This was first published in the print edition of Manushi journal, Issue No. 48 of 1988

For years now, we have participated in the common refrain that dowry is a social evil. Slogans have been raised against it; politicians have condemned it from public platforms; parliament has legislated against it. We ourselves were caught up enough in the euphoria to have taken a pledge in 1980 not to attend any dowry weddings (see Manushi No.5)

This pledge was prompted by the fact that almost everyone, including those who are at the forefront of antidowry campaigns, continues to give and take dowry. We had hoped that the refusal, even by a few people, to attend dowry weddings, would build pressure within their families and communities against the practice and that the boycott would spread.

However, neither did the pledge have the desired effect, nor did it bear fruit even when taken on a larger scale, in the course of campaigns by other organisations. Very few, even amongst Manushi readers, responded when we gave a call for more signatories to the pledge (see Manushi Nos 7 and 8). Amongst my family, friends and neighbours, my stand was viewed with respect, even appreciation. But it did not lead anyone (except my two brothers) to refrain from taking (or giving) dowry, even though some were apologetic about their compulsions.

All these years, I have adhered to the pledge, even at the cost of annoying many friends and relatives. Simultaneously, however, I have also been forced to reexamine the question, given that most young women, for whose benefit we wish to “abolish” dowry, are not willing to give up dowry. This raises a political and ethical question — do we, as self-appointed social reformers, have the right to promulgate measures for the supposed welfare of any group when that group does not perceive that reform as being in its interest?

Instead of dismissing the refusal of young women to say “no” to dowry, as being a sign of their “low consciousness” or lack of awareness, we would do better to examine why they are not willing to give it up. The answer is simple. Under the existing family structure, giving up dowry does not entail any alternative advantage for a woman. She loses the little she would get and gains literally nothing. And yet, we the social reformers have shied away from this simple answer, and have continued to demand that women, as proof of their “liberated” thinking, should refuse to take dowry.

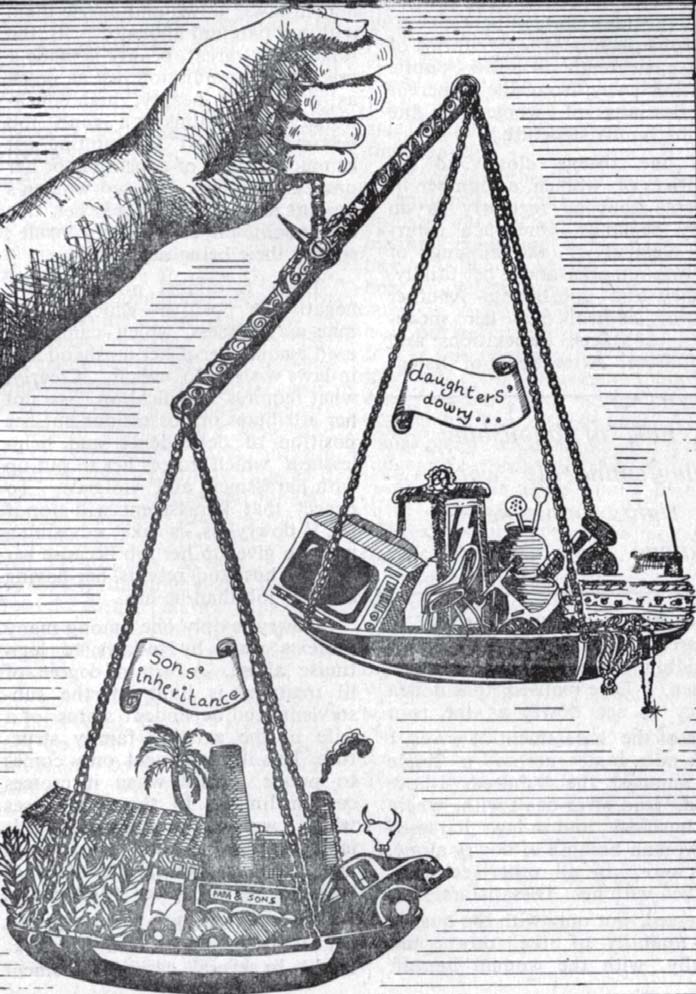

Most women see their dowry as the only share they will get in their parental property. In a situation where women do not have effective inheritance rights, dowry is the only wealth to which they can lay a claim. To suggest that women refuse dowry and go emptyhanded to their marital homes is to suggest that they make even greater martyrs of themselves than society makes of them. Until we can ensure inheritance rights for daughters, we have no right to ask them to sacrifice the inadequate compensation they get by way of dowry.

