insideis cooking paranthas for the morning prasad. |

I cannot remember another place in all my travels where I have felt better treated than in that village gurudwara. Even while taking full care of our needs, these men allowed us enough personal space and privacy although the gurudwara represents public space. If we cared to have a conversation, they would stop by and talk but no one pushed himself on us. With such people around, it was not difficult to lose the awareness that we were two women in a strange place, surrounded by men. It was the rare experience of human beings dealing with fellow human beings rather than the tension and conflict that underlie most male-female interactions. And the beauty of it is that these people were not aware of doing something extraordinary.

Before we left, I gave the Sewadars a couple of copies of Manushi. They were not aware of the magazine’s existence and requested that If I wrote anything about Santji, I should send them a clipping. My friend caught a bus back to Delhi but I decided to spend a few more days in Punjab and proceeded towards Jalandhar where I have several friends.

Throughout my stay in Punjab and even afterwards, in Delhi, most people who heard that I had been to visit Sant Longowal at his village gurudwara, reacted with horror, amazement and mistrust. This came as a real shock to me. A typical conversation would go as follows :

“What! You went alone !”

“No, I went with another woman but I could easily have gone alone.”

“You mean you went without police escort ?”

“I didn’t think it was needed.”

“But did you at least inform the police that you were going there ?”

“No. Why should I inform the police before I go to a gurudwara ?”

“But don’t you know they stock arms in gurudwaras? See what Bhindranwale had done in the Golden Temple,”

“But everyone knows that Bhindranwale had been propped up by the Congress (I) to cut at the political base of the Akali Dal in Punjab.”

“That was only in the beginning.

Afterwards, he turned against them and thought be had become a big power by himself.”

“How can Akalis be blamed for that, considering he had been propped up to destroy them ?”

“But he was a Sikh and he did it in the name of Sikhism.”

“He killed as many Sikhs as he did Hindus.”

“Well, did you ask Longowal why they did not try to stop Bhindranwale ?”

“I will if you first get an answer from Congress (I) as to why they propped up such a murder.”

“No, no, you are politicising the issue unnecessarily. They are dangerous people. You should watch out for your safety.”

And that is how most conversations would come to a dead end.

I was surprised to find that this ignorance and prejudice was much more pronounced among educated, urban Hindus than amongst those who are illiterate or live in villages. In the cities of Punjab where Hindus are in a majority, they seem more paranoid than the Hindus living in villages where they constitute a small minority of the population. Communication and interaction amongst Hindus and Sikhs in the villages of Punjab seems fairly easy and spontaneous, while in cities, people are full of mistrust.

Until a generation ago, Hindus and Sikhs were distinguishable only with a certain effort. It was common for one son to be given to the Guru, and to become a Sikh, while another son remained a Hindu. Intermarriages were fairly common. In a matter of a few years, how could they grow so far apart as to know each other only through prejudice and misleading political propaganda?

The reality of my experience of that gurudwara seemed more incomprehensible to many people within Punjab and in Delhi than would have been the case if I had described exploits in some strange distant land. That is why after I came back and repeatedly confronted the same expression of shock and disbelief, I felt compelled to jot down my impressions of that visit, lest after a while I too begin to doubt my own experience, surrounded as we all are by a sea of prejudice. These jottings would probably have remained a private affair, had it not been for the untimely and tragic death of Sant Longowal at the hands of some madmen. I write this in the hope that sharing the tranquillity, kindness and honesty I experienced that day will be of some help in allowing more of us to understand who he was and what he stood for.

| “I have but one mission— to bring back the amity between Hindus and Sikhs. My method is of love.” Sant Longowal said these words to Akali lawyer Gurnam Singh Tir only a few hours before his death. |

An additional reason for my telling the story of my one day stay in that gurudwara is that it helps contradict the stereotyped notions held by most people about the character of Sikhs in general and jat Sikhs in particular, I have myself shared some of those prejudices. People have come to associate them with aggressiveness, a martial tradition, rugged manners, rough tones and behaviour, and blatantly anti-woman attitudes. Yet everything I saw, heard and experienced that day revealed a very different aspect of Sikh life and culture. I am fully aware that was far from a representative gurudwara. Yet it was not as atypical as many people would like to believe it to be.

The assassination of Sant Longowal came as a severe setback to all those people in India who are seeking a peaceful settlement in Punjab. But it did not come as a surprise to anyone who observed the difficult, risky path he had chosen. Not very long ago, he was just another name in Akali politics and was hardly known outside Punjab. Even in Punjab, he was known more as a religious leader as the title Sant implies, rather than a political figure. In less than a year, he emerged as a major political leader and assumed importance for the future of the entire country. He entered the political arena reluctantly and hesitatingly. He was a simple man who did not try to make any grand or dramatic gestures to draw public attention. Yet he has left behind an important political legacy.

