This article was first published in Manushi Issue no-39 of 1987.

This is an account of Manushi’s attempts to organise a meeting for communal amity on June 25, 1985. It may provide some notion of the enormous obstacles all of us face in promoting community-based politics. It also shows how the power structures at the local level tend to thwart any spontaneous political initiatives, no matter how noncontroversial. Even to accomplish small things at the grassroots level, people have to put in a disproportionately huge effort and take big political risks. Most people give up in despair even before things have gotten underway. That perhaps explains why there are so few political efforts at the neighbourhood/community level, and why even fewer survive.

The meeting we organised was not a political meeting in the strict sense of the word. It was meant to pay homage to the memory of Shri Prabhu Dayal, who had died while trying to save three Sikh women from a burning house in Ashok Vihar during the anti-Sikh riots of November 1984. Shri Prabhu Dayal was a resident of Baljit Nagar. He worked in a factory owned by a Sikh family in Ashok Vihar. The employer’s residence was situated on the first floor of the same building. On November 1, 1984, he was in his workplace when a big mob came to set the place on fire. Prabhu Dayal tried to dissuade them from setting the place on fire. However, the mob persisted. Everyone, including the chowkidars hired to guard the place, ran away on seeing the mob. But Prabhu Dayal stayed on and went to rescue three Sikh women who had been trapped on the first floor after the house was set on fire. He sustained serious injuries in the process. He died on November 8, 1984, as a result of those injuries.

We publicised the case through Manushi and decided to raise some funds for Shri Prabhu Dayal’s family. We did this not only because the family needed financial support but even more as a tribute to his memory. We decided that we would present the fund to his wife and children in a public meeting, and invited Sant Longowal to preside over the meeting and join in honouring Shri Prabhu Dayal through his family. I had met Sant Longowal in his village-based gurudwara in Punjab. He expressed eagerness to come to Delhi for this occasion. On June 20, we were able to finalise June 25 as the date on which the meeting was to be held.

The decision to invite Sant Longowal was taken because he seemed to be one of the few leaders who kept emphasising the need for Hindu-Sikh amity at a time when very few people were in a mood for communal harmony. He seemed to be working against heavy odds among both Sikhs and Hindus. We felt that the honouring of Shri Prabhu Dayal — a Hindu — by Sant Longowal would be an appropriate way of emphasising that it is actions like those of Shri Prabhu Dayal which help create a feeling of solidarity between different communities, rather than the doings of those who seek to “unite the nation” by force and violence or through the power of the army and police.

Rulers of nations have a long-established tradition of honouring soldiers who come back victorious from battle after killing others and also who died in battle while trying to kill others. Thus, violence inflicted on others gets to be glorified as heroic. This has contributed to a situation whereby the very survival of humanity is today at peril. Therefore, it has become all the more imperative to ask: what is real courage? To kill other human beings as proof of one’s power, or to choose to place oneself at risk, as Shri Prabhu Dayal did, in order to save the lives of others? In honouring the memory of Prabhu Dayal, we wished to pay tribute to all those who cherish and seek to preserve human life and humane values in the face of the forces which are spreading hatred, enmity and fear between different communities.

We were keen to hold the meeting in the mohalla in which Manushi’s office is situated. We felt that if we held the meeting in one of the public halls which are normally used for political meetings, only politically committed people would attend. By holding the meeting in an ordinary neighbourhood, we would ensure that a number of ordinary people who normally remain outside the purview of struggles for democratic rights, would have easy access to the meeting.

Positive Response: For this reason, we tried to enlist the support of the local residents’ association of our block. We began by talking to the secretary of the association, who happened to be a Hindu. His response was heartening. This was the evening of June 20. Within an hour he introduced us to some other members of the association who also felt equally enthusiastic at the idea.

Next, we went to meet the president of the association, an influential Sikh gentleman of the mohalla, who supported the idea vigorously. These people volunteered to raise funds and take full responsibility for organising the meeting. The cause appealed to Hindus and Sikhs alike. They felt it would generate a better atmosphere in the area. So far, the issue was being discussed with individuals who were not acting as organisational representatives.

| “The drama that unfolded itself taught us that pious statements made by governmental heads on public platforms seldom reflect political reality at the local level”

|

Some members suggested that an extraordinary meeting of the residents’ association be called next morning to finalise the plans. Within a short time, the committed members had been informed. Then began what slowly turned into a traumatic learning experience about the problems of community-based politics. We were naive enough to believe that if Sant Longowal was coming to pay tribute to the memory of a Hindu, and emphasised the need for Hindu Sikh amity, no one, including his worst enemies among the Hindus or in the ruling party, could possibly have any objection to such an event. We were also given to believe that the Centre was in the process of reformulating its attitudes and might adopt a more conciliatory approach to the Sikhs than had hitherto been the case. However, the drama that unfolded itself taught us that pious statements that national leaders and governmental heads make on public platforms seldom reflect the nitty-gritty of political reality at the local level.