The few women who, motivated by idealism, do not claim what society recognises to be their due — a dowry — are rarely able to enforce their claim to inheritance rights since society does not recognise this as their due (regardless of what the law may say). Take the example of a colleague of mine, who is the only woman in her family to have built a career and stayed unmarried. She abstained from taking her share of her mother’s jewels when it was offered to her because she does not like wearing jewels. Nor did she get a dowry or its equivalent. The result is that while her brother’s son inherited the ancestral house and business, and her brother’s daughters got huge dowries in cash and kind (much of it of their own selection), she had to start from scratch to build her own assets, and is not sure of where she will live after retirement. Needless to say, no one in the family expects her to demand her share in the family house. If she were to do so, it is likely to lead to a complete rupture with the family. So she ends up staying briefly in what should be equally her house, but is viewed as a semi-dependent of her nephew.

The few women who, motivated by idealism, do not claim what society recognises to be their due — a dowry — are rarely able to enforce their claim to inheritance rights since society does not recognise this as their due (regardless of what the law may say). Take the example of a colleague of mine, who is the only woman in her family to have built a career and stayed unmarried. She abstained from taking her share of her mother’s jewels when it was offered to her because she does not like wearing jewels. Nor did she get a dowry or its equivalent. The result is that while her brother’s son inherited the ancestral house and business, and her brother’s daughters got huge dowries in cash and kind (much of it of their own selection), she had to start from scratch to build her own assets, and is not sure of where she will live after retirement. Needless to say, no one in the family expects her to demand her share in the family house. If she were to do so, it is likely to lead to a complete rupture with the family. So she ends up staying briefly in what should be equally her house, but is viewed as a semi-dependent of her nephew.

While in some cases the woman is not allowed to enjoy her dowry, in many other cases she is able to exercise control, partial or total, over it. To go dowryless is to be deprived of even this chance. Hence, women’s common sense desire for a dowry.

Her wedding is the one occasion when a daughter is specially and much made of. She has, to some extent, the chance to demand and to select clothes and jewels. This is a valuable experience for most girls, given that, in general, a daughter’s desires are much less indulged by parents than a son’s. Further, a woman never knows whether, after marriage, she will be given any money to spend on her own needs or will be provided with clothes or jewellery. We have heard many women complain that for years together, after marriage, they were not given money by their in-laws to buy a new blouse or a pair of slippers, and continued wearing what they had received in dowry or what their parents continued to give them from time to time — part of the extended dowry. In many cases, therefore, dowry is a woman’s lifeline. To ask her to do without it is like asking workers to protest against wage slavery by working for free and abstaining from taking their wages.

What is dowry? The transfer of wealth at the time of marriage. In itself, this is neither good nor evil. In many societies, marriage payments have been made in different forms. The practice of giving the daughter wealth of some kind — in the form of a settlement or a trousseau or family jewels passed on from mother to daughter — has been prevalent in many societies including throughout Europe until very recently. While this system prompted men to look for women with bigger fortunes, there is no evidence that this, in all societies, always led to the woman’s maltreatment. It may even have enhanced her status under certain circumstances.

