This was first published in the print edition of Manushi journal, Issue No. 57 of 1990

What the Law Says

Hindu Law:

The majority of India’s people, including all those defined as Hindus, Buddhists, Sikhs and Jains, are governed by what is known as Hindu law. Before the British rulers attempted to codify Hindu law or put it into the form of a parliamentary enactment, communities in different parts of the country were governed by widely differing systems of law, such as the many schools of Mitakshara in different parts of India, the Dayabhaga in Bengal, the Marumakkattayam, Aliyasantana and other kinds of matrilineal law in certain parts of the south. A number of legal treatises including the Smritis and various commentaries on them, ranging from about the second century BC to the eighteenth century AD, were recognised as authoritative in different regions. Local customary practice was also an important factor in determining law. Hindu law was thus a flexible and dynamic set of rules and practices.

Concept of Property: A characteristic feature of Hindu law was the concept of property as owned by an extended family or household. The idea of a birthright is endemic to Hindu law, as to most cultures’ early laws. However, the idea that an individual, by making a will, can decide in advance how property shall be disposed of after his or her death, is a concept unknown to Hindu law.

Every individual had the right to enjoy the property of his or her family, and thus the family was supposed to function as a sort of social security system for the aged, orphans, disabled and others not able to earn. All had the right to live in the family house and to be sustained and educated from the family funds. A child could not be disinherited or deprived of its right to sustenance even by its father. Many early texts lay down in great detail the rights even of those who would in modern terms be called illegitimate children.

While the joint family consisted of both men and women, and all had a right to sustenance, control of property was differently vested in different regions. Under patrilineal systems like the Mitakshara and the Dayabhaga, women, because of the patrilocal nature of the family, were not given a full birthright as sons were.

Under Mitakshara law, joint family property was vested in males in the male line alone. Thus, a man, his sons, grandsons and great-grandsons constituted a coparcenary which meant that each of these males acquired an equal right from birth, even from conception, in the family property. Decisions regarding disposal of family property were to be taken collectively although many powers were vested in the karta or male head of the family who was supposed to administer the property in the interests of all members. Although notionally each male had an equal share in the property, expenditure was not to be apportioned only to males, but the collective good was to be kept in mind. Expenditure on women members’ needs, gifts and endowments for pious and charitable purposes, or expenditure on the special needs of some members, were to be undertaken from the common funds, and no coparcener was entitled to complain that more had been spent on another member than on himself. Females, such as a daughter or a son’s daughter, and males in the female line, such as a daughter’s son, were not part of the Mitakshara coparcenary. Under Dayabhaga law, sons do not become coparceners at birth. They do not have equal rights in family property during their father’s lifetime. However, at his death, they immediately become coparceners.

Under Marumakkattayam law, prevailing in what is now called Kerala, the family was joint and property jointly owned. However, the family was matrilineal and matrilocal. A household consisted of a mother and her children, with joint rights in the property. Lineage was traced through the female line to a common ancestress. Daughters and their children were thus an integral part of the household and of property ownership.

Survivorship and Succession: Under the Mitakshara system, joint family property devolved by survivorship within the coparcenary. This meant that every birth or death of a male altered the share of every surviving male. If a coparcenary consisted of a father and his two sons, each would own one-third of the property. If one of the sons had a son, automatically the share of each male became one fourth.

Mitakshara law also recognises inheritance by succession but only to property separately owned by an individual, male or female. Females are included as heirs to this kind of property by almost all schools of Mitakshara law, but some schools recognise more categories of females than do others. Under the Bengal, Benaras and Mithila schools, only five females can succeed as heirs to a male, namely, his wife, his daughter, his mother, his father’s mother, and his father’s father’s mother. The Madras school recognises, in addition, the son’s daughter, daughter’s daughter, and the sister, as heirs. The Bombay school, which is, in many respects, the most liberal to women, recognises a number of other female heirs, including a half sister, father’s sister, and women married into the family, such as stepmother, son’s widow, brother’s widow, and also many other females classified as bandhus. Some Mitakshara schools allowed a wife to act as a karta in her husband’s absence, while others did not.

Under Dayabhaga law, since the coparcenary comes into existence when a man dies, succession rather than survivorship is the rule. If one of the male heirs died, his heirs, including females such as his wife and daughter, became members of the coparcenary, not in their own right, but representing him. Since females could be coparceners, they could also act as karta, and manage the property on behalf of other members.

Partition under Mitakshara took place when one male member declared his intention to separate and took his share. He and his sons then set up a separate coparcenary. Under Dayabhaga, partition could take place when sons succeeded to the property if they so desired. Under Marumakkattayam law, inheritance was by survivorship. Partition was not allowed. The head of the household was a male, the mother’s brother, or, in his absence, a female.

Stridhan: The concept of stridhan (women’s wealth) or female-owned and inherited property coexists uneasily with the concept of the Mitakshara or Dayabhaga coparcenary and was considered the most complicated part of these laws. It is not known to Marumakkattayam law since there, women were full owners of family property, like men.

Different schools defined stridhan differently. But it usually included any gifts made to a woman by her natal family or by strangers and anything earned by her. Under some schools, it also included gifts made to her by her husband or his relatives.

Just as a male’s separately owned property passed by succession to certain defined heirs whom he could not disinherit, so too, stridhan passed to certain defined heirs. The set of heirs to stridhan was substantially different from that of heirs to a male’s property. This list differed from school to school, but, generally, a woman’s child figured first. In some schools, daughters were preferred to sons, and unmarried daughters to married daughters, this being suggestive of stridhan as a possible hangover from a matrilineal system. The husband and his heirs came next, and the woman’s natal family last. However, most schools laid down that if the stridhan was originally gifted by the woman’s natal family, it reverted to them.

Most Mitakshara schools held that property inherited by succession by a woman from a man did not become stridhan, but reverted to the original owner’s heirs after her death. But the Bombay school held that property inherited by a woman born into the family (daughter) became her stridhan and passed to her heirs, while property inherited by a woman married into the family (widow) was held by her in her lifetime and reverted to the original owner’s heirs on her death.

Limited Estate: Under pure Hindu law, all estate is, in a sense, limited, as the concept of willing away one’s property (absolute estate) is unknown. The property, whether ancestral, descending by survivorship, or separate, descending by succession, whether patrilineal or matrilineal, goes to certain sets of heirs, and it is not in the individual’s power to alter the arrangement and leave the property according to his or her will, or to disinherit anyone he or she may not like.

