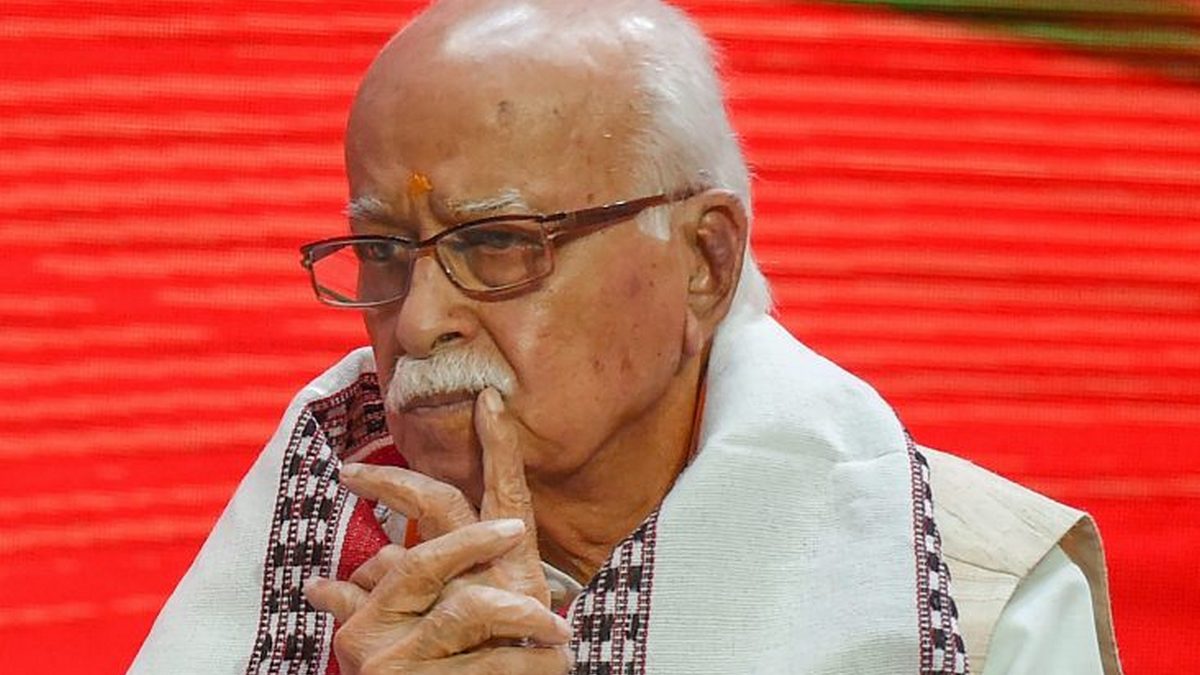

Lal Krishna Advani, the man who shaped the Bharatiya Janata Party in its move from the fringes to become a national party, was forced to quit his presidentship of the BJP under humiliating circumstances—in large part because of a statement he made during his recent visit to Pakistan. One does not know whether to admire or pity him for having refused to withdraw his certification of Jinnah as a “secularist”. He says his aim was to inspire Pakistanis to follow the path of secularism by quoting an extract from Jinnah’s Presidential Address to the Constituent Assembly on Jinnah’s election as its President on August 11, 1947.

With that one speech Advani caused so much outrage within each and every section of his Sangh Parivar, including his die-hard followers and lifelong admirers that friends and foes joined together to oust him from his position. More importantly, he did not win a single friend even among those sections he was aiming to win over with his novel strategy. All hues of “secularists”—Congressmen, socialists, communists, liberals as well as non-party intellectuals—were upset at Advani bestowing secular credentials on the man who forced a bloody and disastrous Partition on the Indian sub-continent. To annoy such a large spectrum of people at one go, without winning over a single friend, demonstrates rare political genius. Yet, Advani remained unrepentant, preferring to surrender his presidentship of the Party that he built through years of toil, rather than disown his characterization of Jinnah during his recent visit to Pakistan.

