First published in Manushi Issue No. 80 (January – February 1994)

http://www.manushi-india.org/pdfs_issues/PDF%20files%2080/love_and_marriage.pdf

Feminists, socialists and other radicals often project the system of arranged marriages as one of the key factors leading to women’s oppression in India. This view derives from the West, which recognizes two supposedly polar opposite forms of marriage— “love marriage” versus arranged marriage. “Love marriages” are assumed to be superior because they are supposedly based on romance, understanding, and mutual love – they are said to facilitate compatibility. In “love marriages” the persons concerned are supposed to have married out of idealistic considerations while arranged marriages are assumed to be based on materialistic considerations, where parents and family dominate and deny individual choice to the young people. Consequently, the family arranged marriages are believed to be lacklustre and loveless. It is assumed that in arranged marriages compatibility rarely exists because the couple is denied the opportunity to discover areas of common interests and base their life together on mutual understanding. Moving away from family arranged marriages towards love marriages is seen as an essential step towards building a better life for women. To it, the social reformers add another favourite mantra—dowryless marriages as proof that money and status considerations play no role in determining the choice of one’s life partner. The two together—that is, a dowryless love marriage—is projected as the route to a happy married life.*

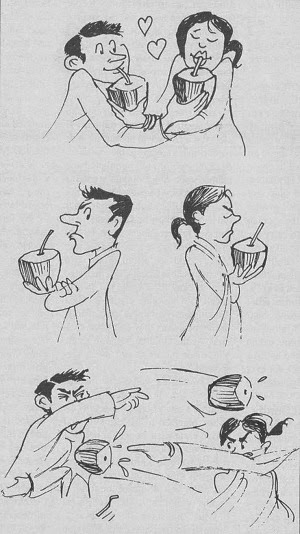

Does experience bear this out? From what I have seen of them, “love marriages” compel me to conclude that most of them are not based on love and often end up being as big a bore or fiasco as many arranged marriages. Among the numerous cases I know I have found that often there is nothing more than a fleeting sexual attraction which does not last beyond the honeymoon period. And then the marriage is as loveless or even worse than a bad arranged marriage. Nor have I found any evidence that material considerations do not play as important a role in people’s choice when they decide to “fall in love” with someone with a view to matrimony.

An American friend tells me his married aunt who was seeking a rich suitable husband spent many months going through women’s obituaries to identify widowers as potential husbands. Her modus operandi was simple: she would go through the daily newspaper and note down the funeral details of married women, then go to the funeral and try to make contact with the widower. If she found him attractive and rich, she pretended she was a friend of his dead wife. This is how she targeted eligible men in the hope that one of her encounters would lead to marriage. The social and economic status of the man would be carefully surveyed before he was put on her hit list. This may well appear as a rather farfetched example but falling in love with someone is often based on considerations not very different from those that decide marriages arranged by families.

The romance industry (films, novels) in the West tries to convince us that love is something that happens involuntarily – hence you “fall in” and “out of love.” But even their own romance churners keep women’s emotional aspirations neatly pigeonholed. The Mills and Boons Barbara Cartland heroines make sure the man they “fall in love” with is tall, dark, handsome, well educated and from a rich if not aristocratic family.

My colleague GiriDeshingkar tells me an amusing story of the time he worked as a pool typist in England. Like most Indian men, he never wore a wedding ring. Mistaking him as an eligible bachelor, his female colleagues showered him with attention and competed with each other in wooing him. However, as soon as they got to know through a chance remark that he was already married, they dropped him like a hot brick. No more teas and coffees and other gestures of attention. Suddenly he became invisible for them. They would not hesitate to discuss their boyfriends and love affairs in his presence. He found them absolutely cynical in their calculation of who they were going to select as a target for loving attention. The experience cured him of all naive notions about love and romance.