However, since men were full members of the coparcenary in Mitakshara and Dayabhaga, while women were not, and since men were entitled to act as karta in their own right while women were not, men under these systems had much greater control over family property than did women.

The concept of a will was gradually introduced into Hindu law and this right to make a will was acquired only by men. Under Dayabhaga, men were allowed to make a will in respect of all property, while under Mitakshara, they were allowed to make a will in respect of the separately held property (which generally consisted of self acquired property) but not in respect of ancestral property or of their share in it.

However, when women, as widows, acquired a right over their husband’s share in ancestral property, they continued to have only a limited estate in it. How far they could dispose of it by gift, mortgage or transfer was a subject of much dispute, as was the question of whether women could will away stridhan. Different schools held different opinions on this. The Bombay school held that property inherited by a woman from a woman became her absolute property.

Codification Process: In their attempts to impose countrywide uniformity, first the British rulers and later the nationalist reformers and legislators tried to devise one legal system for all those classified as Hindus, however different their family systems. The process took a long time and proceeded piecemeal by the passing and amendment of several laws. These statutes were based partly on interpretations of certain texts to the neglect of others, and partly on British law. British law was itself undergoing reform throughout the nineteenth century. That it served as a model is clear even from the titles of statutes, for example, the Married Women’s Right to Property Act in England was followed by the Hindu Women’s Right to Property Act in India.

Perhaps the most important new factor introduced by British rule in the shaping of law was that of legal precedent. Decisions of different courts became binding on other courts, and acquired the force of law. The judges often claimed to be guided by the “spirit of the law” or the “reason of the thing” or “general principles”, which were often fine names for their own predilections. A heavy bias in favour of British law and of the northern schools of Mitakshara, is visible throughout the process

The process of codification culminated in the Hindu Succession Act, finally passed in 1956 in a highly watered down form, after over 20 years of fierce debate both inside and outside parliament.

Hindu Succession Act: Provisions:

-

The Act applies to Hindus, Buddhists, Sikhs, Jains and to any other persons who are not Muslims, Christians, Parsis or Jews, unless it is proven that they would not have been governed by Hindu law or custom.

-

Scheduled tribes are excluded from the Act, and are to be governed by their customary law

-

The Act overrides all earlier prevailing laws, rules, texts and customs.

-

When a male Hindu having an interest in a Mitakshara coparcenary property dies, his interest in family property shall devolve by survivorship and not by succession, on the other coparceners.

But if he has any female relative or male relative in the female line specified in class one of the schedule attached to the Act, then his share in the Mitakshara property will be separated, and will devolve by succession on his heirs. The heirs in class one of the schedule are: son, daughter, widow, mother, son of a predeceased son, daughter of a predeceased son, son of a predeceased daughter, daughter of a predeceased daughter, widow of a predeceased son, son of a predeceased son of a predeceased son, daughter of a predeceased son of a predeceased son, widow of a predeceased son of a predeceased son.

(Thus, if a man has two sons, but none of the other above heirs, on his death the two sons will remain coparceners, with half a share each in the coparcenary property. However, if he has a wife, mother, daughter and two sons, then on his death, the property will be divided up into five equal parts, each heir taking one part, unless he makes a will specifying that his two sons are to inherit, or unless his wife and mother sign away their rights in favour of the sons.)

-

However, a man may make a will leaving his interest in coparcenary property to anyone he likes. This is an altogether new provision introduced by the Act, which did not exist according to any earlier text, custom or law.

-

When a Hindu to whom the Marumakkattayam or Nambudri or Aliyasantana law applies dies, his or her interest in the property is separated and descends according to intestate succession on the heirs in class one of the schedule and not by survivorship.

-

The separately owned property of a male Hindu devolves either according to his will or, if he dies without making a will (dies intestate) it devolves first on the heirs in class one of the schedule, and, if there are none, on the heirs in class two of the schedule (father, grandchildren, brother, sister, nephew, niece, grandparents and so on), and if there are none of these either, on relatives through males known as agnates, such as cousins on the male side, and lastly, on relatives through females, known as cognates, such as cousins on the mother’s side; those more closely related being preferred.

-

All property owned by a Hindu woman is her absolute property. The Act abolishes the concept of limited estate. However, a man may in his will create a limited estate, for example, leaving his property to his widow only for her use during her lifetime, or to his daughter only as long as she remains unmarried.

-

The property of a Hindu woman who dies without making a will devolves on a different set of heirs, in the following order, each category inheriting only if no heir in the earlier category exists:

a) her children and husband, taking equal shares. If any child has died earlier, leaving behind children, these grandchildren between them take one share, that of their dead parent.

b) her husband’s heirs.

c) her parents.

d) her father’s heirs.

e) her mother’s heirs.

However, if the property was inherited by her from her parents, and she has no children or grandchildren, the property shall be inherited by her father’s heirs. If the property was inherited by her from her husband or father-in-law, and she has no children or grandchildren, the property will be inherited by her husband’s heirs.

-

In the case of people who were earlier governed by Marumakkattayam or Aliyasantana law, a special provision has been made, in recognition of the matrilineal system under which they lived, that agnates (relatives related through males) shall not be preferred to cognates (those related through females) in the list of heirs to those dying intestate. Further, a woman’s heirs in these communities are the following, each category inheriting only if one does not exist in the earlier category:

-

her children and her mother, taking equal shares, and any children of predeceased children taking between them one share, that of their deceased parent.

-

her father and husband.

-

her mother’s heirs.

-

her father’s heirs.

-

her husband’s heirs

-

Posthumous children have the same rights as other children in inheritance.

-

When a Hindu man or woman dies without making a will, and leaves a house occupied wholly by members of the family, if he or she has both male and female heirs specified in class one of the schedule, then the female heirs have the right to live in the house but do not have the right to demand partition of the house until the male heirs decide to divide it. If they do divide it, each female heir gets her share; if they do not, she does not get a share. But a married daughter has no right to live in the house, unless she is separated, deserted or widowed. This clause does not apply to persons who would have been governed by Marumakkattayam or Aliyasantana law. Women of those communities have a right to demand partition; and married daughters have a right to live in the parental house.