This major political upset clearly demonstrates that the ghost of Jinnah continues to haunt the entire spectrum of Indian politics. For most Indians, Jinnah’s legacy endures in the form of Pakistan and Bangladesh supported Islamic terrorist attacks in Kashmir and other parts of India, as well as the fiercely authoritarian and jehad-minded military dominated regimes in both Pakistan and Bangladesh.

Secularism Can be Bloody!: The outrage in India against Advani calling Jinnah an emulationworthy “secular” leader is born out of the mistaken belief that using the term “secular” for a public figure amounts to providing a foolproof guarantee that he is a responsible, democratic, and progressive politician. It comes from the naïve assumption that the worst thing a person can do is to mix religion with politics.

We would do well to remember that most of the highly venerated political figures of 20th century have been those who brought the best values of their faith traditions to uplift politics to new moral heights. By contrast, many of those who claimed to be “secular” and , therefore, treated religion with disdain, caused massive genocides and human suffering.

For example, Mahatma Gandhi made it known that his politics and worldview was rooted in the Hindu Sanatan Dharma and the bhakti-sufi tradition. That did not prevent him from being a world historic role model of ethical politics. Abdul Ghaffar Khan derived strength from his unshakeable faith in Islam. That did not prevent him from becoming the most valued colleague of Gandhi in promoting the cause of communal harmony and freedom from colonial rule. Aung Sang Suu Kui and the Dalai Lama make no secret of the fact that they draw inspiration from their Buddhist worldview. Martin Luther King drew his strength from Christianity. Yet, despite the inspiration they all took from their religious ideals, they remain outstanding examples of politics based on compassion and humane values.

It is worth noting that even Marxists and socialists in India have had to deploy the wisdom of men like Kabir, Nanak, Bulleshah and Namdev whenever they decide to spread the message of communal harmony and the “oneness” of all humanity as a counter to Hindutvavadi agenda. All these bhakts and sufis derived their worldview from their deep connection with the Divine, rather than through “secular” education. This is in itself an acknowledgement that on these issues the wisdom of their secular gods such as Marx, Lenin, Mao do not have much impact on people.

This is not to deny that serious problems do arise when politicians decide to “use” select religious symbols and manipulate religious sentiments of people for partisan or personal ends such as mobilizing a religio-ethnic vote bank in order to acquire power.

History is witness to the fact that religion and politics do not make as lethal a mix as do politics and violence. The US is “secular” but that has not prevented it from polarizing global politics on religious lines. It has become the main agent responsible for spreading a virulent version of Islam because of its own history of support to many authoritarian and criminalized regimes and movements in the Islamic world such as the Taliban, in pursuit of its own geo-political interests. Stalin did not use a religious justification while carrying out his genocide among the Soviet Union’s peasantry. He did so in the garb of a “secular” cause, namely, “collectivization” and the uprooting of those he called “kulaks.” Nor did he confine his waves of assassinations and purges to those with religious beliefs. He claimed that he killed people in the name of building a “secular” and “socialist” republic. Yet, he caused far more death and destruction than many of those who make a cocktail of religion and politics.

Indira Gandhi inherited a Party that Mahatma Gandhi consciously built as a historic experiment to evolve inclusive and democratic politics in a multi-ethnic, multi-religious society. Yet from Mrs. Gandhi’s regime onwards, we witnessed numerous riots, pogroms and massacres involving Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs —many of them engineered or instigated at the behest of Congress party politicians. This is not because they were motivated by religious fervour. It was a product of their desperate search for a consolidated vote bank. The law and order machinery of the secular Indian State willingly collaborated in such crimes through various acts of commission and omission. This enduring legacy owes its origin to the example of the British who supported the politics of Jinnah’s Muslim League. The “secularly” minded British lent Jinnah a big helping hand in his encouragement of communal violence, not because they favoured Islam over Hinduism, but because a divided India suited their geo-political ends.