This does not surprise me because I have seen these calculations at work at close quarters. For instance, during my university days, I found most of my fellow Mirandians from an English speaking elite background determined to “fall in love” with a Stephanian and would not “stoop” to have a relationship with a man from Khalsa or Rao Tula Ram College, because those were considered low-status institutions, where people from ordinary middle-class backgrounds went to study. The additional qualification they looked for was that the man’s family own a house in one of South Delhi’s posh colonies. Thus men from colonies such as Jor Bagh, Golf Links or Sundar Nagar were much sought after. Likewise, sons of senior bureaucrats, ambassadors, and top industrialists could have the choicest pick among the beauties and cuties of Miranda House. But a man whose father was a small shopkeeper in Kamla Nagar or a clerk in a government office stood no chance, no matter how bright or decent he might be. I witnessed several instances of my fellow students ditching a man they had been having an affair with for years as soon as someone from a wealthier background appeared on the scene. Often they would not even bother to hide the crassness of their calculations; a friend conveniently “fell out of love” with her boyfriend who owned a motorbike in favour of someone who had a car to take her out on dates.

While many of my friends would have scoffed at the idea of their parents “arranging” for them to meet a man with a view to matrimony, they were only too eager to go to parties arranged by Stephanians so that they could pick girlfriends. In western campuses young people eagerly read notices of “Mixers” in order to find future mates:

Men do precisely what women do about “falling in love.” They take family status, who among her family are “green card” holders, and other such material considerations into account before they take the plunge.

While men and women may be somewhat more adventurous when choosing someone for a mere sexual affair, the same people tend to become far more “rational” in their calculations when “falling in love” is meant to be a prelude to marriage.

In the 1950s a study which is considered a classic on factors that determine love and marriage in America showed that it was easy to statistically predict the characteristics of the person a man or a woman is likely to fall in love with and marry. Three major factors that have a great influence on who a person falls in love with are proximity, opportunity, and similarity. Thus it is no coincidence that most whites marry whites and that rich people marry among themselves even in a “free” society like America where marriages are self contracted. Why then are we surprised if most Brahmins marry within the Brahmin fold or Jats and Mahars do likewise in the family contracted marriages?

Whatever the form of marriage, the motivations and calculations that go into it are fairly simple. The desire for regular sex, economic security, enhancement of one’s social status and the desire to have children all play a role in both kinds of marriages. Therefore, instead of describing them as “love” marriages, it is more appropriate to call them self arranged marriages. Love, in the sense of caring for another person, may even be altogether absent in these marriages. Therefore, I feel the term love marriage needs to be restricted to those marriages where people actually have a loving respect for each other and where there is continuing satisfaction in togetherness.

Self Arranged Marriages

Critics of the family arranged marriage system in India have rightly focused on how prospective brides are humiliated by being endlessly displayed for approval when marriages are being negotiated by families. The ritual of ladki dikhana, with the inevitable rejections women (now even men) often undergo before being selected, does indeed make the whole process extremely stressful.

However, women do not really escape the pressures of displaying and parading themselves in cultures where they are expected to have self-arranged marriages. Witness the amount of effort a young woman in western societies has to put in to look attractive enough to hook eligible young men. One gets the feeling they are on constant self-display as opposed to the periodic displays in family arranged marriages. Western women have to diet to stay trim since it is not fashionable nowadays to be fat, get artificial padding for their breasts (1.5 million American women are reported to have gone through silicon surgery to get their breasts reshaped or enlarged), try to get their complexion to glow, if not with real health, at least with a cosmetic blush. They must also learn how to be viewed as “attractive” and seductive to men, how to be a witty conversationalist as well as an ego booster — in short, to become the kind of appendage a man would feel proud to have around him. Needless to say, not all women manage to do all the above, though most drive themselves crazy trying. Western women have to compete hard with each other in order to hook a partner. And once having found him, they have to be alert to prevent other women from snatching him. So fierce is the pressure to keep off other grabbing females that in many cases if a woman is divorced or single she is unlikely to be invited over to a married friend’s house at a gathering of couples lest she try to grab someone else’s husband.

The humiliations western women have to go through, having first to grab a man, and then to devise strategies to keep other women off him, is in many ways much worse than what a woman in parent arranged marriages has to go through. She does not have to chase and hook men all by herself. Her father, her brother, her uncles and aunts and the entire kunba join together to hunt for a man. In that sense, the woman concerned does not have to carry the burden of finding a husband all alone. And given the relative stability of marriage among communities where families take a lot of interest in keeping the marriage going, a woman is not so paranoid about her husband abandoning her in favour of a more attractive woman. Consequently, Indian women are not as desperate as their western counterparts to look forever youthful, trim and sexually attractive marriage partners.