-

Under certain earlier schools of law, persons physically and mentally disabled, suffering from leprosy and certain other diseases, were barred from inheriting property. This Act removes all such bars. Only the following are excluded from the right to inherit: the widow of a predeceased son or grandson or the widow of a brother who has remarried; a person who has murdered the owner of the property to be inherited; children of a person who has converted from Hinduism to another religion.

-

The Act allows any law contravening its provisions to be passed with the purpose of preventing fragmentation of agricultural holdings or of fixing ceilings or for devolution of tenancy rights. As agricultural land is a state subject, the states have passed different laws in these respects.

Limitations: The Hindu Succession Act was framed with two express purposes: to create a uniform codified law for all Hindus; and to give women equal rights in inheritance in accordance with the constitutional guarantee of nondiscrimination between the sexes before the law.

It appears, however, that in the process of the Act’s evolution, the former purpose took precedence over the latter. A uniform law was established, eradicating many other schools of law largely in favour of one particular school of Mitakshara law, but neither were females given equal rights nor were the limited rights conferred on them adequately protected.

By establishing a new right to will away property, the Act gave a new weapon to men to deprive women of the rights they earlier had under certain schools of Hindu law.

The main limitations of the Act so far as women’s rights are concerned, are:

-

The retention of the Mitakshara coparcenary without including females in it means that females do not inherit ancestral property as males do. If a joint family gets divided, each male coparcener takes his share and females get nothing. Only when one of the coparceners dies does the female get a share as his heir. In the case of a brother and a sister in a joint family, on the death of their father, the brother would get his own share in the property and also a share out of his father’s share, whereas the sister would only get a share in her father’s share. This is usually considered the most serious flaw in the Act because most immoveable property in the country is ancestral property.

-

The married daughter has no right to live in her parental house. Even her nephews and grandnephews have a right to live in her parental house, but not she. This is the case even if the house belonged to her mother. This clause clearly discriminates against women

-

The Act allows different states to make laws relating to agricultural land, and does not specify that these laws should not discriminate against females.

-

The Act, while it claims to abolish the limited estate of females and to treat them on par with males, still discriminates in terms of heirs. The heirs of a male’s property and of a female’s property are different. A man’s mother inherits equally with his wife and children, while a woman’s parents inherit only after her husband’s heirs, that is, if she has no in-laws. Thus, even a woman’s self acquired property bought from her own earnings would be inherited by her in-laws in preference to her own parents, while a man’s wife’s parents figure nowhere at all in the list of his heirs. This discrimination is clearly an outcome of the stridhan concept which was part of the patrilineal system wherein a woman was viewed as losing membership of her natal family after marriage. The retention of a woman’s mother as her heir along with her children in communities which were governed by Marumakkattayam law clearly reveals the anomaly, and also shows that Mitakshara law was being treated as the norm by the lawmakers. There is no other reason for the privileging of the male line (agnates) over the female line (cognates) in the list of heirs.

-

The Act allows for the retention of the Mitakshara coparcenary – if there are no female heirs or male heirs in the female line, the coparcenary remains unaffected by the death of male members. However, the Act lays down that the Marumakkattayam and Aliyasantana households are broken up as soon as a member dies, and the property devolves by succession, not survivorship. Thus the Act heavily privileges the Mitakshara patrilineal system over the matrilineal systems. The latter have nearly died out in Kerala today due to a variety of reasons. By introducing the right to make wills, and the concept of partition unknown to Marumakkattayam, and demolishing the principle of survivorship, the Act virtually decrees the dissolution of a system wherein women had better rights, and imposes on them an alien system which puts them at a relative disadvantage – for no other reason except “uniformity”.

-

By far the most far reaching change introduced by the Act was the right of a man to will away his interest in joint family property. The legal right of Hindus to will away property was statutorily conferred by the Indian Succession Act, 1925, which was a law based on British law and passed mainly for the benefit of Britishers in India and Indian Christians. None of its clauses apply to Hindus except those relating to the right to make wills. However, even this Act allows Hindus to will away only self acquired property.

The Father’s Will: Under all systems of Hindu law, women had certain inalienable rights in ancestral property, which differed from one region to another. Widows had a right to live in the dwelling house and generally had a right to manage their husband’s share of the property. Unmarried daughters had a right to live in the house and to be maintained. This was a birthright like the son’s birthright. The only difference was that sons had greater powers of management and disposal. Under Dayabhaga law, widows and daughters could even become coparceners and heads of households. Under Marumakkattayam, property passed in the female line and daughters could not be disinherited. They had full right to live in the house even after marriage, and so did their children.

By giving men the right to make wills, the Hindu Succession Act allows them to disinherit anyone they choose. Given the prevailing bias in favour of sons and against daughters, this power is generally used to disinherit daughters in favour of sons. There are very many cases even of highly educated men disinheriting daughters in favour of brothers’ sons. Thus, all that the Act gives with one hand it takes back with the other. No restriction by way of a safeguard of women’s rights has been laid on men’s power to make wills. A man can give his female heirs only a limited estate in property or can lay down any unreasonable conditions for their enjoyment of property, for example lay down that his widow or son’s widow not remarry. In ancestral property, the Act allows the sons an inalienable share as coparceners; therefore even if the father disinherits them he can disinherit them only from a share in his share of the property. But since daughters are not coparceners they will get no share in ancestral property if the father disinherits them from their share in his share. Thus, the birthright they earlier had is lost. This is particularly injurious in the case of communities that were earlier governed by Marumakkatayam. When the Bill was debated in parliament, the proponents of women’s rights repeatedly pointed out that:

- Either females should be made coparceners on an equal footing with males, or the coparcenery itself should be abolished. The initial pilot of the Bill, Shri Ambedkar, India’s first law minister, had abolished the coparcenary altogether but this met with much opposition in parliament and the Bill was referred to a joint committee which restored the distinction. The retention of two kinds of property – ancestral and self-acquired – puts females at a disadvantage. Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka have recently partially remedied this by making daughters coparceners (see Manushi No. 17), but certain disabilities still remain

- Men should not be allowed to will away ancestral property. Although this was hotly opposed at the time, Shri Pataskar the law minister in whose tenure the bill was finally passed, argued:

“the father is the best man to judge, with respect to his property, as to who should get what… There have been suggestions made that the daughter should be considered as a coparcener… I cannot imagine of a family which can go on smoothly by the addition of a daughter, their heirs and so on”. He even blatantly pointed out that a father could use the will as a means to deny the daughter’s rights: “Supposing the daughter D has been married,… and that daughter is well placed, A can under the new provision… make a will… and provide that she shall have no share in his interest. The joint family will continue as before even after A’s death, without being affected in any way by any of the provisions of this Act. It is thus clear that those who want to be governed only by the existing rules of the Mitakshara system even after the passing of this Act have been given the choice to do so.”