To those who are targeted for violence, it matters little whether those who have come to murder them shout “Allah-O-Akbar” or “Lal Salaam”, or their war cry is “Pakistan Zindabad,” or “Bharat Mata ki Jai” . Violence, whether justified in the name of Hindutva, or “Azadi” as in Kashmir or glorified in the name of class struggle or Khalistan, destroys not only human lives but even the very causes that are touted as justifications for their violence. It is significant that Gandhi chose “truth and non- violence” as his guiding principles, not any ideology or “ism”. He drew his inspiration from the bhakti-sufi faith traditions rather than the ideology of modern day secularism, as defined by the West.

Jinnah’s Murderous Legacy: Jinnah’s legacy has similarities with the Hitlers, Stalins and Milosevics of world history not so much because he mixed religion with politics but rather because his politics led to unprecedented genocides in the Indian sub-continent since he did not hesitate to use terror, crime and violence to achieve his political ends.

It is well known that Jinnah was not religious minded. He merely used certain religious symbols and Islamic slogans to mobilize Muslims against the Hindus as a political force. He sought to mould the political and economic aspirations and fears of his co-religionists into a virulent form of Muslim nationalism to counter Gandhi’s composite nationalism. Since many Muslims were not ready to follow Jinnah, he sought the help of Islam in order to generate a phobic form of religious nationalism to “unite” all Muslims under his banner, and make them act like a homogeneous monolith that would follow his instructions. His aim was “secular” in so far he was only concerned with acquiring political power for himself as the unquestioned leader of the Muslim community. He rejected democracy because a system of representation that gave each citizen one vote—irrespective of religion, caste or gender— would reduce Jinnah’s stature to that of one among many leaders of the Muslim community. He wanted to be an authoritarian “sole spokesman” of the Muslim community. Though claiming to speak on behalf of Muslims, Jinnah did not trust his own people to make sensible choices and was fanatically hostile to all those Muslims who chose to work under the flag of the Indian National Congress, or those who gravitated towards left, socialist politics.

It was primarily because he could not match Gandhi in mass appeal that Jinnah’s Muslim League resorted to “Direct Action” — a euphemism for riots, massacres, murder and rape to browbeat the Congress Party into accepting the Partition. Though claiming to defend the political and economic interests of Muslims of the sub-continent, he callously left behind many more millions of Muslims in India as a mistrusted minority than could be accommodated within the absurd geographical borders of the new ‘Islamic’ state he created for them. Had he abided by democratic, nonviolent methods and abjured the use of murder and mayhem to actualize his political vision, the history of the subcontinent would have been altogether different.

Even those few in India like A.G. Noorani who valiantly defend aspects of Jinnah’s politics do not go beyond making excuses for his adoption of the deadly “two-nation-theory,” viewing his strategy as the consequence of a failure of Gandhi, Nehru and other Congress leaders to give him due weightage. They claim the Congress bruised his ego by trying to mobilize the Muslims over his head. They make a case that for him the demand for Pakistan was only a bargaining plank for greater clout for the Muslim community in India. Presumably, by refusing to take Jinnah’s assertions of discrimination against Muslims seriously, by refusing to negotiate with Jinnah on his terms, the Congress leaders allegedly forced him to translate his bizarre idea of carving out Pakistan from Muslim majority areas of the sub-continent into a reality so that he alone could emerge as the sole spokesman of Muslims. To quote Noorani: “Jinnah was an Indian nationalist who did not believe that nationalism meant turning one’s back on the rights of one’s community… Jinnah lost his balance, abandoned Indian nationalism and inflicted on both his nation and his community harm of lasting consequences. He was of a heroic mould but fell prey to bitterness and the poison that bitterness breeds.”