At the very outset, two local Congress(I) men began to raise objections to the idea of the residents’ association getting involved in organising or assisting the organisation of a meeting to which a “political” leader had been invited. Many of the members tried to reason that this was not a political meeting. But the Congress(I) men remained adamant and reminded them that the executive committee of the association had decided in one of its meetings not to invite any political leaders for its functions.

At this point, some of the residents began to waver. Yet the overwhelming feeling remained in favour of holding the meeting, and within a few minutes, substantial donations were given by leading residents of the mohalla.

I was the first one to concede the point raised by the Congress(I) men and suggested that in the interest of working by consensus rather than confrontation, we would give up the idea of having the association officially involved in sponsoring the meeting. We were keen to avoid any clashes within the mohalla because that would defeat the very purpose of the meeting.

Despite this initial problem, the enthusiasm remained high. It was decided that even if the residents’ association was not officially involved, individual members could take part and some of them volunteered collectively to bear the entire cost of the meeting.

Whipping Up Hysteria: Soon after this, the local Congress workers began hectic political activity. At no point did they openly oppose the holding of the meeting. But the manner in which they began to sabotage it was far worse than outright opposition. Within no time, an atmosphere of terror prevailed in the mohalla as though a riot was just around the corner. The game they played was masterly and effective. To the Hindus, they said: “You know how hotheaded these Sikhs are. As soon as you allow a meeting like this to be held, the extremists will descend here with their swords and they will deliberately provoke a clash with the police. Once that happens, no one can prevent a riot from breaking out in this neighbourhood.”

To the Sikhs, the message took the form of a barely veiled threat. They were asked: “Can you take responsibility for the behaviour of all the Sikhs who are likely to come here and start shouting pro-Khalistan slogans? Who is going to prevent Hindus from retaliating? If any violence occurs, all of you Sikhs will be held responsible for provoking an attack.” The Sikhs were reminded of the November riots and were told that they ought to be grateful for having been spared during that time. This Lajpat Nagar area had successfully managed to protect itself from attacks, thanks to the joint vigilance efforts of Hindus and Sikhs during the riots. The local Congress(I) leaders took credit for having “saved” the mohalla at that time and darkly hinted that their services would not be available in case “something” happened now.

Since it is well known that the November violence was instigated and organised by the Congress Party with support and patronage from the top layers of the Party hierarchy and active connivance of the government machinery, the idea of displeasing the Congress(I) men created absolute panic in the neighbourhood. Even though many of the Hindus are not consciously aware of it, the knowledge of what happened to the Sikhs during the riots has driven home a very fearful lesson in everyone’s mind. “If Sikhs could be dealt with as they were, why not anyone else or any other group?”

As a result of this fear campaign, another meeting was called the next morning in which a Congress(I) man suggested that we shift the venue of the meeting from the local park in our own block to a large public park in Jangpura. I explained we had already applied to the local police for permission to hold a meeting in our own mohalla park so a shift could create problems. However, sensing the general mood of fear and uneasiness, we agreed that we would try to get police permission for the other park and, if the police permitted it, we would shift the venue of the meeting.

The local Congress(I) man offered to accompany us to the police station and help get the requisite permission. But we were uneasy that going to a large public park away from our own neighbourhood might make the meeting unmanageable. We only had a small number of volunteers and there was no time to mobilise a larger group to ensure order because the meeting was only four days away.

We were surprised to find that throughout this period the constant effort of the two Congress(I) men was to try and get the meeting somehow shifted out of the mohalla. They kept saying: “Why don’t you hold the meeting in Sapru House or some such central place?” and tried to argue that it would then become a big “national” event rather than a small neighbourhood affair, and we would get better newspaper publicity. We told them that was not our intention because we felt that efforts at Hindu Sikh amity should come closer to people’s lives rather than become pious sounding newspaper reports.

Mounting Pressures: When we went to the person in charge of the local police station, we found that the letter asking for permission had not even been forwarded to him so that if we had waited for the permission to come to us in the routine course of things, we would have waited in vain. We did not realise that one needs the right kind of string-pulling even for a routine thing like this. The person in charge of the police station told us that they would need to send their intelligence men to find out whether such a meeting was feasible. He said that, ultimately, permission would have to be granted by the superintendent of police of the area. So off we went to meet him. He was not available so we left another copy of the application and waited for the result.

Within no time we started receiving very aggressive sounding phone calls from men who claimed to be local constables, enquiring why we wanted to hold such meetings which would disturb the law and order situation in the area. One of the phone callers sounded almost threatening when he echoed the Congress(I) men’s words: “Are you prepared to take the responsibility if a riot breaks out?” I reminded him it was the job of the police to make sure that no disturbance took place in our attempt to hold a peaceful meeting. His reply was ominous: “You call a man like Longowal and then try to convince me you do not want to provoke violence?”