“Love” Marriage of Sunita

Let us take a few examples of “love marriage” without dowry and see if women fare much better in them.

When Sunita* was sixteen years old and still in school, she fell in love with Vinay who was then more than twice her age. She belonged to a well-off business family but was not well educated herself. Vinay lived in her neighbourhood and had by then had a number of affairs. When her affair was discovered by Sunita’s family, they were upset and tried to dissuade her from marrying Vinay because he was not particularly respected in the neighbourhood on account of his somewhat loose life. However, Sunita felt his “love” for her would change things and determined to marry him against her family’s wishes. Vinay’s family was not too happy with the alliance because they saw Sunita as irresponsible and silly and too young to handle a marriage with someone like Vinay.

However, the two insisted and much against parental opposition eloped with a view to pressuring their parents into agreeing to the marriage. Both the families felt humiliated and blamed each other. Sunita’s parents gave no dowry because they did not feel responsible for this marriage, nor did Vinay’s family make an issue of it. But they felt very angry when the two of them came to live with them because Vinay could not afford to set up a separate establishment. Their marriage seemed okay for a while but swiftly began to deteriorate due to Vinay’s drinking and compulsive womanizing. In the meantime, they had three children. As the children began to grow, Vinay became more and more irresponsible.

He would not even give her enough money for housekeeping, the children’s education and other needs. If she objected to his drinking and sexual escapades, he would beat her up. Soon thrashing her became a regular event. In the meantime, he got involved with a divorced woman and this affair began to take the form of regular cohabitation. The more Sunita objected, the more she got beaten. Since she had not been trained for a job nor was she well educated enough to pick up skills easily, she had to go back and seek financial help from her own father and brothers, in addition to the help she got from her mother-in-law, whose house provided Anita and her children home.

Thus, the very people Sunita had defied in marrying Vinay ended up providing her with the wherewithal for survival when her “love marriage” failed her. However, whatever little financial help came to Sunita from her natal family came more as a favour and as charity than as a right, even though she did not get her traditional due in the form of dowry. Her sisters, whose marriages were settled by their parents, all got handsome dowries and have fairly comfortable marriages, married as they are into wealthy families. Sunita’s husband was not as financially well off as her own father. Now she is the poorest of all her sisters and brothers and is virtually living on their charity as well as that of her in-laws.

By forsaking her dowry she has not gained anything—certainly not the right to a share in her father’s property. For years, the hostility of her father and brother to her self-arranged marriage prevented her from approaching them for help when her marriage began to crack up, because they would retaliate with: “It is your own doing. Why come and cry on our shoulder now?” Her sisters would get expensive gifts on festivals and other occasions, but not Sunita. What hurts Sunita most is that her sisters’ wedding anniversaries are celebrated with much fanfare. But the day of her wedding feels like a day of mourning. Neither of the two families want to remember that day for it brings back painful memories of humiliation and letdown.

Over the years, as her marriage deteriorated and she was on the verge of destitution, a small trickle of help began to flow towards her. Compare her situation with that of her two sisters. Had their husbands gone wrong, their parents along with other relatives could try and exercise a measure of influence on their husbands because of family bonds that come to be built in a family arranged marriage. Since Sunita’s father felt free to treat her self-chosen husband with contempt even when her marriage was fairly happy in the early years, the two families never built any bonds—nor can her parents claim any rights over him.

Falling Out of Love

Or take the case of Santavna. She was in her mid-twenties when she met Rajesh who was then a young university student struggling to make a living as an artist. Santavna was well placed in a private company. Though she came from a lower middle-class family and was not highly educated, by her hard work she got a good job and began to rise rapidly in her profession. She was and continues to be a good looking woman. Rajesh initiated a love affair with her, though he knew she was eight years older than him. In those days he was poor and struggling and she provided him financial as well as emotional and physical sustenance. However, his fortunes changed swiftly as he entered the world of journalism and made a successful career. With such rapid upward mobility, his social world also changed dramatically. He then began a series of extramarital affairs. In the early years, he was defensive about them and would keep protesting that his love was reserved exclusively for his wife. I was shown a number of letters of this type he wrote to his wife during the early years of surreptitious and guilt-ridden love affairs.