Even if we grant that some of the fault lay with Gandhi and other Congress leaders in failing to accommodate Jinnah’s political aspirations and style of politics, just how far is a man justified in inciting mass murder because of a bruised ego before he can be counted among the worst monsters of history? The manner in which Jinnah forced a bloody Partition on India, that resulted in the killing of millions, and uprooting many more from their own homes, caused great anguish and anger among the leadership of the Congress. Yet, the entire Party stood its ground by insisting that Muslims would continue staying in India as equal citizens whatever happened in Pakistan. And they stuck to their resolve even after a near total ethnic cleansing of Hindus from the areas declared as Pakistan. This legacy has remained intact despite Pakistan’s continuing attempts to break this resolve by carrying out a proxy war against India through Islamic jehadis with the aim of provoking Hindus into attacking Muslims in India as a retaliatory measure so that India is engulfed in a prolonged civil war. However, barring localized outbreaks of hostility, as happened in Gujarat, the Indian people as a whole have refused to oblige. This steadfastness is what gives Indian democracy a degree of integrity and versatility, despite its numerous flaws and occasional outbreaks of communal riots.

A Strategic Blunder: Few in India would have taken offence if Advani had quoted any of the earlier speeches Jinnah made during the period when he was sincerely battling with Gandhi and others to oppose introducing religious appeals in politics, as he did during the Khilafat movement. At that time Jinnah was raising legitimate concerns and had good reason to challenge Gandhi’s judgment. However, to quote Jinnah’s address to the Constituent Assembly on August 11, 1947, even if meant as a sincere bid to inspire Pakistanis to uphold the values of secularism, shows a tragic lack of judgment on Advani’s part. By the time this speech was delivered millions of people had already been butchered, raped, uprooted from their homes and rendered destitute. Jinnah does not take responsibility for his contributions to this slaughter.

Instead, the new fantasy that Jinnah wanted to peddle in that historic pronouncement goes as follows:

“You are free; you are free to go to your temples, you are free to go to your mosques or to any other place of worship in this state of Pakistan, You may belong to any religion or caste or creed—that has nothing to do with the business of the state…We are starting with this fundamental principle that we are all citizens and equal citizens of one state. Now I think we should keep that in front of us as our ideal and you will find that in course of time Hindus would cease to be Hindus and Muslims would cease to be Muslims, not in the religious sense, because that is the personal faith of each individual, but in the political sense as citizens of the state”.

What moral sense does this pious rhetoric make when his newly created state of Pakistan had already carried out a near-total ethnic cleansing of Hindus in the territory his government controlled? Subsequent events have proved how disastrous Jinnah’s vision was even with regard to the internal health of Muslim communities in Pakistan. The conflicts between Baluchis, Sindhis, Punjabis, Mohajirs and other ethnic groups in Pakistan are today far more intense and deadly than they were in the 1940’s. Despite wiping out Hindus, Sikhs, Christians and Parsis, the Muslims of Pakistan have become more sectarian and intolerant about their Islamic faith than they were 50 or 100 years ago. Islam has assumed dangerously virulent forms today and Pakistan has come to be associated with terror and tyranny, rather than democracy and secularism. These developments are intrinsic to Jinnah’s ideology rather than unintended, unexpected by-products.

During his days of glory, Jinnah came to represent the deadly resolve that Hindus and Muslims are not just two communities but two distinct nationalities with irreconcilable interests that cannot co-exist within the same nation state. His hysterical emphasis on “separateness” that provided the justification for the twonation theory was a gigantic lie. For example, most Indian Muslims are recent converts and share several common interests with non-Muslims of the sub-continent based on language, culture and region. Jinnah’s own family had converted only a generation previously. Yet he behaved as if Muslims belonged to a different species of humanity than Hindus. This ideology has become more pronounced after the creation of Pakistan because the entire might of the Pakistani state works zealously to bolster this ideology.