In the meantime, the pressure in the mohalla had mounted. Every few hours, there would be a fresh round of meetings, sometimes in this or that one’s house and sometimes, in the park. With three days left for the meeting, we did not know where the meeting would be allowed to be held. How were we to inform people about the meeting? We had planned to print posters and stick them in the neighbouring areas but with all this confusion about the venue, we could not do so.

On the 22nd, we were informed by the police that under no circumstances would we be allowed to hold a meeting in the Jangupra park, ostensibly because of its proximity to Bhogal which was considered a “sensitive” area. We decided to go and see the commissioner of police. He was also of the opinion that Jangpura was unsuitable because during the riots there were severe clashes in that area and even after police arrests of Sikhs, Hindu-Sikh clashes had occurred intermittently. He suggested that we hold the meeting in our own residential area and agreed to give us formal permission.

We told the association people that we had no choice but to hold the meeting in the local park because that is what the police had advised. At this point, all hell broke loose. The leading Congress(I) men said that they would not allow the meeting to be held there because it would be a threat to the law and order situation in the area. We said that we would go ahead with our plans since we did not agree with their assessment. However, they continued playing on the fears of both Hindus and Sikhs so that utter confusion prevailed all around. People who were enthusiastic supporters of the meeting until the previous day were finding it difficult to express open support. Many told us that even though they were moral with us and felt that we were working for a good cause, they could not take an open stand on this issue, given the political atmosphere.

Just two days before the meeting, the Air India jumbo jet crash occurred. Even before the cause of the crash had been confirmed, the television and newspapers had screamed that it was the doing of Sikhs. In fact, even before the newspapers said it, the hearts of most Sikhs in Delhi and elsewhere were filled with fear that this crash might be used as another excuse to spark off violence against them.

This provided a further handle to the Congress (I) men. The pressure became so intense that we had to have an open confrontation with a leading Congress (I) man in the area and told him that we would go ahead with the meeting no matter how much he opposed it. At best, they could intimidate the mohalla people into not joining the meeting.

They then resorted to a stratagem that nearly paralysed us. They began to pressurise some of the leading Sikh families. We were confronted with a situation whereby Sikh men began to accuse us of jeopardising their safety. They pleaded with us to cancel the meeting. One elderly Sikh gentleman even said: “For you, it will all finish with this one meeting. If the meeting is successful you will get the credit for it. But if anything goes wrong, it is we who will pay the price for it. After al, we have to continue living in this mohalla. We cannot afford to alienate certain people. Can you save us if we get into trouble?”

We had to admit that we could not even save ourselves in case there was trouble, and yet we felt that such risks needed to be taken. Their fears were not really unfounded. Indiscriminate arrests of Sikhs were being reported both in Punjab and in Delhi. Special draconian laws were being used against the Sikhs. This had created a deep fear of coming out in the open. I had an uneasy feeling that given the prevailing atmosphere, many Sikhs would have liked to become totally invisible. The moral dilemma became nightmarish because there was no way of predicting the government’s behaviour.

We met the police commissioner again. He said the intelligence report indicated there was no fear of trouble. He promised to process our application at the earliest and gave us a go-ahead for the meeting to be held in Lajpat Nagar. By the evening of the 23rd June we managed to obtain his written permission, thinking that if we had that in hand, the opposition to the meeting would subside somewhat.

Power Games: However, it had the contrary effect. When the local Congressman learnt that we had approached the police commissioner directly, he seems to have become even more firm in his resolve to stop the meeting. He felt bruised by the fact that we had proceeded on our own when he had offered to mediate on our behalf with the local police station. In reality, the offer of mediation was only meant to make us grovel and depend on him while he got the power to pull the carpet out from under our feet. This became evident when he told us outright that he had already written a letter to the police and the municipal corporation on behalf of the residents’ association, saying this meeting should not be allowed because it could act as a threat to peace.

We appealed to the members of the association for their help and intervention. After several rounds of talk, some of them tried to convince the local Congressman that he should allow us to hold the meeting, especially since the local association had completely withdrawn by now. After many more hours of persuading and arguing, he agreed to accompany us and withdraw his letter of objection from the corporation office but he said the letter to the police would be left to their discretion, especially since we had the permission from the commissioner. The reason we got the permission from the top was probably that the Center was beginning to change its policy towards the Akali Dal and was in the process of clearing the way for a settlement and that we had invited no less a person than Sant Longowal; any adverse publicity might have proved an embarrassment to the government. It is quite likely that if the same meeting had been planned a couple of months earlier, we would not have gotten permission, no matter at whose door we had knocked. However, the Congress workers at the local level were not given a clear signal about the tentative change in policy. Hence their confusion. They could not oppose us outright but they dared not let it happen lest they get chided for losing control over their constituency.