Mr Pataskar’s suggestion was followed by only too many fathers. Some MPs even declared in parliament that they had made wills, disinheriting daughters.

We know today that not only do fathers use wills in a discriminatory manner but that women are generally compelled to sign gift deeds transferring their share both in ancestral and in self acquired property of their parents, to their brothers. Unfortunately, because the power to make wills is undisputed in Western countries whose jurisprudence (particularly British) is the most dominant influence on our own, this right is today no longer the subject of debate but has been accepted as a fait accompli.

Christian Law:

The Indian Succession Act: The Indian Succession Act, 1925, stated to have been passed to consolidate the law relating to testamentary and intestate succession, was intended to apply to Britishers domiciled in India and to Indian Christians. It has special sections on the law applicable to Parsis. It also has sections enabling Hindus to make wills. It was originally to have applied to the property of those married under the Special Marriage Act, 1954, but by a later amendment to the latter, two Hindus marrying under it were to be governed by the Hindu Succession Act and not by the Indian Succession Act. However, the Indian Succession Act applies to two Muslims marrying under the Special Marriage Act, and also to intercommunity marriages under the Special Marriage Act.

The rules of succession applying to a man and a woman are the same.

If a person dies without making a will, the property is divided according to the following rules:

- If there is a spouse and children, the spouse gets one third, and the remaining two thirds is divided equally between the children. If there is only one child, he or she will get two thirds. If fhere are grandchildren but no living children, the grandchildren will divide the two thirds equally between them. If some children are living, and others have died, leaving their children, then the two thirds is divided in such a way that the children of each deceased child divide between them the share of their parent. The same rules apply correspondingly to greatgrandchildren.

- If there is a spouse, but no children, grandchildren, or great greatchildren, the spouse gets half the property and the other half goes to the persons kindred in the following order: father; mother and siblings dividing equally; nephews and nieces shall inherit if their parents have died, on the principle of all of a dead parent’s children together representing him or her; brothers and sisters equally dividing the half of property between them. If there is only a spouse, but no children, parents or siblings, the spouse inherits all; so also, if there is only a mother or only siblings.

- If none of the above relatives are alive, the next of kin inherit according to rules laid down in the Act

Limitations: The most glaring discriminatory provision is that the father is preferred over the mother. If a person is unmarried and childless, and both parents are alive, the father inherits all. If a person has a spouse, but no children and both parents are alive, the spouse gets half and the father half. But if the father is dead, the mother has to share with the brothers and sisters. Under this scheme, a daughter inherits equally with a son. This is the only law in India under which this is the case. Therefore, the law makes no provision for a widow of a son or grandson to inherit the father-in-law’s property. However, the law allows a person to make a will and disinherit anyone he likes. If daughters are disinherited by this means, they will not get any share in the fatherin-law’s property either, if they are widowed.

Parsi Law:

Sections 50 to 56 of the Act deal with the Parsi law of succession. The laws of succession are different for a man and a woman

- If a Parsi male dies without making a will, the widow and each son get a share double that of the daughter. If there is no widow, each son gets a share double that of each daughter. If his parents are alive, the father gets a share equal to half the share of a son and the mother a share equal to half the share of a daughter.

- If a Parsi woman dies without making a will, her widower and children get an equal share of her property. If there is no widower, the children get equal shares. Her parents get nothing if she has children.

- If there is only a spouse but no children or grandchildren, the spouse gets half and the rest is divided among heirs listed in the Act. If there is a spouse and also the widow of a child or grandchild, the former gets one third, and the latter one third, and the rest goes to other heirs. If there is more than one widow of children or grandchildren they divide one third of the property between them.

The remaining part of the property is divided among heirs in a way that each male gets double the share of each equally closely related female. The list of heirs places parents first, next siblings and then paternal relatives before maternal relatives. If there are none of the above relatives, then the next of kin, listed in the schedule, take the property in order of closeness.

The principle of males taking double the share of females who are equally closely related, is followed.

It is evident that this law is clearly discriminatory against women. Even though a daughter is assured a share, she gets only half what a son gets, and this principle is followed with regard to all male and female relatives. Only a woman’s property gets to be equally divided between her children. A man’s parents share along with his wife and children, but a woman’s parents do not.

Muslim Law:

There are five major schools of Muslim law, of which the Hanafi school is followed by a majority of Muslims in India. The five schools were founded by five great jurists: Imam Jaffar, 765 A D, Imam Abu Hanifa, Imam Malik, 795 A D, Imam Shafei, 820 A D, Imam Hanbal, 855 A D. The first is followed by the Shias and the rest by the Sunnis. In India, any Sunni case may be decided in accordance with the opinions of any one of the four jurists.

The Koran and the hadith or traditions of the Prophet, are the chief sources of law, but ijtihad or consensus and local traditions also play a large part in the interpretation of law. There are important and substantial differences in the laws applicable to Muslims in different countries today. In India, its evolution has been greatly influenced by British colonial rule. For example, in pre British times, Wahabis were the most influential sect in India, but since they were also among the leaders of the 1857 revolt, the British persecuted them and deliberately eradicated their influence from the interpretation of law.

Inheritance: A saying ascribed to the Prophet is: “Learn the laws of inheritance, and teach them to the people; for they are one half of useful knowledge.” In pre Islamic Arabia, property passed primarily to male heirs in the male line. These are known as agnatic heirs. The Koran, while sanctioning the right of these heirs, adds 12 more categories of heirs, of whom eight are females. These are known as Koranic heirs. Thus, the prescription that women must be able to read the Koran would ensure not just literacy and religious knowledge, but also knowledge of their Inheritance rights.

We are not here going into all the complexities of the complete system of inheritance which basically operates by ratios. The main heirs under Hanafi law are the spouse, the parents and the children. A husband gets double the share that a wife does; a son double the share of a daughter. The father and mother get equal shares (one sixth) as Koranic heirs, but the father may also inherit as an agnatic heir and would thus get more. These provisions clearly discriminate against females. The principle of representation is not recognised – thus a dead son’s son will not get his father’s share.