The most significant feature of this political legacy lies in the fact that he dared to avow the politics of settlement by fair compromise between the central government and the Sikh community at a time when few people were willing to make such a commitment. He pursued this course in a principled way with rare detachment even though he knew that he was endangering his life by doing so. He knew that the hostility of communalists and statists made the likelihood of political rewards very dim.

Sant Longowal came into prominence in the months after the November 1984 riots when the country was engulfed by a corrosive wave of communalism. The Sikhs felt besieged because of the massacres that took place in many parts of north India after Indira Gandhi’s assassination and also because of the continuing political repression in Punjab following Operation Bluestar. The understandable anger and resentment amongst the Sikhs could well have taken a more disastrous communal turn. Sant Longowal came to play a crucial role by making common cause with those who understood that this was an engineered communal conflict.

From then onwards, he began a virtual crusade, travelling to different parts of Punjab and of the country, explaining that neither the Akalis nor the Sikhs had any real conflict with Hindus and that their real fight was against the ruling party. He made no demagogic speeches but in a quite determined way went on demanding an enquiry into the riots, punishment of the guilty and, at the same time, asserting that he and his party would stand as determinedly against Hindu Sikh violence in Punjab.

This stand did not endear him to all those with a vested interest in strife and bloodshed. He paid for his courage with his life. He was fully aware of the dangers to which his politics exposed him, and also aware that the Akalis had been terribly isolated from potential support throughout the country because of misleading propaganda against them, and could not count on many friends.

His greatest disadvantage lay in the fact that he and his party were held accountable not just for their own actions but also for the actions of their opponents. It has been well reported that Bhindranwale and his crew were propped up by certain Congress (I) factions in order to undercut the Akali political base in Punjab. It is also well known, though not well acknowledged, that a major part of terrorist violence was directed at moderate Akalis in order to terrorise the party into submission. Longowal and his colleagues lived under constant threat of murder at the hands of extremist elements, even before Operation Bluestar.

Yet Longowal and his colleagues seemingly had to answer for the doings of Bhindranwale and his followers. This was not only before Operation Bluestar, when the dividing lines within the Sikh community were not as clearly visible to most people but even after a clear split had taken place and Longowal had not only publicly disowned terrorist politics but also constantly pointed at the Congress (I) link up with it. He had time and again demanded an enquiry into the entire history of terrorist activity in Punjab. It is unfortunate that, except for a few small civil liberties groups, few others, including the major opposition parties, paid any attention to this important demand.

| “No one can browbeat me nor bullets deter me as I am truthful and honest before my Guru. My death would be a small price to pay for bringing sadbhavna (amity) to my brothers and sisters in Punjab.” Sant Longowal said these words to India Today, a day before his death at Kombhowal Gurudwara (India Today September 15, 1985) |

Whatever the other merits or demerits of Akali politics, there is no denying that Longowal and his Akali party suffered because they stood for a more decentralised political system which would involve greater political decision making for the states. They stood for a genuinely federal structure as envisaged by our Constitution. Given the vast diversity of India, most perceptive people acknowledge that this is the only effective way of keeping the country together. But, confronted with a ruling party at the centre which is not only unwilling to allow any meaningful autonomy to the states but is also constantly engaged in installing puppet governments at the state level, this power struggle assumed bloody dimensions for the Sikhs in general and for Akalis in particular. It was in such a time of crisis that Sant Longowal rose above narrow political considerations of electoral power politics and tried to free Akali politics from the dangerous trap into which it had fallen. During this brief period, many people had begun to look on him as a symbol of hope and of more principled politics. In an atmosphere charged with mistrust and hatred, he stood by his religious and political beliefs with rare courage and foresight.

Many avowedly secular politicians view religious leaders with mistrust and see them as representing conservative, right-wing, communal politics. However, religious leaders at certain times have become the force behind powerful, progressive impulses in society. In Punjab, the Congress party, which has always tried to present a secular image, came to play an outright and bloody communal role. This was visible not only during the riots and during the Lok Sabha election but also in the way the conflict over the economic and political demands of the Akalis was manipulated into a Hindu Sikh conflict in Punjab. On the other hand, an avowedly religious leader, Sant Longowal, came to act as an important bridge between the Hindus and Sikhs at the time of their acutest estrangement from each other. He played a crucial role in preventing Sikh politics from falling into the trap of Hindu Sikh confrontation after the November riots when Sikhs were being pushed more and more in that direction. In this effort, he sought for and joined hands with all those who genuinely stood for Hindu Sikh amity.