Even with the police permission in hand, we were not at all sure we would actually be allowed to hold the meeting. This meant we could not publicise the meeting adequately. We were not particularly concerned whether a few dozen came for the meeting or a few thousand. For us, the meeting was not going to be a show of strength. But the Congress (I) man seemed to behave as if the holding of the meeting would bring down his prestige and be a challenge to his power. Hence no effort was spared to sabotage it.

It is significant that the local Congress (I) men are not among the richest or better off families of the mohalla. Most Sikh families are economically much better off than most Hindus in the neighbourhood. They have also been a traditional vote bank of the Congress (I). What then accounts for the power of these Congress (I) men who would otherwise be considered small fry?

Their link up with the local police and administration gives them clout quite out of proportion to their power. Most people would fear that they could easily be implicated in false cases by the police if they by chance happened to rub the Congress (I) men the wrong way. This was definitely our fear too. For Sikhs, this fear has acquired nightmarish dimensions. Any one of them could well be arrested under the antiterrorist act which allows them no redress even if they are innocent. Even their economic power cannot come to their rescue once the political and the state machinery is used against them.

| “By inviting a national figure from what men see as their political arena, we stepped into their domain and suddenly came to be treated the way a rival political formation would be treated” |

Though the Congressmen kept using phrases like “such and such is likely to happen”, the message that came across was “We have the power to make it happen.”

It is important to mention that at no point did any woman of the mohalla participate in the conflict or attempt to browbeat us. Some did express sympathy in private, at a personal level. It is noteworthy that what is called a residents’ association or community organisation almost invariably means “resident men’s organisation.” Our local residents’ association consists of “heads of households”, mostly older men, but younger men do come and sit in on meetings. Not once have we seen any woman, old or young, at a meeting or involved in decision making. In fact, women do not even get to vote in the election of office-bearers.

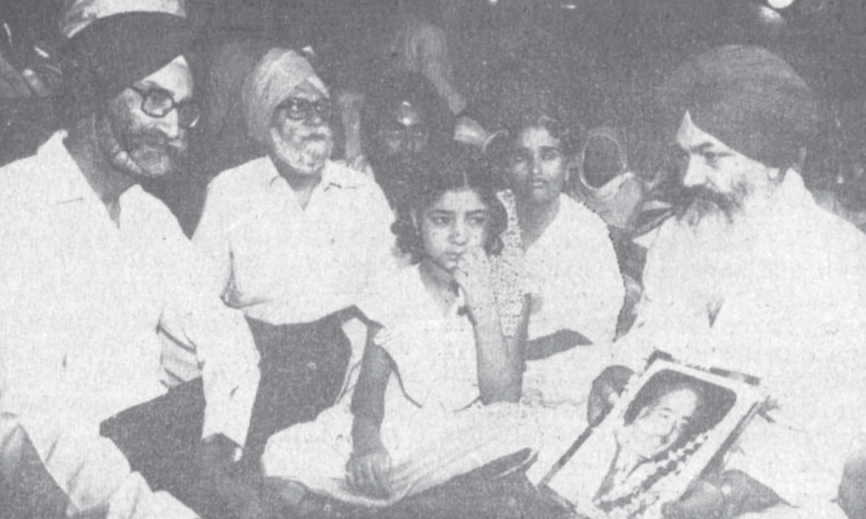

Sant Longowal with the picture of Shri Prabhu Dayal, his widow Atam Devi, and daughter Sant Longowal with the picture of Shri Prabhu Dayal, his widow Atam Devi, and daughter |

It is possible that had we held a women’s meeting and invited a woman uninvolved in electoral politics to honour Prabhu Dayal’s widow, the meeting would not have been as such a threat to the local powers that be. But by inviting Sant Longowal, a national figure in what men see as their “political” arena, we stepped into their domain and hence came to be suddenly treated in a way similar to the way a rival political formation would be treated. Even so, the fact that we were all women perhaps acted as some sort of protection. We were not perceived as a threat the way a group consisting primarily of men would have been perceived.

Outright Sabotage: Early on the morning of June 25, the day of the meeting, a woman from the mohalla came and informed us that all the three parks in our block were being flooded with water. We rushed down and found that the taps had been flowing full blast since the early hours of the morning. The taps could not be closed because they had been deliberately broken and parts were missing. Some parts of the park already had ankle-deep water and if the water kept gushing at the same speed, in a few hours we would have a virtual flood.