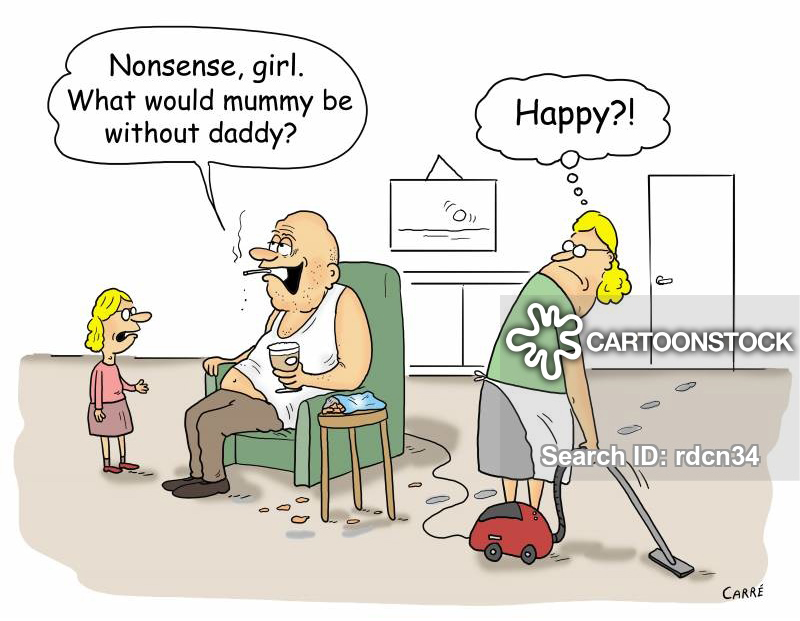

The harassment of wives is related to the utterly dependent and powerless position of women in our present family structure which concentrates economic and decision making power in the hands of men. What we need to fight is not a phoney symbol such as dowry but the power relations within the family. Not giving dowry will not by itself alter the fact that property control is in the hands of men and that women are deprived of it.

The harassment of wives is related to the utterly dependent and powerless position of women in our present family structure which concentrates economic and decision making power in the hands of men. What we need to fight is not a phoney symbol such as dowry but the power relations within the family. Not giving dowry will not by itself alter the fact that property control is in the hands of men and that women are deprived of it.

Social and political activists have tended to single out dowry as the prime cause of maltreatment of wives, and have attributed the increase in dowry demands and payments to growing greed and materialism in our society. In an earlier article, “Dowry-To Ensure Her Happiness Or To Disinherit Her?” I tried to demonstrate how this analysis is extremely misleading and useless in combating dowry. Yet this analysis continues to be popular because it is relatively easier to give sermons to people to be less greedy than to work out ways to actually restructure relations, even within our own families, in a way that power and property control is redistributed.

There is also a widespread tendency amongst activists to confuse the issues by condemning lavish and ostentatious weddings and gift-giving as somehow evil and harmful to women. A critique of waste and ostentation should not be confused with a critique of what goes specifically against women’s interests. The pressure to make a lavish display is not confined to daughters’ weddings, or even to weddings alone. To take just one example, there is great pressure amongst the middle and upper classes in urban areas to make increasingly lavish displays – more recurrent than weddings – on children’s birthdays. Parents do complain even while they comply, but the pressure certainly does not lead them to harass or kill their children. Nor does it act as a deterrent to having children. Therefore, we should take with a pinch of salt the argument that it is only the fear of having to give dowry and arrange ostentatious weddings which makes people prefer sons to daughters, or makes them neglect daughters.

When, in the mid-1970s, it was discovered that many of the deaths of married women which used to pass off as accidents were in fact suicides or wife murders, women’s organisations and the press too quickly assumed that the main cause of these deaths was the greed for dowry. One possible reason why this happened is that when the woman’s parents narrated the story, they always projected dowry demands as the most torturous part of the harassment inflicted by her husband and in-laws.

To the woman’s parents, dowry demands loom the largest because this is the one form of harassment which has to be borne by them. All the other forms of torture have to be borne by the woman alone. If she is taunted for her looks, culinary or housekeeping skills, mannerisms, inability to bear a son or inability to “please” her husband, as almost every woman in such a situation is, the near invariable response of her parents is to tell her to try to improve herself, to “adjust” and “mould” herself to her marital family’s requirements. But when the taunt relates to dowry the woman’s natal family, especially the men, finds itself in the dock. No adjustment on the woman’s part will do -it is her father who has to adjust to the demands for more wealth. That is why this particular aspect of the harassment pinches the woman’s family most, and eclipses all else in their minds.