Under Shia law, if a man has only daughters and no sons, they inherit more than they would under Sunni law.

Wills: While persons may gift away all their property in their lifetimes, they can only will away a maximum of one third of their property. The rest must be divided among the agnatic and Koranic heirs. A person is of course not required to make a will. In fact, “Muhammadam sentiment is hi most cases opposed to the disposition of property by will” (Asaf A A. Fyzee).

The origin of the permission to Muslims to make wills is a very telling hadis of the Prophet: a man who had a lot of property but only one daughter to inherit it, asked the Prophet if he should bequeath two thirds of it in charity. The prophet said “No.” When asked if half should be bequeathed in charity, he again replied “No.” He then told the man to bequeath one third if he wished to, and added that even one third was “much” for it is better to give one’s heirs security than to leave them in want. Thus, the desire to disinherit the daughter is clearly frowned upon.

Another very important principle of Muslim law is that none of the legal heirs can be given anything in the will. This means that the one third bequeathed can go only to charity or to a friend, but not, for example, to a son.

However, if two Muslims in India marry under the Special Marriage Act, or even, much after their wedding, get their marriage registered under this Act, then the Indian Succession Act will apply to their disposal of property. This means that they will be able to make a will, leaving all their property to anyone they want, for example, to a son, excluding the daughter

The anomalies of the law thus tend to operate in favour of male heirs. Two Hindus marrying under the Special Marriage Act continue to be governed by Hindu succession law, so that their daughters and other female heirs are deprived of the more egalitarian rules of intestate succession under the Indian Succession Act. However, the principle of Muslim law which does not allow a daughter or a wife to be totally disinherited by a father’s will can be evaded by a Muslim father simply by registering his marriage under the Special Marriage Act.

Dower (Mahr): Dower is a sum of money or other property which the husband at the time of the marriage ceremony gives to the wife (known as prompt dower) or promises to pay her on demand (known as deferred dower). It is a settlement on the wife as a token of respect for her. Even if no sum is mentioned in the marriage ceremony, the wife has a right to “proper” dower fixed by the court, which she can claim. Unfortunately, today, the dower fixed is usually a nominal sum. However, if the wife and her family are able to get a substantial sum fixed in the nikahnama she will be legally entitled to it.

When the husband dies, the wife is entitled to claim her dower from his estate, and it is treated as an unpaid debt on par with other unpaid debts which must be paid before the heirs get their shares. The wife gets her dower in addition to her share as a Koranic heir. The dower can be increased at any time by the husband. So the dower is an effective instrument for endowing one’s widow. This means that the widow is the only heir whose share can be increased at will.

In 1956, in the course of the parliamentary debate on the Hindu Succession Bill, Smt Ammu Swaminadhan, MP, arguing in favour of the Bill and of equal inheritance rights for women, said “I would ask the hon. Members to turn to Kerala… If you will only see what is happening and what has happened there all these years when women have had equal right, I am sure that you will agree that… nothing terrible will happen in this country if they had equal rights.”

Yet, many today continue to fear that terrible thing will happen if women actually (not just on paper) get an equal share in inheritance. The arguments put forward against daughters inheriting parental property equally with sons are the same arguments that were put forward over 50 years ago, when the Hindu Succession Bill was first mooted. The Bill, when it finally became law, gave women very unequal rights and even those remained largely on paper. Hence, today, we still need to work for actually getting women equal inheritance rights, as the majority of women in our country, even those of wealthy families, do not own income-generating property independently in their own right, and are disinherited by their fathers for no reason other than their gender.

We shall here attempt to deal with some of the fears commonly expressed regarding women’s inheritance rights.

Land Fragmentation: In India the chief form of income generating property is agricultural land. The Hindu Succession Act, by denying women equal rights in ancestral property, effectively denies them a share in most agricultural land. In addition, the various state administrations have resorted to a number of legal strategems to further obstruct women’s ownership of land.

That giving a share in family land to daughters will result in excessive fragmentation, making each holding uneconomical is a favourite and longstanding argument for denying women a share in this form of property. However, no one argues that giving a share to all the sons will also result in fragmentation. It would be more logical to argue for primogeniture (the eldest child, most frequently, the eldest son, alone inheriting).

Denying women their rights is no answer to the problem of fragmentation, as is evident from the persistence of the problem today, despite such denial. The cause of fragmentation is overpressure on land. A disproportionately large ratio of the Indian population is compelled to depend on land for subsistence. This is a sign of an unbalanced economy. Neglect of agriculture and of rural areas, and draining of agricultural surplus for the benefit of the elite in the urban population, has increased the misery of the land-dependent peasantry.

A part of the answer to this problem lies in implementing honest land reforms, in making agriculture more viable and providing larger sections of the rural poor population with alternative sources of income generation. Denying women a share in land means making them the most powerless section within the already powerless poor peasantry. Certainly, if a piece of land can be divided between three sons, there is no reason why it cannot be divided between two sons and a daughter.

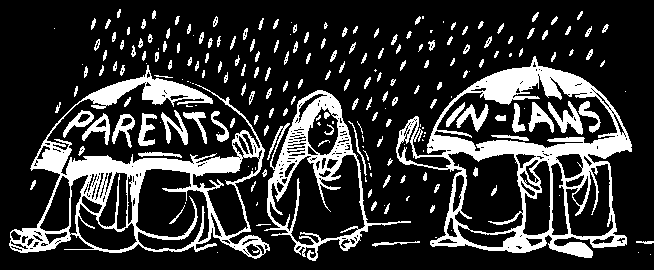

The Daughter Goes Away: Another favourite argument is that since the daughter marries and goes to her husband’s house, which is often far away, she cannot cultivate her parental land, live in her parental house or run her parental business, so these properties should be inherited by her brothers. A subsidiary argument frequently put forward is that since the woman becomes a member of her husband’s family, she should be restricted to inheriting a share of his parental property.

This argument assumes that marriage and going away from the parental home and village are as inevitable as water flowing from a higher to a lower level. But this is not the case. In our own country, many different communities have widely different arrangements. In some tribal communities, where women do most of the land cultivation and where singleness is not despised, a number of women choose to stay single and to remain with their parents, cultivating the land. In several other communities which are matrilineal, married women continue to live in their parental home where their husbands either join them (without being despised as gharjamais as in the north) or visit them.