It took us an hour to locate the gardeners who would have some clue as to how to repair the taps. They were good enough to listen to our pleas and after about two hours of effort, managed to close the taps with wooden sticks and rags. In the meantime, the pressure to cancel the meeting kept mounting. The whole neighbourhood was charged with tension. Several Sikh men stayed away from work to be at home that day, fearing trouble in the area. Most people were unhappy at the way the meeting was being sabotaged but very few had the courage to challenge the saboteurs openly.

At about 10 a.m., the local tent dealer was to start making arrangements for erecting a stage, and fixing and setting up the microphones. Some of us were trying to drain out the water from the park. The tent dealer was discussing our requirements when he was called aside by some men. He was told in no uncertain terms that he would not be allowed to do his job. “What if your tent and mikes are destroyed?” he was asked. He got the message and disappeared from his shop for several hours.

By this time, it had become clear that going ahead with the meeting in the public space was full of risks. But we were not going to abandon it altogether. We had decided that if they did not allow us the use of public space, we would hold the meeting anyway, even as a small private meeting in our own house or office. We finally did decide to use our office terrace for the meeting. It had space for about 300 people if they squatted on the floor. Even this had its own risks. Some neighbours brought fearful rumours that the house might be damaged by miscreants.

The meeting was held as scheduled. In the few hours we had at our disposal, we hurriedly got some leaflets printed and distributed them in our neighbourhood. We arranged for microphones and lights to be fixed on the terrace so that those who could not be accommodated on the terrace could still listen, standing in the streets around the house.

Much before Sant Longowal arrived, hundreds of people had collected around the house. He was delayed by about two hours and yet people waited patiently for his arrival. Seeing those crowds, we were apprehensive that when he came, a stampede might ensue. When he arrived, for a few minutes the sudden rush of people wanting to get inside created a scene but there no slogan shouting or rowdy behaviour. The crowd behaved with remarkable dignity and restraint.

By the time Sant Longowal rose to speak, many more hundreds had assembled all around the house and in the park opposite. They cheered him and demanded that he make an appearance before them by coming close to the parapet. After that was done, they listened to him with rapt attention. There was about an equal number of Hindus and Sikhs. A good number of women and children were present in the crowd.

Can one then say that the fears were totally unfounded? In one sense, yes. In another sense, no. They were unfounded in so far as people are often forced to believe that riots happen only because of a conflict of interests between two groups. The experience of the last few decades had taught us that most riots do not happen that way. Most ordinary people prefer to live in peace rather than in constant fear of indiscriminate violence. Most riots are engineered by politicians for narrow political ends. So, the fear getting involved in any social or political activity which goes against the interest of powerful political parties or groups is a very legitimate fear.

Rural Party Hegemony: During the course of those five days, another important aspect of political organising was revealed. The Congress (I) workers did not seem to be opposed in principle to such a meeting. Their opposition was a symptom of a serious disease which has come to afflict our political culture at all levels.

Mrs. Gandhi was extremely wary of the emergence of any political power centres in the country other than those headed by the Congress Party. Leaders at the local level appear to harbour corresponding fears. They have all imbibed the postindependence Congress culture which teaches them to mistrust any political initiative that comes from any source other than the Congress.