If the woman is killed or thrown out by her husband, her parents have yet another reason to project dowry demands as the primary or only cause of harassment – they hope to get the dowry back. Even if the woman is alive, it is relatively easier to get part of the dowry back than to ensure that the woman can live with dignity in her inlaws’ home.

When the woman is dead, it is always her parents or brothers who bring the case to public attention; even when she is alive, she is almost invariably accompanied to the police station or the social organisation by her father or brother because she badly needs their support. In most cases, the father or brother is the one to draft the complaint and narrate it to the authorities.

To the woman’s parents, dowry demands loom the largest because this is the one form of harassment which has to be borne by them. All the other forms of torture have to be borne by the woman alone To the woman’s parents, dowry demands loom the largest because this is the one form of harassment which has to be borne by them. All the other forms of torture have to be borne by the woman alone |

In this narrative to the police and the social worker the father, brother or even the woman herself is usually compelled to highlight dowry demands and to downplay other problems because today, dowry demands are perhaps the only form of harassment which will be unequivocally condemned, even by the police. Other forms of harassment, including even wife-beating, are much more likely to be condoned. When told that the husband berates or beats his wife, the police tend to ask “Why does he do so?” implying that she must be provoking him. That, under no circumstances, should a man beat his wife is not yet universally accepted in the way that it is accepted that dowry demands are wrong. So, highlighting dowry demands is one of the simplest ways to get a complaint to be taken seriously and registered as a criminal case. In the process, it comes to be projected as the main cause of harassment. The downplaying of other forms of harassment tends to draw public attention away from the inherent powerlessness of women in the existing family structure.

If one listens closely to the narratives of women, a number of elements recur as regularly as do dowry demands. One such recurrent element is the flinging of insulting remarks about her family, ancestry and upbringing. Another is strict control over her movements, contacts, associations and expenditure. After years of listening to the detailed narratives of harassed wives, and working in providing legal advice to such women, I have realised that it is a fallacy to see dowry as the root cause of the harassment of wives. I have not come across a single case amongst the hundreds I have heard, read of or dealt with, where the husband and in-laws harassed the woman because of dowry alone, and were, in all other respects, satisfied with her. Dissatisfaction is expressed, not only with the quality and quantity of the dowry but equally with the woman herself. She is told that the husband could have got not just a better dowry but also a better wife. Criticising the dowry, like criticising her family, is a way of criticising her, and the package deal that she represents. This is one reason why meeting dowry demands almost never induces husband or in-laws to view with greater favour a woman whom they otherwise view with contempt.

It is highly significant that it is not only when the dowry is considered inadequate that a woman will be harassed; this can happen equally if the dowry is considered large and ostentatious. She may be accused of arrogance, of trying to show her in-laws down and dazzle them with her parental affluence. In the same way, great beauty is made a pretext for humiliation just as much as is lack of beauty; high educational qualifications or a good job become a pretext for taunting just as much as lack of education or her unemployability. If a woman’s parents are loving towards her, this can become an occasion for insult; so can their being neglectful.