In many more communities, women are married within the same village or into neighbouring villages. This is the case both in communities where cross-cousin marriage is practised and in some others. Yet, women do not inherit land in these communities and such is the power of ideology that the same argument of women going away continues to be used to deny them equal inheritance rights.

When this argument was used to counter the petition filed by Manushi and two tribal women in the supreme court to demand equal inheritance rights in land for women, our study of a Ho village in Bihar (see Madhu Kishwar, “Toiling Without Rights: Ho Women of Singhbhum,” Economic and Political Weekly, January 17, 24, 31, 1987) showed that of a sample of 22 married women interviewed, seven had married in their own village, six lived less than three hours’ walk away, eight were more than three hours’ walk away. Thus, most of the women were reasonably close to the parental village and land. They routinely cover much longer distances on foot for subsistence activities such as gathering and marketing of forest produce. Yet, as soon as they marry, these tribal women are denied the right to cultivate parental land.

That this is not a reason but a pretext for disinheriting daughters is clear from the fact that however far sons may go from the parental home, they are almost never disinherited on this account. It is as common for sons to migrate from villages to cities, even go abroad in pursuit of employment and career, but they rarely relinquish their claim on parental property. In fact, this claim acts as a bond, encouraging them to visit during vacations, lease out the land or the orchard, claim its produce, even plan to return to the family home after retirement. The claim acts as an important form of security, financial and emotional, for the son. However far away, he continues to be acknowledged as a family member, who must be consulted before property is sold or altered, while a daughter, even in the next village, is treated as a member of another family.

This crucial difference in status is a factor in women’s overall powerlessness in society. It is idle to imagine that a daughter-in-law can be treated as a full member of her marital family with an equal share in its property after she has been totally disinherited by her natal family. The powerlessness of the daughter and of the daughter-in-law are two sides of the same coin. A culture which uproots its daughters and in fact sees this uprooting as the pivot of a woman’s life, which labels a daughter from birth “a stranger’s wealth”, “a migrant bird”, and “a guest” in her father’s house, views its daughters-inlaw at best as bringers of wealth, themselves the wealth of their husbands and parents-in-law (witness the popular slogan Dulhan hi dahej hai -the bride herself is the dowry) but not as an owner of their wealth.

A woman who has full rights in her parents’ property will relate to her husband and in-laws from a position of relative strength. She will have more of a chance to be viewed as an entity in her own right, not as a helpless creature whose only chance of survival and identity lies in “adjusting” to her husband’s and in-laws’ demands and whims Parents who refuse to recognise their own daughter’s full membership in their family and equality with their sons, have no reason to expect that her in-laws, to whom she is a complete stranger, will automatically treat her as an equal inheritor with their sons.

Sons Look After Old Parents: This argument runs: since sons, not daughters, support and look after parents in their old age, sons should inherit the parents’ property.

First, we should note that the implication that sons inherit property as compensation or reward for supporting old parents is not correct. Even if parents die young or in early middle age, when fully self-supporting sons still inherit and daughters do not. Further, many old parents are “supported” by sons from the property or family business that the parents have built up. If the daughters inherited, they could as well support their parents. Significant numbers of women now earn an income and could support their parents. Even women who do not have a job contribute crucially to household income by their work in the fields and the home and should have the right to support their old parents.

A second, very important, dimension of the situation is that since “looking after” old parents is not just a matter of financially supporting them but of serving and nursing them, the actual care is generally provided by the woman, not the man, that is, in our dominant family set-up, by the daughter-in-law, not the son. The daughter-in-law, who is forbidden to care for her own parents, is expected to channel her emotional energy into serving her parents-in-law. Every lapse of hers is noted, more severely than a daughter’s lapse would be. Old parents themselves often acknowledge their need for their daughter, but this need is denied and thwarted. This family set-up, therefore, places strangers in intimate proximity while cutting off from each other those who have been close for years. The resultant frustration, friction and misery, not just for daughters-in-law but also for old parents, is visible in almost every home.

Especially when a very old and ailing mother is in need she is often treated as having no rights in the property, now perceived as her son’s, and is neglected by the daughter-in-law. The present setup conduces not to the welfare of old parents or of women, whether as daughter or daughter-in-law, but to the welfare of adult sons, who virtually take over the parental property in the lifetime of the parents. The culturally unquestioned right of even a misbehaving son over the property of parents he may neglect or maltreat places the old in a powerless situation just as it does women. Indian literature teems with examples of how old parents are sidelined, neglected and allowed no say in matters affecting their own lives and the property they have helped build (see for example, Munshi Premchand’s story “A Mother of Sons” in Manushi No. 42-43,1987).

It will be argued that for married daughters to live with their parents and care for them is “against our culture.” But this assumes that our culture is a monolith. The taboos on eating in, even drinking water in, a married daughter’s home are restricted to certain communities in certain parts of the country, where discrimination against women is most severe. The prevalence of such taboos gives the lie to the argument that the married woman is a member of her husband’s family and should claim property rights there. How can a woman who cannot entertain guests of her choice hope to claim a share in the property of her marital home?

But in many other parts of the country, in most of the south, for instance, such taboos do not obtain. In some communities where it was formerly customary for married daughters to remain in the parental home, there is still a tendency, even after that custom’s demise, for old parents to go and live with their married daughter in her marital home, rather than to live with their son.

If both sons and daughters inherited equally (after parents’death rather than in their lifetime) it would not be as easy for a child simply to take over the parental property and then treat parents as a useless burden. It would also mean that parents could choose to live with the child to whom they feel closest and who they think will look after them best. They could even, as some parents do, live with their children by rotation. The decision regarding which child to live with should not be determined arbitrarily by the child’s gender, but rather by the parents’ and the child’s preference, on the basis of their mutual relationship.

Brother – Sister Love will be Destroyed: Another argument often used against giving daughters property is that it will breed animosity, even litigation, between brothers and sisters, destroying the harmonious and beautiful brother-sister relationship which now obtains.

The flaw in this argument is that it is based on untenable generalisations. Not all brother-sister relationships are beautiful any more than are all brother-brother or sister-sister relationships. Those that are truly so, are unlikely to be disrupted merely because the sister gets her due. If the beauty of the relationship is based solely on inequality, on the brother’s full endowment and the sister’s deprivation, it is a beauty of a questionable kind.