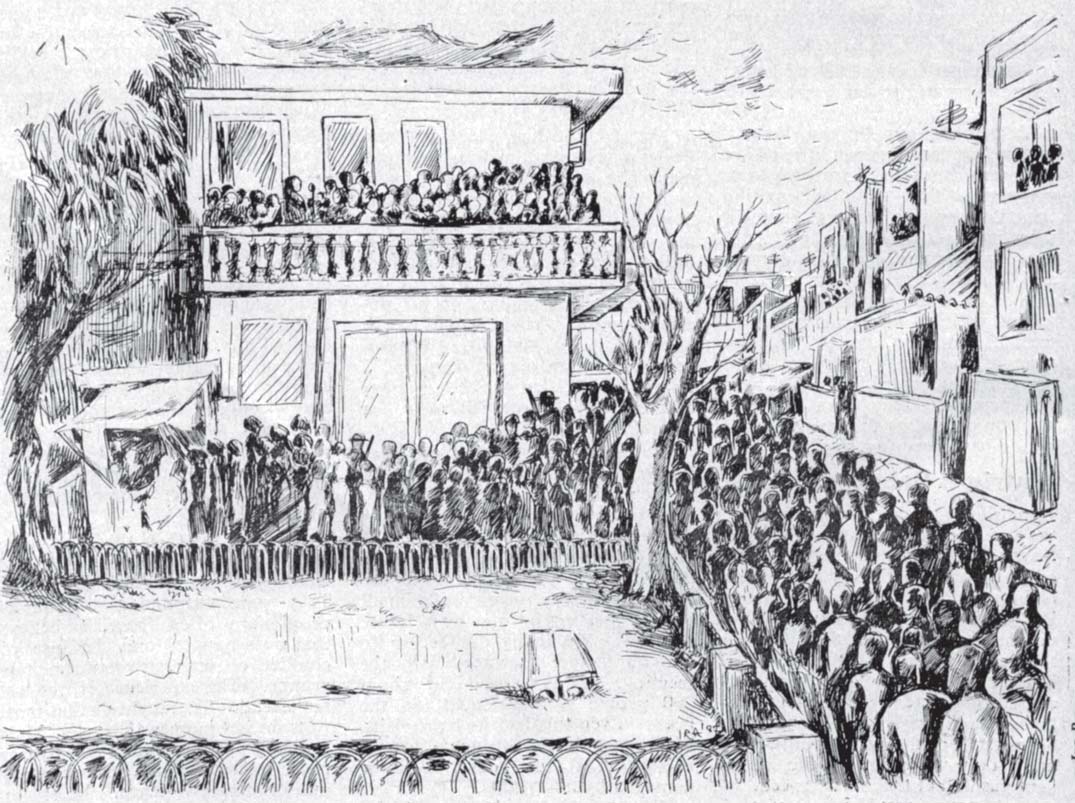

Making use of the public and private spaces- Making use of the public and private spaces-an artist’s view of the meeting from ground level |

Even at the height of the liberal Nehru era, the left front ministry in Kerala was toppled unscrupulously in order to ensure that the Congress maintained its hegemony both at the Centre and in the states. For the same reason Sheikh Abdullah, the popularly elected leader of Kashmir, was kept in jail for years to prevent the National Conference from holding power in Jammu & Kashmir. In the last decade, especially since the Emergency, the perpetual attempts to prevent regional parties from forming State governments have led to major and bloody conflicts. The toppling of the Left Front ministry in Bengal, the Telugu Desam in Andhra, the Farooq Abdullah government in Jammu & Kashmir and similar attempts in Karnataka and Tripura have had disastrous effects on the political life of India. The disease has not remained confined to the top. It is visible wherever Congress workers are to be found, from the mohalla and the village level to the urban corporation level to state legislatures and parliament. It is this mentality which triggered off such an intense conflict over our meeting even though there was a broad consensus in favour of it.

It seems that even more than the coming of Longowal, an opposition leader, to their mohalla, what perturbed the local Congress (I) men was that a major function of this sort should take place in their locality without their initiative or without someone having sought their patronage.

Would it have helped if we had first approached them and asked for their patronage? Unfortunately, the answer is “No.” Given the state of the inner functioning of the Congress party today, no local leaders, be they village level workers or chief ministers, dare take political initiatives without clearance from the top. The only thing they seem to have a free hand in is the ability to coerce the local government machinery into serving their narrowly focused personal ends so that they can easily become nerve centres of nepotism and corruption. Therefore, we would have needed clearance from the “high command” if we wanted the cooperation of local Congress (I) men. This would have come only if the party saw its own interests being furthered by our actions. Most leading political parties have learnt to survive by playing the game according to the rules laid down by the Congress (I).