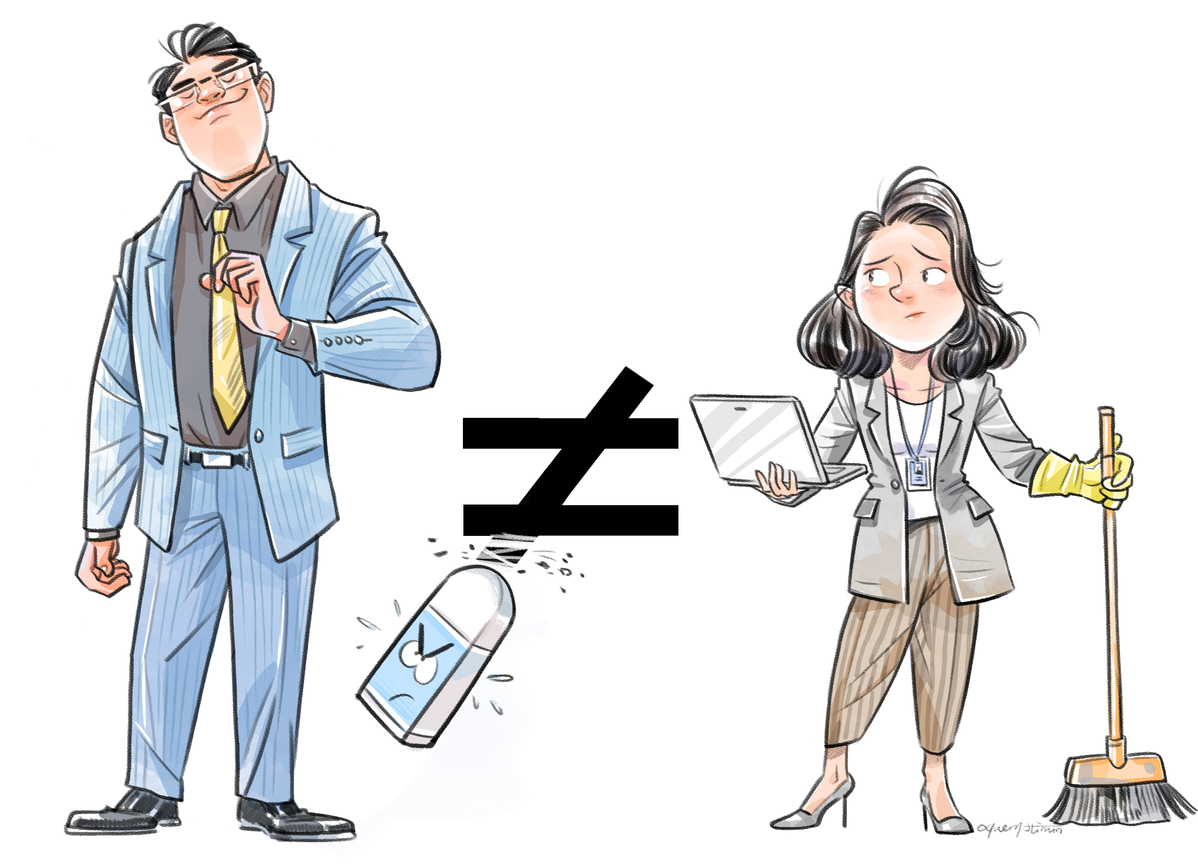

There is almost no attribute — negative or positive — which a woman may possess, which cannot be used against her if her husband and in-laws wish to do so. Clearly, what requires rectification is not her attributes or possessions but her position of dependence and helplessness which forces her to put up with harassment and violence. To expect that harassment will stop if she is dowryless is like advising a wife to give up her job because her violent husband resents her having a better job than he has.

Dowry is only one among many pretexts used by in-laws to legitimise abuse. A certain degree of ill-treatment is built into the subservient and dependent status of a wife in the existing family structure. This ill-treatment only comes to public notice when it crosses certain limits. In those cases where a woman is not illtreated, this is because her in-laws refrain from using their power. But the fact of their having the power still remains.

Dowry in itself does not always under all circumstances lead to blackmail. In several cases, harassment and violence occur without any relation to dowry. In those cases where the woman is in a strong position because of her independent earnings, profession and status in society, and has managed to acquire self-confidence, gifts given by parents, whether or not they are termed dowry, do not make an appreciable difference either way.

Real problem lies not in wealth itself but in who controls it. In our society today, women are not expected to control wealth but to surrender it in favour of brothers or husband Real problem lies not in wealth itself but in who controls it. In our society today, women are not expected to control wealth but to surrender it in favour of brothers or husband |

The real problem lies not in the wealth itself — the furniture or gadgets or vehicles or clothes or jewels, however abundant or expensive — but in who controls them. In our society today, women are not expected to control wealth but to surrender it in favour of brothers or husband. A wife is treated not as an individual who controls her own life and assets but is herself an asset who must perform several functions. One function is to bring wealth just as another function is to provide services of various kinds, and yet another to provide a male heir.