But as he became more and more successful, he had many more young and glamorous women available for affairs. Tension at home increased and led to crisis after crisis. Finally, he moved out of his house, abandoned his wife and two kids and began living separately, in all like a hood with another woman. Moving out was no big sacrifice because the organisation he worked for provided him the house. Soon after, he changed to a still better paying job and asked his previous employers to use whatever means they though, necessary to get his wife to vacate the house. She does own a flat in her own name, so she won’t be homeless. But being abandoned by her husband has left her emotionally shattered. Recently, he filed a case for divorce. Today her salary is much less than his. It is certainly not enough to enable her and her two children to maintain their previous standard of living. Rajesh has made no arrangements for child support so far. It is unlikely that the wife can get anything more than a pittance as a maintenance allowance for their children through the court.

The most distressing aspect of the breakdown of their “love” marriage is the vicious and nasty manner in which he goes around defaming his own wife. I heard both their versions. Both had a lot of charges against each other but comparing their accounts one got the distinct impression that his was exaggerated and in parts even untruthful. He knew he was behaving irresponsibly and had to justify it by painting her as a monster and a whore. Her being eight years older than him was repeatedly mentioned as though that fact alone justified his wanting to get rid of his wife. The same woman to whom he had written innumerable love letters, swearing lifelong loyalty and begging her to have patience with him, to never reject him even if he made lapses because he depended on her more than on anyone else, had now become so offensive that he refuses to even talk to her on the phone. His office staff have instructions that they are not to let her in if she ever comes to see him. Since this is a new job, he has been able to justify his weird behaviour by telling people in the office that she is a vicious monster who will beat him up if they let her in at all. Since this was a self-arranged marriage, the two families have little or no contact. Thus, there are no family members who can temporarily act as communication channels between the husband and wife and help them sort out this crisis.

Fear of “Love” Marriages

The westernised modernists insist that marriage ought to be a matter between two individuals, that interference by families makes it difficult for the couple to build a close understanding. Hence, they romanticize marriages carried out in defiance of families. Parental opposition is invariably seen as proof of their authoritarian conservatism. This is frequently the case. However, more often, it turns out that young people are making choices that are impetuous and based on no more than a flush of sexual passion, which does not carry a marriage very far.

The possibility of meeting with Sunita’s or Santavna’s fate is what keeps a lot of young women from wanting to have self-arranged marriages without the consent or participation of their parents. Almost all of my women students in the college I used to teach in told me that they would prefer family arranged marriages. They would say something like, “At our age, we can easily make a mistake of judgement. Men behave very differently when they are courting a woman and change in unexpected ways when they become husbands. In any case, we can get to know only the man by dating him. But when our parents arrange a marriage they look into the family background and culture as well. If they arrange the marriage they take some of the responsibility if things go wrong. But if we marry against their wishes, who will we turn to for support, in case the marriage does not work?”

For years I took such statements to be a sign of a woman’s low self-confidence and proof of mental slavery. It is only when dealing with cases of women undergoing marital maltreatment that I began to see that many of those who went in for self-arranged marriages did not necessarily fare better. Often they ended up worse off, especially those women who burnt all their bridges with their families during a love affair.

While the presence of a large number of family members rejoicing in the marriage can add to the couple’s joy and strengthen their bonds with each other, the lack of parental support and effective communication between the two families, leaving the couple to their own devices, can threaten the well-being of the marriage.

If a family arranged marriage threatens to fall apart, dozens of people will try to put in the effort to piece it together. However, in cultures where marriage is considered an individual affair its tensions and collapses are by and large left to the concerned couple to sort out all by themselves. That is perhaps an important reason why the rate of marriage breakdown is much higher in such cultures.

Most women in India feel far more vulnerable if they cannot count on their parents or brothers to come to their help at times of crisis. In almost all the cases of marital abuse that have come to Manushi in the last 15 years, women have come to seek help along with their brothers, sisters, aunts, uncles or a range of other relatives. The parental house is almost always the only shelter they can count on if thrown out of their husband’s home.