Sant Longowal’s meteoric rise reveals another important facet of political life in India. He was from a rural background and was trained for religious life. Most politicians, even when they originate from rural areas, tend to gravitate towards cities as they move up in the political hierarchy. They usually maintain only a nominal contact with their own people and their native environment. To the end, Sant Longowal continued to operate from a humble gurudwara in an ordinary village of Punjab. This is one indication that he stayed closely connected with the lives and concerns of ordinary people. He continued to strengthen that contact even though it endangered his life.

For many people, Akali politics is synonymous with bitter factional struggles over the control of gurudwara management boards and terrible infighting over vast financial resources. It is of great significance that most sections of the Akali party chose a man like Sant Longowal to lead them in their hour of crisis. He lived a near ascetic life, had renounced worldly pursuits, owned no wealth or property. He came to represent a unique moral force. He quietly demonstrated the courage to work for peace even when guns were pointed at him. The majority of Sikhs rallied behind him more than they had ever done before for any other leader. It is a sign of the inner vitality of the Sikh community that they grasped the significance of his efforts and lent strength to him in isolating and exposing those Sikhs and Hindus who stood for communal strife and violence.

The manner in which Sant Longowal and his fellow Sewadars run the gurudwara in which they lived also explodes another myth. Cynics often contend that gurudwaras only serve the political purpose of harnessing money resources for the Akalis and hence are basically hotbeds of corruption and power struggle. The gurudwara in Longawal seemed to act as a spiritual repository for people in Punjab. Part of Longowal’s success in mobilising his people for a struggle for peace may well lie in the fact that he could draw on the spiritual resources of his people.

Now that Sant Longowal is dead there is inevitably a sense of despair. An able and courageous leader has gone before he could finish his task. But the outcome of recent elections in Punjab is one indication that he did not die in vain. Yet there is much that needs to be done and can be done by all of us. The Punjab crisis has taught important lessons and we can ignore them only at great cost not just for Sikhs but for all other communities as well.

- Most important is that we should not accept blindly and gullibly all that is told to us by those in power. We should make the effort to seek more accurate information and should not become gullible victims of biased propaganda.

- Communal violence and warfare are not just the creations of bloodthirsty criminals who go around killing in the name of their religion, their nation or some other ideology. Those who passively acquiesce in that ideology of hatred and begin to see Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims as monolithic blocks rather than each as a group consisting of widely differing ordinary human beings no better or worse than any others, also become accomplices in violence and bloodshed. For a long time, Hindus failed to distinguish between a Bhindranwale and a Longowal, merely because both happened to be Sikh. What is worse, people have been taught to justify violence and injustice inflicted on any member of the Sikh community, simply because of the doings of a small number of men who also happen to be Sikhs. If a bomb suspected to be planted by terrorists explodes in Delhi, innocent Sikhs hundreds of miles away from that city begin to fear for their lives. This is a matter of great shame for any society and spells disaster not only for the victim community but for the entire society.

- The Hindus, including those who see themselves as secular-minded, need to do some rethinking in evaluating their role in fomenting communal conflicts. Being the majority community, it is very easy for them to identify their sectarian interests, prejudices and mistrust of other communities as “national” interests. This attitude has contributed to communal tension much more than have the doings of a Bhindranwale. Instead of confronting this reality, many avowedly secular Hindus began to use a Bhindranwale to justify their moving towards more and more anti Sikh or anti-Muslim positions, all in the name of national unity. Such a nation can only be a bloody one and is not likely to be able to stay together.

- Those who focus obsessively on individual acts of violence and terrorism help to obscure our understanding of the more crucial issues around which the conflicts are being waged. Newspapers choose to report on spectacular violent events rather than on the ways that most Sikhs and Hindus in Punjab have actively combated and resisted the spread of terrorism.

- Most acts of terrorism are meant as provocations. If we learn not to be stampeded by them and to base our political reactions on the overall situation rather than on such provocations, these acts of terrorism will not succeed in destroying hopes of reconciliation.