She is usually unable to resist this role because her parents have not treated her differently. Even as unmarried daughters, most girls are made to live a narrowly confined and dependent life. Most parents do not allow daughters to own money or other assets in their own name or to learn to manage the family property. In rural areas, where the overwhelming majority of Indian women live, they may toil on the family farm but are seldom given the right to inherit it as sons are. Even among nonagricultural families and in urban areas, daughters’ education is not taken as seriously as that of sons. Frequently, daughters are actively deterred from taking up paid employment. A life of economic independence tends to be seen as almost a stigma for a woman.

A girl who has been crippled on the pretext of being “sheltered” is not likely to be less helpless just because no dowry is given at her wedding. The well being of such a girl is at the mercy of chance – whether husband and in-laws are good enough to refrain from exercising the arbitrary power they have over her life. If they decide to be nasty, no amount of dowry or lack of it can help her. Most women realise this. That is why they are not convinced by the argument that to refuse dowry would be to ensure their own welfare. They are aware that as their lives are structured today, the chance of getting a kindly disposed husband will play a more important role in their welfare than anything they can do.

If, on the other hand, a woman is equipped to take care of herself and of what belongs to her, her having a dowry will be no disadvantage. If ill-treated, she will know how to resist, how to guard her interests, and how, if necessary, to walk out taking her dowry with her. It is in this context that the recent supreme court judgement defining dowry as stridhan is important. Changing a name would not make a social evil a social good. What the judgement stresses is that shifting control of the assets would render them advantageous to women, whereas today they can be used to her disadvantage.

Today, I find it irrelevant to talk of abolishing dowry. Instead, we should single-mindedly work to ensure effective inheritance rights for women but not on paper alone. We should forget the slogan, ”Dahej mat do, dahej mat lo” ( Do not give the dowry; do not take dowry) and raise the slogan “Betiyon ko virasat do, Betiyan, apni virasat lo.” (Daughters must be given property rights; daughters must claim inheritance rights)

Working to equip women with the resources and abilities to define, control and guard their own interests and their own lives. will make dowry giving irrelevant to their essential wellbeing |

A number of steps need to be taken to facilitate this:

- Any will which disinherits daughters should be considered invalid.

- All land, property and succession related laws, including land ceiling laws, should be amended to ensure equal rights to women, particularly over immoveable property such as housing and land

- Any document whereby a woman surrenders her right in favour of her brothers, husband or in-laws, should be considered invalid.

- A woman should not be able to pass on to her husband or in-laws property inherited from her parents. If she dies childless or under suspicious circumstances, the property should revert to her natal family. This would ensure that her inheritance does not become an incentive for her husband and in-laws to kill her. Her inherited property should be inherited by her adult children or if she is childless and dies a natural death many years after marriage, it may be inherited by her husband, as his would be inherited by her under the same circumstances

If women’s inheritance rights were to become real, dowry in its present form would almost certainly disappear. Gifts at a son’s or daughter’s wedding could not then be at all objectionable, even if termed dowry. Equal inheritance rights would also ensure that a woman who does not marry does not end up emptyhanded.

We should work to equip women with the resources and abilities to define, control and guard their own interests and their own lives. Whether or not they are given dowry will then become irrelevant to their essential wellbeing.

A popular song that indicates the erstwhile prevalence of a dowry system in England, and how “portionless” girls were rejected by suitors:

“Where are you going to, my pretty maid?

I’m going a-milking, sir, she said.

May, I go with you, my pretty maid?

You’re kindly welcome, sir, she said.

What is your father, my pretty maid?

My father’s a farmer, sir she said.

Say will you marry me, my pretty maid.

I thank you kindly, sir, she said.

What is your forture, my pretty maid? My face is my furture, sir, she said.

Then I can’t marry you, my pretty maid.

Nobody asked you, sir, she said.