Not that adequate amounts of family support come to all those women who go in for family arranged marriages. Few parents are willing to take their daughters back if they want to leave abusive marriages. But most families do intervene and offer emotional and psychological support, and even some financial support, if the daughter is in trouble. This is an important factor which makes most Indian women desire active parental participation in their marriage.

While women are far more vulnerable if they lose the support of their parents, men too run considerable risks if their self contracted marriage estranges them from their own family. I give, as an example, one of the saddest cases I have witnessed closely. Ajay was a happily married, highly placed executive in a private firm and came from a very wealthy, propertied family. He started an affair with a woman colleague (let’s call her Kavita) who came from an ordinary lower-middle-class family. Kavita was already married to someone with whom she had first had a long affair. But since Ajay was “superior” in every material way, it did not take long for Kavita to fall out of love with her first husband.

When Ajay’s wife discovered the affair, she was so hurt that in a fit of anger she packed up her suitcases and left for her parental home with her daughter. Kavita immediately moved in with Ajay, thus foreclosing the possibility of a rapprochement between Ajay and his wife. Both of them filed for divorce from their respective spouses and had a week-long celebration projecting their union as a grand triumph of “liberated” love over traditional bonds.

Ajay’s parents were so angry at his irresponsible behaviour towards his first wife and child that they refused to make peace with his second wife who they saw as a scheming home wrecker who had married their son for his property rather than love. This sudden estrangement from all his family made him take to liquor. He became an addict. This affected his job and he began to slide downhill professionally. In the meantime, Kavita started her own garment export business with Ajay’s money and through his contacts, it began to flourish in no time. Consequently, she had no time for Ajay or even their child. Along with her success came a string of extramarital affairs.

As their career graphs moved in opposite directions, Ajay became more and more resentful of Kavita’s success and would often get violent when he found her with other men. The combination of too much drinking and constant fights at home made him emotionally unbalanced and he became mentally depressed. In revenge, he started having affairs with other women but that only made him more unstable. For a while, he found someone he grew very closely attached to but the woman left him saying she found it too painful to have an affair with a married man. Kavita refuses to divorce him till he transfers most of his property to her name. The two go around calling each other the filthiest of names, their marriage not only loveless but full of hatred for each other. Ajay now feels that his wife is only waiting for him to die so that she can take over his property. At this moment of grave crisis, he has neither the sympathy nor the support of his father (his mother is dead) or other family members because they never forgave him for his second marriage and think he deserves his fate. His isolation and failure in marriage have made him a total wreck.

Marital Compatibility

In the West, almost all marriages are self contracted. Yet, there is no dearth of marital violence and abuse in those marriages. In fact, many women in the West get beaten not just by husbands, but as often by their lovers or boyfriends. But the problem is not just due to a certain number of husbands turning abusive resulting in the breakdown of marriages. Equally often, marriages break down because of mutual incompatibility even when neither of the two spouses is guilty of abuse. Compatibility is a sort of miracle; it rarely happens spontaneously. More often, people have to work hard and patiently to understand each other’s requirements and try to meet at least to some extent each other’s highest priority mutual expectations.

Compatibility comes more easily if people respect each other’s family and cultural backgrounds and are both willing to participate in them as part of mutual give and take. Not too long ago a young woman came to seek my help in deciding about her marriage. She was very maladjusted with her parents and wanted to escape living with them. During her college days, she began an affair with someone from Orissa whereas her family came from U.P, She was confused about whether to marry him or not because while she thought she liked him, she did not like his family background. But she went ahead with the marriage anyway, thinking his family would be living in far away Orissa and would have no chance to encroach upon their married life. However, trouble started in the first month of their marriage. When his family came to Delhi to attend the wedding, they stayed with the couple for a few weeks. She could not tolerate the way they talked, the way they ate, nor anything else in the family culture. Soon she began to resent that her husband shared the culture of his family in many intimate things. She found his food habits offensive and his involvement with certain prayers and rituals unacceptable, among many other things. The more she tried to wean him away from them, the more his family traits began to assert themselves more vigorously. Within seven months, she was talking of divorce.