Sisters’ one-way dependence on brothers is occasioned by the powerless and insecure position of those sisters. The status of a woman in her in-laws’ house is affected by how much concern her brothers demonstrate, how often they invite her and how many gifts they give her. These visible demonstrations of concern serve to remind her in-laws that she is not altogether friendless and cannot be maltreated with absolute impunity. A woman cannot call on her married sister’s support as easily, not because sisters care less for one another, but because married women are not usually expected or allowed to shelter or financially help their sisters. A brother, however many his marital problems, does not need his sister’s support in the same way because his survival and well being are not at his wife’s mercy, as the woman’s are at her husband’s. Thus, the brother-sister relationship in many communities is structured by the power of men and the powerlessness of women. It does not make for mutual support but compels the brother to be a perpetual giver and the sister to be a perpetual taker. This is very likely to breed resentments, especially between sisters-in-law. The brother’s wife is forced to forever give, often at her own cost, even from her own dowry, to her husband’s sisters. Such one-way giving cannot conduce to the development of friendship or amity between women. Instead, it sets them up as rivals.

If brothers and sisters inherited equally, better, more equal, relationships could develop between brothers and sisters, and also between sisters, who would be better able to help out one another in times of crises.

Dowry is the Daughter’s Share: This is a red herring which should nevertheless be considered because of its wide prevalence.

Dowry cannot be considered a daughter’s share because:

- it is not in her control as the property is in the son’s control;

- it functions as a bribe to her inlaws to keep her in their house, while property enhances the son’s independent standing; and

- dowry generally consists of extravagant display which enhances family status, and of cash and items which are expendable and do not appreciate in value; while property often comprises income-generating assets such as land, house, tools, machines. Thus, the property provides or enhances a son’s livelihood, while dowry enhances a daughter’s total dependence for survival on marriage and on her husband.

- Dowry often provides an incentive for a man to ill-treat his wife and throw her out of the house. Knowing that she has no culturally sanctioned right to stay in her parents’ house and will be viewed as a burden there, he can demand and extract more and more from her parents as the price for keeping her in his house. The flow of dowry is dependent on her remaining married to him.

Conversely, if she owned certain assets in her own right, and if these assets were legally nontransferable by her, this would be an incentive for the husband to treat her well and keep her in his house. As an owner of the property, she would not be viewed solely as a burden by her brothers either. Knowing that she could go to live in her parental home or even live on her own, the husband would be aware that he shares the use of her property only if she lives with him. Thus, ownership of property would strengthen a woman rather than weaken her as dowry does now.

If equal inheritance by women became the rule rather than the exception, the pattern outlined above would be greatly furthered.

She will Inherit Doubly: It is often objected that a woman will end up getting double rights -inheriting both from her father and from her husband. However, in the natural course of things, as many men would also inherit doubly – from their parents as well as from their wives. Since today in our country men have a longer life expectancy than women, it is even possible that more men outlive their wives than vice versa, though this may be partially offset by the disparity of age at marriage between men and women.

The law should provide that if a woman dies an unnatural death or under suspicious circumstances in her marital home, her property inherited from her parents should revert to her parental family. The husband would inherit only if she died a natural death. The sons and daughters would inherit both parents’ property equally.

Women Cannot Manage Property: It may also be objected that since women in most parts of the country have historically less experience of managing property, and lack the alliances and mobility in the outside world that men have, and also since that women do not have the resources to use violence in defence of property that men have, especially in violence fraught areas of the countryside, effective control of property nominally inherited by a daughter will pass on to her husband and his male kin. It is true that members of any group which has historically been deprived and oppressed will take time to assume full control of any resources they may get. This is true, in different ways, of such groups as Dalits, the landless poor, and women. However, this is not a reason for continuing the deprivation. Rather, putting resources in the hands of oppressed groups is a step towards making the overall culture more egalitarian, and, hopefully, in the long run, less violent.

In the short term, especially as long as women who own resources are isolated individual exceptions, or in pockets surrounded by a culture of women’s deprivation, it may be true that their husbands will wield more control over their property than they will. But even a nominal acknowledgment of the woman’s ownership rights or semicontrol by her will be an improvement over the present situation in which exclusive male ownership is not only the practice but the norm. For example, in matrilineal households in certain communities in Kerala, property was passed from mother to daughter but was often controlled equally or more by the mother’s brother. Yet, women’s status was relatively better in terms of greater autonomy, mobility and better rights in marriage, than in communities where women are disinherited.

We are not, by any means, arguing that inheritance rights are a magic wand which on their own will empower women overnight. But these rights are one important form of empowerment, which, especially if achieved on a sufficiently large scale, could help move the culture in the direction of greater equality and freedom for women.

What about the Propertyless?: Another objection frequently raised is that the entire debate on inheritance rights applies only to the propertied sections of our society.

This is true, but property and assets are not in most cases the equivalent of great wealth. The middle and lower middle classes, the middle and poor peasantry, and even the labouring poor, generally have some assets – a piece of land, a dwelling, trees, animals, implements, a vehicle, a small family trade. Many have a job that can be passed on to a child – also an important resource. The absolutely propertyless or destitute section is significantly large but in the total population, they would be a distinct minority. Further, all those concerned to better the lot of the poor, do wish for and work for the poor to get control over more assets and independent resources such as land and housing. Our government has a policy of giving small groups among the very poor sections of society different kinds of assets – whether in the form of land to the landless, reservations in educational institutions and in jobs to those categorised as scheduled castes and scheduled tribes, housing to slum dwellers, or loans and subsidies, cattle, trees, implements, and vehicles. Too often, the government, influenced by the dominant cultural norms, gives these resources to the male “head” of the family, wrongly assuming that this would take care of the needs of the whole family. In fact, this often further reinforces the inequality between man and woman in the family. Even in reserved categories, there is no special reservation for women.

If we are committed to improving the condition of the poorest and the most oppressed, these are inevitably the women in each oppressed group. Ensuring that they are endowed with assets is also the most likely way of ensuring that the benefits actually reach whole families, as women spend a far larger proportion of their income on the other members of their family than do men.

As more sections of society move in the direction of acquiring assets, they tend to follow the norm set by those sections who already own assets. This trend is visible in the spread of dowry practices from upper caste groups to upwardly mobile lower caste groups, imitating those higher up in the social scale. Thus, changing the norm of inheritance and making it more egalitarian as between men and women is a crucial part of making the whole society and its culture more egalitarian.