-

Few people today remember that Sant Longowal was

among the first to oppose the imposition of emergency

in 1975. Throughout the emergency, the Akali Dal

sent groups of volunteers almost every day from the

Golden Temple to court arrest in protest against the

repressive policies of the government. It seems

Indira Gandhi’s special aversion to the Akalis dates

back to this period.Sant Longowal and others have tried in their own way to press for the truth about the genesis of terrorist violence in Punjab. He constantly demanded an enquiry into Punjab violence as well as a probe into anti-Sikh riots in north India. The government has conceded a probe into the Delhi riots after great dilly-dallying but even that probe has not made much headway yet. The real story behind the terrorism in Punjab has been told in small bits and pieces through stray newspaper reports but the government has so far successfully resisted any proper enquiry. Small groups of civil liberties activists have tried to undertake the job such as those who prepared the recent Report to The Nation: Oppression in Punjab released by Citizens for Democracy. The way the ruling party and the government reacted to this report indicates that they have a vested interest in not letting the truth be told. We should press for the immediate lifting of the ban on the Citizens For Democracy report, and withdrawal of the charge of sedition levelled against its authors. The willful suppression of such vital information has grave consequences for any society which aspires to function as a democracy. Therefore, we need to put more effort and energy into pressing for a proper investigation and demanding that the information be made openly available. If the government refuses to concede this demand, independent groups of citizens can undertake this job on their however modest their resources.

- Sant Longowal displayed great courage in signing an agreement with the central government in an attempt to end the Punjab crisis. In working for such an agreement, he demonstrated that Hindu Sikh conflict is not inherent in the situation. Once the central government conceded the Akali demands, it strengthened the Akalis in combating elements in both communities who were fomenting communal clashes. Operation Bluestar and the November riots made many in his own community and party mistrustful of Congress government. He knew that they were going to accuse him of selling out to the Congress (I). But he also realised that this was a viable settlement. If the conflict was allowed to go any further, it would surely spell disaster for both Sikhs and Hindus. So even at the risk of being accused as a traitor or having the rug pulled out from under him if Congress (I) backed out, he actively promoted the settlement. He gambled that only thus would there be a possibility that the conflict might become soluble, We need, to ensure that the agreement is honoured and implemented and not allow a small group of hoodlums to sabotage it.