A woman runs the risk of marrying merely her own life if she makes a wrong choice of a husband. But if a man brings in a wife who does not get along with her marital family, he risks destroying the peace and well being of his entire natal family. The entry of a new daughter-in-law is like a blood transfusion. If the donor’s blood group does not match the recipient’s, the recipient could end up dead. The groom’s family often has to cope with enormous stress to make space for a new member whose loyalty cannot be counted upon and who could easily cause irreparable splits in her marital family.

Family Pressures

My impression is that it takes much more than two people to make a good marriage. Overbearing parents on either side can indeed make married life difficult for a young couple and often women have to put up with a great deal of maltreatment at the hands of their in-laws. But more solidly enduring and happy marriages are almost always those where the families on both sides genuinely join together to celebrate their coming together and invest a lot of effort and emotion in making the marriage work. Very few people have the emotional and other resources required to make a happy marriage all on their own. Two people locked up with each other in a nuclear family having to meet with varied expectations inevitably generate too much heat and soon tend to suffocate each other. The proximity of other family members takes a lot of the load off. They can act as glue, especially during times of crisis. In cultures where marriage is considered an internal affair of the couple with no responsibility taken by families on either side for the continuation and well being of the marriage, breakdown in marriages is more frequent.

There is also the negative side. In communities where families consider it their responsibility to prevent divorce as far as possible women do very often get to be victims of vicious pressures against breaking out of abusive marriages. Among several communities in India a divorced woman is viewed with contempt and parents often force their daughters to keep their marriages going no matter what the cost. Consequently, many end up committing suicide or getting murdered because they are unable to walk out of abusive marriages. Many more have to learn to live a life of humiliation and even suffer routine beatings and other forms of torture. However, in such cultures, divorced men get to be viewed with some suspicion and are somewhat stigmatised. (In the MARG-Eyewitness survey 88 per cent of the men and 86 per cent of the women said that they would stay together for the sake of children even if their marriage did not work).

In family arranged marriages, few parents are interested in marrying their young daughter to a divorced man, unless he is willing to marry a woman from a much poorer family (so that the family escapes having to pay a dowry) or marry a divorced woman or widow. In India, relatively few men resort to divorce even when they are unhappy in marriage. The stigma attached to divorce for men, if not as great as for women, is at least substantial enough to get them to try somewhat to control themselves. They know that they cannot get away with having a series of divorces, as they do in the West, and yet find a young, beautiful bride 30 years their junior. But this is only true for marriage within tight-knit communities where the two families have effective ways of checking on each other’s background. There is no dearth of instances nowadays in which parents fail to investigate the groom’s background and end up marrying their daughters to men who have beaten or even murdered the first wife. My impression is that this is happening more among groups who are marrying beyond their kinship groups through matrimonial advertisement or professional marriage brokers.

Inter-Community Marriages

Hollywood, Hollywood propaganda tells us that passionate romance is the foundation of a real marriage; according to these myth-makers marriage is and ought to be an affair between two individuals. Marriages between people who defy caste, class, community and other prevalent norms are seen as demonstrating thereby their true love for each other and are glorified. This is not only oversimplistic but highly erroneous.

Our crusades against social inequality and communal prejudices is one thing. The ingredients that make for a good marriage are quite another. A married couple is more likely to have a stable marriage if the spouses can take 90 per cent of things for granted and have to work at adjustment in no more than 10 percent of the areas of mutual living. The film Ek Duje keLiye type of situation is very likely to spell disaster in real life. The hero and the heroine come from very different regional and linguistic groups. They don’t even understand each other’s languages and communicate mostly through sign or body language – yet are shown as willing to die for each other. In real life this may make for a brief sexual affair, but not a good marriage. The latter depends more on how well people understand and appreciate each other’s language, culture, food habits, personal nuances and quirks, and get along and win respect from each other’s family. If the income gap is too large and the standards of living of the two families are dramatically different, the couple is likely to find it much harder to adjust to each other.

The willing participation of the groom’s family is very often crucial to the well being of marriage especially if the couple lives in a joint family with the groom’s parents. But even if the couple is to live in a nuclear family after marriage, the support of her in-laws will help a woman keep her husband disciplined and domesticated. Most of my friends who have happy and secure marriages get along with their in-laws so well that they are confident that if their husbands were to behave irresponsibly or start extramarital affairs, their in-laws would not only side with the daughter-in-law but go as far as to ask the son to quit the house.