Therefore, Jinnah’s pious hope that “In course of time, all these angularities of the minority communities, the Hindu community and the Muslim community will vanish. And we will have a solid Pakistani nation”− amounts to ballooning a cloud-cuckoo-land or a pathetic attempt at self-deception. It is clear from statements like these that Jinnah callously disregarded the scale of human suffering caused by his politics despite having unleashed and authored one of the biggest and deadliest genocides in history. When one contrasts Jinnah’s smugness to the manner in which Gandhi responded to the Partition related massacres, one is shocked to witness how Jinnah’s gargantuan ego rendered him so morally blind that he became incapable of remorse even after causing epic scale suffering.

Communities versus Nationalities: World history is replete with examples of how religious groups can co-exist in the same territory with mutual accommodation and even respect as long as they consider themselves as diverse communities with common interests and obligations to live in peace together in the same country. But the moment one or the other declares itself as a separate nationality whose interests are irreconcilable with the others, and adopts force and violence to attain its goals, ethnic cleansing and/or civil war become inevitable.The kind of hate-soaked, Islamic nationalist movement Jinnah built to counter the composite nationalism of the Congress Party could not possibly lead to the emergence of a democratic minded leadership or system of governance in Pakistan. Therefore, it was naïve of Advani to suggest that Jinnah intended Pakistan to be a secular democracy. Democracies flourish under the guidance of leaders who are capable of cultivating and nurturing a culture of tolerance and mutual respect among different groups of people within a political structure that protects the safety and human rights of both the majority and the minorities. Jinnah promoted a politics based on hatred, intolerance and the right of majorities to tyrannize and even wipe out minorities. Pakistan cannot rebuild itself into a healthy democracy without disowning the Jinnah legacy, just as Advani cannot hope to position the BJP as a party of democratic governance as long as dominant sections of the Sangh Parivar believe Hindus alone have the right to decide the form and shape of Indian nationhood.

Advani, a Failed Jinnah: Advani was following in Jinnah’s footsteps when he launched his Ram Mandir campaign. He did not care that his rathyatra left behind a trail of bloodshed and mayhem, as he went about “uniting” Hindus not just to counter what he viewed as a Muslim vote bank, but also to combat the strengthening of backward caste vote banks. Advani appeared to succeed for a while, at least in some states of India. But those hopes came crashing down after the demolition of the Babri Masjid. In the very next elections, the BJP lost power in Uttar Pradesh itself, the bastion of the Sangh Parivar’s Hindutva campaign. A united Hindu vote bank continues to elude the Sangh Parivar even in its strongholds. The BJP became a political untouchable until it temporarily negotiated the National Democratic Alliance that put on the back burner the Hindutva agenda in its manifesto.

Just as Jinnah made the lives of Muslims he left behind in India far more vulnerable than they ever were in undivided India, so also Advani did not care that by demolishing one mosque in India, he legitimized the vandalisaton and demolition of hundreds of remaining Hindu temples in Pakistan and Bangladesh. The already terrorized Hindu minorities in both these Islamic Republics became targets of much greater victimization and attack as a consequence of Hindutva violence in India. With his Jinnah – like “Direct Action” against one mosque, he encouraged Pakistan to help make India the target of many Osama Bin Ladens and Dawood Ibrahims.

The Sangh Parivar hates Jinnah because Jinnah succeeded in his mission of dividing India by “uniting” Muslims into an ethnically cleansed state, whereas a whole century of efforts by the Sangh Parivar to likewise “unite” Hindus have not produced comparable results. They are haunted by the fact that a Muslim leader, despite representing a minority of the sub-continent’s people, could force his will on the entire territory, while Hindus repeatedly snub leaders who develop Jinnah-like aspirations. Advani lost the clout he once had within the Sangh Parivar because he proved to be a failed Jinnah. It ought to be a matter of pride for us that our political and social value system does not allow Jinnahs to flourish beyond a point in India, as demonstrated by the still more pathetic fate of another Jinnah aspirant—Shiv Sena’s Bal Thackeray.