Making of Wills: Theoretically, a person making a will is supposed to have complete freedom to leave his or her property to whom he or she wills. In a society where sons and daughters were more or less equally valued, wills would tend to be made fairly equally in favour of both, except when a parent’s relations with a particular child were strained, a consideration not determined by the child’s gender. In our society, however, the cultural assumption that sons are the naturally privileged heirs generally overwhelms all other considerations. Wills are used to disinherit daughters on account of their gender alone, and to keep assets in the hands of men as a group. One has only to look at land records to see how rarely women’s names figure there, or to glance at business establishments’ signboards to notice how frequently “.. & Sons” or “… Brothers” occurs, with the female variant rarely if ever in evidence.

One may compare the situation with that caused by the current misuse of amniocentesis selectively to abort female foetuses. In a society where daughters and sons were more or less equally desired, amniocentesis would present no serious problems; however, in our society it assumes problematic, even threatening, dimensions. So also, with the use of the will as a weapon to disinherit daughters.

It therefore becomes necessary to take certain steps to redress the situation so as to empower women whose present powerlessness has serious adverse consequences for their lives and for society as a whole. It is, for this reason, we would suggest that any will that disinherits daughters in favour of sons should be treated as a legally invalid document. This could be a temporary measure, tried on an experimental basis.

Fears have been expressed by some that in such a situation parents would resort to female infanticide rather than allow daughters to inherit. While it is possible that this may occur as an exceptional aberration, it is unlikely to happen on a wide scale. More likely would be attempts to evade the measure by other means. In any event, in certain regions of the country even today, neglect of female children to the point of death is not unknown, as is evident from the imbalanced sex ratio amongst infants in these regions. Available data from different regions arid countries suggests that infanticide and neglect of female infants are characteristic of those societies where women are disinherited and perceived as a useless burden, while in societies where women inherit and are perceived as full human beings, the proportion of women in the population is significantly larger. The high sex ratio (larger numbers of women to men) in Kerala and in certain parts of the north east is evidence supporting this interpretation. So, trying to right the imbalance in inheritance is one way of trying to change the overall imbalanced man-woman relationship which renders women powerless.

Implementation: While it may not be at all easy to implement such a measure, especially given the failure of our administrative machinery to implement almost any measure successfully, it would be worthwhile for the State to commit itself more unequivocally to the principle of women’s equal inheritance rights. This would involve changing the laws governing inheritance to remove the inequalities contained in them (see grey pages). It would also mean passing laws to render any will that disinherits female heirs in favour of male heirs a legally invalid document, and forbidding the gift or transfer of immovable property by a father in his lifetime to his sons alone; and in the event of a sale, enforcing equal distribution of the proceeds amongst all children. If, however, parents wish to disinherit all children equally in favour of some third unrelated party or a charitable institution, this would be permitted. Property inherited by a married woman should be nontransferable by her.

Even if the measures are not fully implemented at once, they will have some advantages over the present situation:

- A public acknowledgement by the State of its commitment to the principle of equality in inheritance and the need to redress the present highly imbalanced situation. At present, the State machinery actively supports the passing of property from father to son, and the exclusion of female heirs. Even if the State is not able to halt this, it should withdraw its support.

- Individual women who are in a position to demand their rights will be enabled to fight for them, unlike at present when they are disinherited by legal means.

- Just as certain land reform laws endow not just individual landless persons but a whole section of the landless poor with land rights, even though only a few individuals may be able to take advantage of the measure, so also, such measures as outlined above will endow women as a group with certain rights, and throw the weight of the law in their favour, so that if they organise to assert their rights over time, the number of women able to claim their rights may grow.

While it is true that these suggestions are fraught with difficulties and complications, this is one possible way to try and make some change in the present situation of near total disinheritance of women, which causes untold large scale oppression and suffering. In the long run, the full endowment of women will not only improve their lives but also those of men, who will be freed of the anxiety of having to marry off dependent daughters and sisters, and then having to ineffectively intervene when they are maltreated after marriage. We would appreciate further suggestions and a debate on these proposals.

From the Parliamentary Debate on the Hindu Succession Act, in 1956: All of the arguments usually adduced against daughters’ inheritance rights, especially in agricultural land, were raised in the parliamentary debate on the Act. Some members defending the Act cogently countered these arguments, for example: Shri Venkataraman (Tanjore): “… it is urged that we must exclude agricultural lands. Most property in India is agricultural land. It is another way of refusing inheritance to women. If we say so, that would be more honest….Instead of that, you may say that you allow them to inherit water, air, and some natural resources!” Shri B.C. Das (Ganjam South): “… the law which is enacted to stop fragmentation of land should apply to sons as well as daughters….If you say that it will apply only in the case of daughters, that is not right. It is axiomatic that those who are economically independent are really independent…. If the wife comes to the husband’s house as the heir of some property she can claim some respect from the husband. She is an economic entity and she is entitled to claim some respect. That is the reason why the daughter should inherit the property of the father.”

Tribal Law: In most parts of the country, what is known as the customary law of tribal people (who form seven percent of India’s population and who belong to different religions, some being animists and ancestor worshippers), is very close to Hindu uncodified law. Property, which is now mainly land since most tribals have settled down as cultivators, passes from father to sons in the male line. There are matrilineal tribes in the north east, however. In the patrilineal tribes, women are excluded from inheritance. An unmarried daughter has a right to sustain herself from her father’s land. A married daughter, however, loses this right and does not regain it even if divorced or widowed. A widow is supposed to have a right to sustain herself from her husband’s land, but if she has no sons, she is usually pushed out by her husband’s brothers, nephews and other male kin who are the heirs. If she has adult sons, she may be somewhat better protected. The injustice of this denial of rights to women is particularly apparent in tribal communities since women do about 80 percent of the agricultural and related work, including gathering forest produce, marketing, and cultivation. They are the mainstays of the family and the economy. Yet, they have no independent foothold on either the father’s or the husband’s land, and this makes them vulnerable to abuse and violence including such violence as witch hunting which is often used by men to get rid of a single woman or widow whom they perceive as obstructing their rights to the land. Manushi in 1982 filed a petition in the supreme court, along with two tribal women from Bihar, challenging the denial of land rights to Ho tribal women of Bihar, and by implication, to other tribal women (see Manushi No. 13,1982). The petition is still pending in court.