Safety Measures for Women

I am not against self-arranged marriages but I feel they have a poor track despite pompous claims about their superiority. A self-arranged marriage cannot arrogate to itself the nomenclature of a love marriage unless it endures with love. My own experience of the world tells me that marriages in which the two people concerned genuinely love and respect each other, marriages which slowly grow in the direction of mutual understanding, are very rare even among groups and cultures who believe in the superiority of self-arranged marriages.

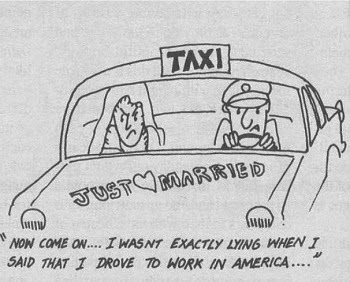

The outcome of marriage depends on how realistic the calculations have been. For instance, a family may arrange the marriage of their daughter with a man settled in the USA in the hope of providing better life opportunities to the daughter. But if they have not been responsible enough to inquire carefully into the family, personal and professional history of the man, they could end up seriously jeopardising their daughter’s well being. He may have boasted of being a computer scientist but could turn out to be a low paid cab driver or a guard in New York. He could well be living with or married to an American woman and take the Indian wife to be no more than a domestic servant or a camouflage to please his parents. He could in addition be a drunkard given to violent bouts of temper. His being so far away from India would isolate the young wife from all sources of support and thus make her far more vulnerable than if she were married in the same city as her parents.

Another case at the other end of the spectrum could end up just as disastrously if the woman concerned makes wrong calculations. Let’s say a young student in an American University decides to arrange her marriage with a fellow student setting out to be a doctor. Through the years that her husband is studying to become a doctor, she works hard at a low or moderately paying job to support the family. When he becomes a doctor she decides to leave her job and have a baby. In a few years, he becomes successful whereas she has become economically dependent on him. At this point, he finds a lot of young and attractive women willing to fall at his feet and he decides to “fall in love” with one of them, divorces his wife and remarries a much younger woman. The wife is left at a time when she needs a marriage partner most. All she can hope to do is to get some kind of a financial settlement after lengthy legal proceedings. But that is not a substitute for a secure family.

The factors that decide the fate of women in marriage are:

- Whether the woman has independent means of survival. If she is absolutely dependent on her husband’s goodwill for survival, she is more likely to have to lead a submissive life than if she is economically self-sufficient.

- Whether or not her husband is willing and equipped to take on the responsibility that goes with having a family.

- Whether or not a woman’s in-laws welcome her coming into the family and how eager they are to make it work.

- How well the two families get along with and respect each other.

- Whether or not there are social restraints through family and community control on men’s behaviour. In societies where men can get away with beating wives or abandoning them in favour of younger women, women tend to live in insecurity. However, in communities where a man who treats his wife badly is looked down upon and finds it harder to find another wife because of social stigma, men are more likely to behave with a measure of responsibility.

- The ready availability of other women even after a man is known to have maltreated his wife tilts the balance against women. If men can easily find younger women as they grow older while women cannot as readily find marriage partners when they are older or divorced, the balance will inevitably tilt in favour of men irrespective of whether marriages in that culture are self arranged or parent arranged.

- Whether or not her parents are willing to support her emotionally and financially if she is facing an abusive marriage. Most important of all is whether her parents are willing to give her the share due to her in their property and in the parental home. In communities where parents’ expectation concerning a daughter is that only her arthi (funeral pyre) should come out of her husband’s house, family pressure can prove really disastrous.

Undoubtedly, there are numerous situations whereby family elders do take an altogether unreasonable position; defiance of their tyranny then becomes inevitable, even desirable. Parents can often go wrong in their judgements. Parents must take into account their children’s best interests and preferences if they are to play a positive role.

We have to devise ways to tilt family support more in favour of women rather than seeking “freedom” by alienating oneself from this crucial source of support over romanticising self-arranged marriages and insisting on individual choice in marriage as an end in itself rather than as one means to more stable, dignified and egalitarian marriages.