-

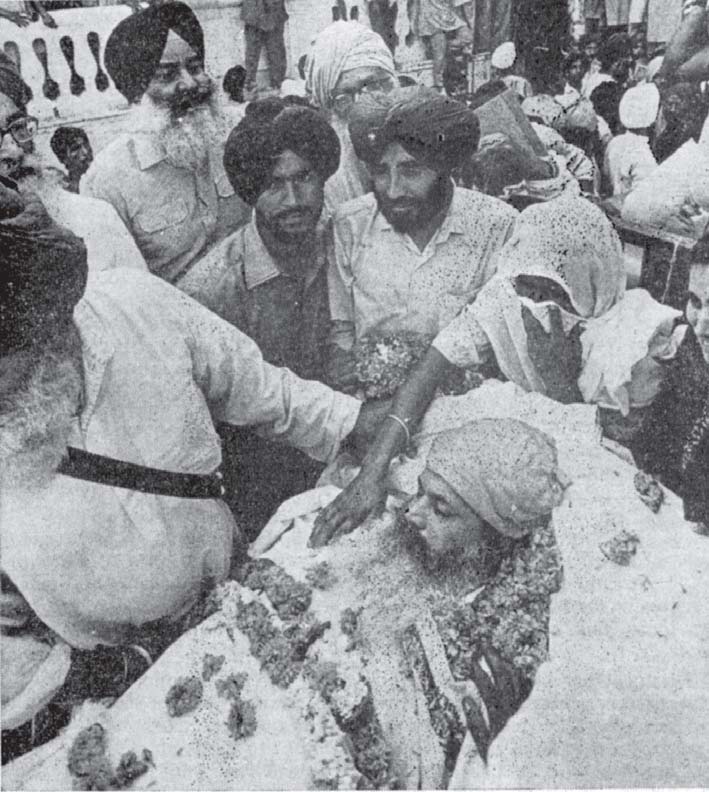

Half the people who joined the

Half the people who joined the

funeral procession of Sant Longowal

were Punjabi HindusThe lesson that has the greatest bearing on India’s contemporary politics is that any attempt to run this country directly from the Delhi throne can only lead to disaster. Indira Gandhi has left a harmful legacy in this regard. She tried to run the country as a private fiefdom, and was extremely intolerant of non-Congress (I) governments in the states, even if they came into power by majority vote. Even with Congress (I) governments, she would handpick chief ministers and tried to instal puppet ministries. In Bengal, Andhra, Kerala, Kashmir, Karnataka, and Punjab, whenever the Congress (I) lost power to opposition parties, she spared no stratagem to throw elected governments out of power, even through blatantly unconstitutional means. The present Punjab crisis owes its genesis to precisely this politics of the centre. The demands of the Akali Dal could have been resolved in a few hours had that been the intention. Instead, she followed a disastrous policy. The Bhindranwale ploy was too more than a product of her politics. The entire country has paid a heavy price for it. We need to become more vigilant against such power games indulged in by our rulers. An important aspect of that vigilance is a struggle to ensure greater local autonomy and a more decentralised politics while ensuring that the interests of the more vulnerable groups at the local level are protected. For example, while we should press for greater autonomy for state governments and protection of Sikh community’s rights as a minority community, we should likewise resist any attempt by some of the Akalis to take away the legal rights of Sikh women by imposing a discriminatory version of personal law.

- Finally, we need to understand that the unity and integrity of the country are not identical to the unity and integrity of centralist state machinery. We can perhaps best safeguard the unity of India by encouraging its diversity to be reflected in popular regional forces being in power in different states rather than press for an artificial unity through an all India party which threatens to impose a highly authoritarian centrist form of government.

The photographs of Sant Longowal were taken by Madhu Kishwar during her two-day visit to his home cum Gurudwara

|

About Shaheed Bhai Mani Singh: Shaheed Bhai Mani Singh (Parmar; Rajput) (1670 – 9 July 1737), assumed control and steered the course of the Sikhs’ destiny at a very critical stage. He compiled Dasam Granth which includes Banis of Guru Gobind Singh.

Bhai Mani Singh was born in village Alipur in Muzaffargarh, Multan. His father, Rao Mai Das Ji, was the son of the great Shaheed Rao Ballu Ji, the General of the sixth Guru Hargobind Sahib’s army. Shaheed Mani Singh Ji Parmar’s family comes from a family of powerful rulers who originated from the legendary Chandarvanshi, Parmar dynasty. He was the 23rd descendent of great legendary Rajput Emperor of India, Vikramaditya. Brutal Killing of Bhai Mani Singh: Bhai Mani Singh was executed in 1737 by the dismemberment of his body parts bit by bit. The reason for this horrific killing? Bhai Mani Singh had asked to Governor of Lahore, Zakaria Khan, for permission to hold the Diwali festival to celebrate Bandi Chhor Divas at the Harmandir Sahib. The permission was granted on condition that a tribute of Rs. 5,000 be paid to the Governor. He hoped that he would be able to pay the sum out of the offerings to be made by devotees of Harmandar Sahib who were going to come in big numbers. The Governor had different intentions. He sent secret orders to his forces to make a surprise attack on the devotees during the festival. Bhai Mani Singh came to know of this plan and sent messages to tell devotees to cancel their visit. The Sikhs that did come had to leave because of the presence of massive military force and suspicious movement of the commanders. Thus no money could be collected or paid to Zakaria Khan. For this “crime” Bhai Mani Singh was ordered to be executed. Bhai Mani Singh was taken to Lahore in chains. Since he could not pay the fine of Rs 5000 he had agreed to pay the Mughals to get permission to celebrate Diwali in Harmandar Sahib, he was ordered to convert to Islam. When he refused to give up his dharma, he was ordered death by dismemberment. When the executioner started to begin with his wrists, Bhai Mani Singh sincerely reminded the executioner of the sentence, reminding the executioner of his punishment and to start at the joints in his hands. When he was just 14 years old, Bhai Mani Singh acted as the scribe to Guru Gobind Singh who dictated to him the Sri Guru Granth Sahib. He also transcribed many copies of the sacred Sikh scriptures which were sent to different preaching centers in India. He was a revered as a scholar, a philosopher and teacher of Gurbani. He complied the Dasam Granth (Book of the Tenth Guru) of Guru Govind Singh. Besides this, Bhai Sahib also authored Japji Sahib Da Garb Ganjni Teeka (teeka means translation and explanation of a work). He expanded the first of Bhai GurDas’s Vaars into a life of Guru Nanak which is called Gyan Ratanawali. Mani Singh wrote another work, the Bhagat Ralanawali, an expansion of Bhai GurDas’s eleventh Vaar, which contains a list of famous Bhagats up to the time of Guru Har Gobind. In his capacity as a Granthi of the Darbar Sahib at Harmandar Sahib, Bhai Singh is also stated to have composed the Ardaas (Supplication) in its current format; he also started the tradition of mentioning deeds of various Gursikhs with the Ardaas |

The description of his martyrdom is a part of the daily Sikh Ardas (prayer).

The description of his martyrdom is a part of the daily Sikh Ardas (prayer).