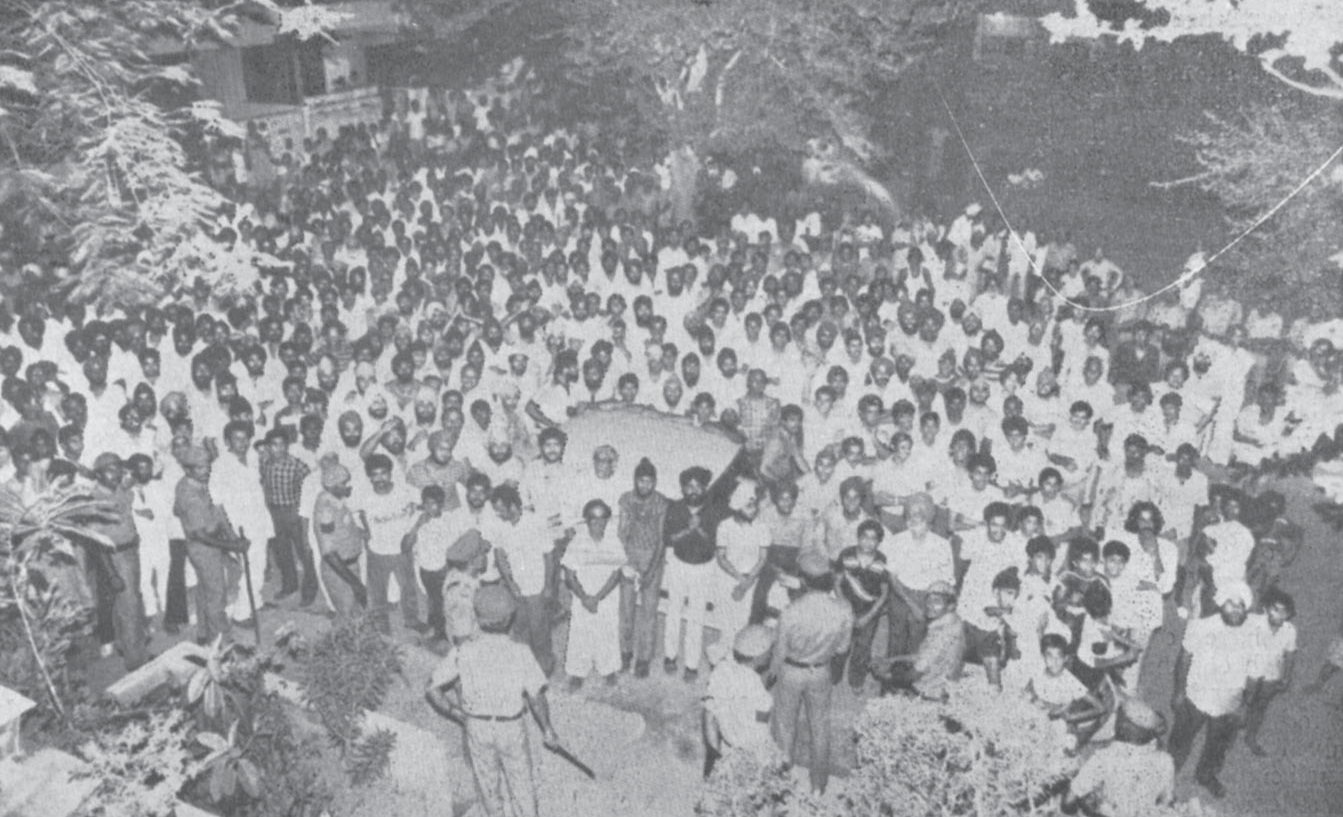

At the meeting At the meeting |

Independent Initiative Crushed: The whole affair would have become far more comprehensible to the local Congressmen had one of the opposition parties been behind this effort. In that case they might have felt less alarmed. Since we clearly had no such linkages and were functioning as a small independent group without any powerful patronage or connections, they seemed confused.

It added to their alarm that several local residents had spontaneously lent support to this meeting. This had to be nipped in the bud by creating enough hurdles so that very few people would dare act again on their own initiative. Over the last couple of decades, Congress (I) men at every level of the party hierarchy have been trained to treat public meetings as a show of strength against their rivals. The game of numbers has become very crucial to their politics. Since the opposition has tended to build its politics on the same lines, Congressmen are unable to conceive of any public meeting or rally organised without their approval, that can be intended as anything other than a strategy to upset their electoral base.

Control Through Corruption: Congress workers maintain control over their constituencies partly by fear and partly by acting as mediators between the people and the local level government machinery. If someone needs to make a complaint to the police about theft, it would help if they went through a Congress worker. The same mechanism is involved in getting a ration card made, or in getting permission to use public space for a marriage or religious function. All these events become occasions for demonstrating their power and patronage, which is ultimately mobilised for electoral purposes. It is on the basis of this vote gathering ability that a local Congress worker gets patronage from the higher-ups in the party. In return, he or she is allowed access to manipulating the governmental machinery for personal ends.

A view of part of the crowd on the street A view of part of the crowd on the street |

The ruling party has thus acquired a powerful vested interest in not letting the governmental machinery function smoothly and respond to people’s everyday needs as a routine matter. Everything requires the right “connections.” Ironically, the Congress (I) gives the name of social work to this organised racket of brokerage and corruption.

The inefficiency and corruption of the bureaucracy are, therefore, being constantly encouraged and nurtured by the political culture fostered by the Congress (I). It is no coincidence that Congress (I) today attracts antisocial elements hoodlums and crooks more than any other party. Even people who do not want favours from them fear their potential nuisance value and want to avoid any possible clash.

No matter what the complexion of the leadership at the top, the character of Congress (I) will remain virtually the same unless the party is willing to loosen its control over the local bureaucracy.

Culture of Cynicism: Even if a group of potentially independent people were to engage in such harmless activities as efforts to start youth clubs or neighbourhood sanitation drives, they would likewise be seen as a threat, and face similar if not identical hurdles. The local representative of the ruling party would either try to swallow them up or destroy them by putting so many hurdles in their way that they would lose heart. The opposition parties would perhaps be not very different except that since they are not in power nationally, their nuisance value is relatively limited.

This has far-reaching consequences. It creates a culture of total cynicism and demoralisation in ordinary people about the possibility of initiating any political or social activity on their own strength. Since a herculean effort is required to do the smallest of things, people have become weary of doing anything at all.

A feeling of helplessness has grown which partly gets reflected in the widespread belief that whatever action is possible has to be channelled through political parties. Therefore, people expect that only big political leaders can possibly solve any and all problems. If the existing ones fail, the tendency is to do nothing but hope and wait for “good” leaders to emerge. This mentality of paralytic dependence on the government and the ruling party gets manifested not only in situations of big political crises such as the one in Punjab but even in every day small things such as getting the sewers in the neighbourhood cleaned up.

If the municipal corporation does not do its job well, people can seldom think of any other initiative except petitioning and hoping that some good man at the top will listen to their faryard and act favourably. If he does not listen on his own, then people try and look for “connections” which can put pressure on him or else try and see if a bribe will work. Thus, the whole system of corruption and nepotism gets to thrive on the soil of people’s demoralisation and allows unrestrained power to those who control the machinery.

Sant Longowal garlanding Smt Atam Devi Sant Longowal garlanding Smt Atam Devi |

It has also fostered a cynical culture whereby anyone taking initiative in social or political matters is at once seen as someone who has a personal axe to grind. Since the Congress (I) men call themselves social workers, the work has become synonymous with hypocritical power-mongering so that no matter what action anyone tries to initiate, people at once begin to ask: “What will you get out of it?”

We have lost faith in initiating community action which is not for personal gain. Along with this has come a very rapid polarisation between different communities so that fewer and fewer people are allowed to act as bridges between different groups. I was really surprised that after the organising of this function, many old acquaintances began enquiring of me whether I come from a Sikh family since to them I seemed unduly involved in the cause of the Sikh community. What a masterly way of delegitimising concern for any human rights other than one’s own, and isolating whichever community is being victimised!

Things That May Help: The factor that helped us most in surviving the pressure and threats was that we did not get involved in the politics of numbers as a show of strength. We were clear: if not the big park, then we would use a small park – if not even that, we would hold it within our small house, while at the same time keeping it open to everyone. This ability to keep acting politically in the space where the public and the private world meet helped us to survive not only the pressures of the Congress (I) men but also the uncertainties created by the government machinery.

Linked to the game of numbers is the dependence on press publicity. Usually, press coverage is determined by the number of people attending an event. This tends to make political activists orient much of their activity towards somehow managing press coverage and using the amount of media attention they receive as the primary indicator of whether they achieved their political aims or not. We need to evolve other yardsticks besides that of press coverage for evaluating actions undertaken.

Even while we were compelled to hold the meeting in a private space, we kept the whole affair as public as possible. Even though the association finally withdrew, many of its members kept intervening on our behalf and advising us how to proceed. We did not enter into any private deals with the Congress (I) men. The fact that the conflict came to be enacted in full view of the public seems to have somewhat restrained the mischief-making power of those who were opposed to the meeting. We also made sure that we did not indulge in any counterthreat, no matter how angry we became. Thus, we were able to get the tacit support of a number of neighbours. This spontaneous support was worth more than all the official sanctions put together.

Even though there are enormous hurdles in the way of neighbourhood-based politics, we have to learn to avoid ghettoising ourselves in certain traditional locations which tend to confine political participation to a small number of people. In many ways, it is much easier to organise a national or a state-level conference than it is to initiate social and political work at the village or mohalla level. This is one reason why political activity in India tends to be very topheavy. There is an urgent need to concentrate our energies in bringing struggles for democratic rights closer to the everyday lives of people.

We have to work hard to change the very rules of the political game rather than get trapped by the rules laid down by the existing political structure. We have to find ways of ensuring that government machinery becomes more responsive to people’s rights. This requires building a system of checks and accountability that curtails the vast arbitrary power of the bureaucracy. Right now, government functionaries are accountable only to those at the top. They owe no accountability either to those who work below them or to the people whose lives they affect. We need to find ways in which the machinery is structurally altered so that it cannot act arbitrarily and has to be responsive to the wishes of the people instead of making them grovel for the most ordinary things, as it does now.

It is indeed important to get the bureaucracy out of the clutches of the ruling party politicians and see that they act according to rules and norms. But it is far more important to do away with the crippling restrictions and permissions required for doing almost anything. These thwart all spontaneous action and vibrant community life. To give one example, the right to hold meetings of a social or political kind should be an assumed right of every citizen. If those in power have reasons to stop it, then it is they who should have to explain through legal procedures the reasons for their action, rather than making the citizens explain their purposes, prove their bonafide and grovel before the bureaucracy.

Finally, women have not yet become a force to reckon with in community organising. The definition and the framework of politics, of change at any level, is not determined by women. When individual women here and there do enter the male-defined political domain, they do so either as unimportant adjuncts organising “women’s wings” which are directly or indirectly controlled by men or as individuals playing male-defined electoral and power games exactly as men do.

Only when women begin to organise in sufficiently large numbers, on their own terms, will we be able to conceive of and realistically discuss a truly “community based” organising, the character of which is bound to be different from that which goes by its name at present.