As a follow up to my 1996-97 vintage documentary film “Mera Bharat Pareshan” that narrates the woes of farmers as a result of draconian laws and policies implemented by the Nehruvian Congress as part of its farcical socialist agenda, I am now sharing an article I wrote on the same theme in 1992.

This article was first published in Issue No. 73 of Manushi journal under the title, Cutting Our Own Lifeline: A Review of our Farm Policy. But it has becomes all the more relevant in the context of politically motivated protests against farm policy reforms recently introduced by Modi government.

The three landmark laws recently enacted by Modi government that have freed the farm sector from needless and harmful sarkari controls are:

- The Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, 2020. This allows the farmers to sell their produce to whoever they please anywhere in India in addition to the option of selling through APMC mandis at Minimum Support Price (MSP); For decades farmers battled to free themselves of corruption ridden and extortionist APMC where heavy tax burden is imposed on farmers plus they have had to pay big commissions to wholesalers plus bribes to APMC officials;

- The Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement of Price Assurance and Farm Services Act, 2020. Thanks to this new law, farmers can enter into contract for selling their produce to corporate buyers like Big Basket or even large cooperative sector buyers like SAFAL. This will enable them to get advance payment and assured price for their produce. As of now most farmers have to go for distress sales after harvest when prices are down;

- Essential Commodities (Amendment) Act, 2020. This amndment scrapped the British vintage Act which punished farmers for stocking any farm produce that government declared as “essential” or selling it outside government approved mandis at government approved rates. Countless farmers have been jailed for defying this colonial minded law.

Since I am not from a farm family, most of what I learnt about the plight of our farmers is on account of my 20-year long association with farmers’organizations, especially the Shetkari Sangathana of Maharashtra led by Late Sharad Joshi. If Joshi had been alive and active today, he would have been far more effective than Modi government has been in countering the misleading propaganda and agitation against these laws.

This article explains all that was weighing the farmers down and some of the steps needed to set things right. Those not familiar with the kind of draconian restrictions farmers suffered under Nehruvian socialism, are likely to find the following account useful in assessing the worth of newly enacted laws.

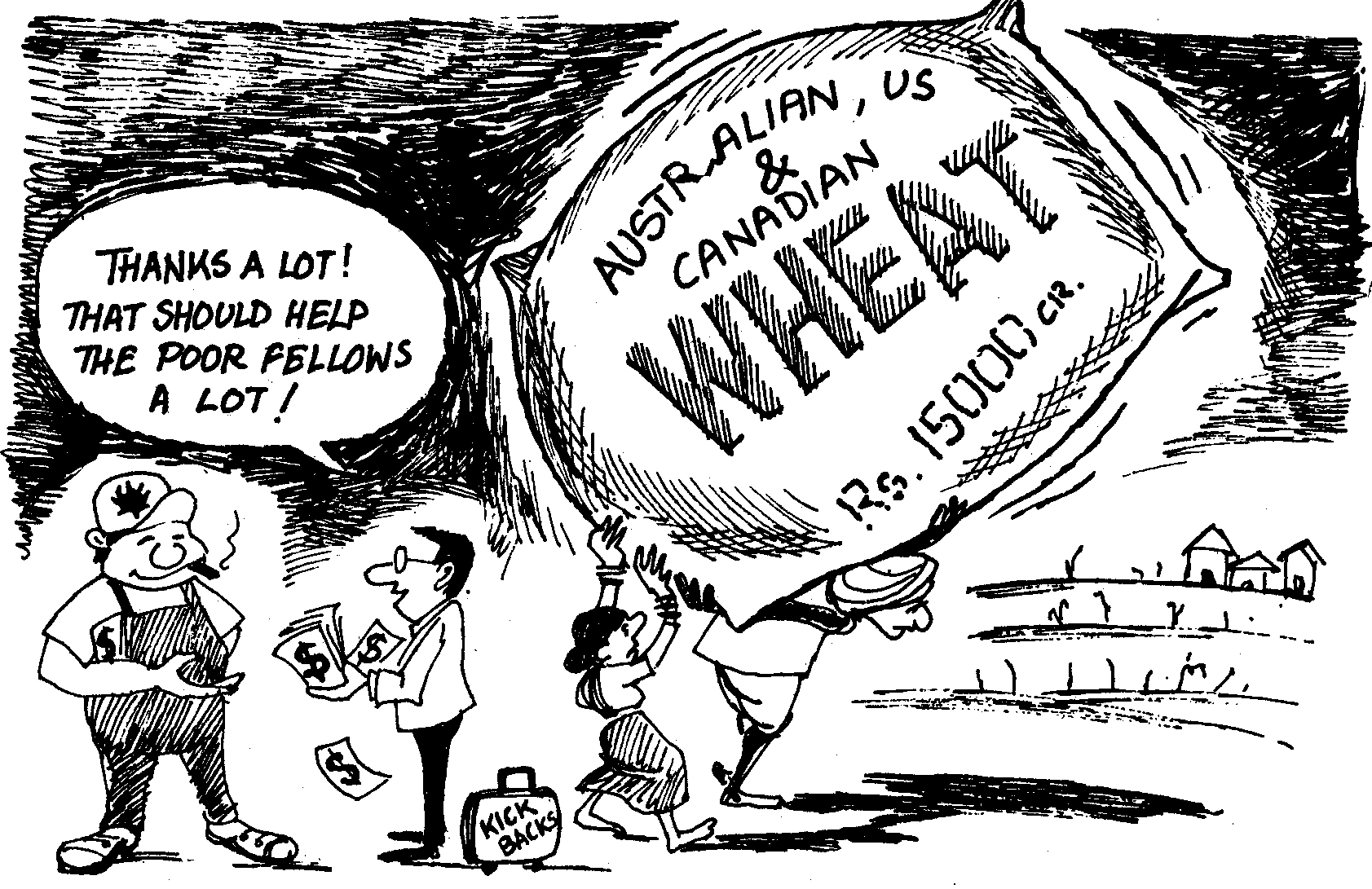

The decision of the Government of India to import nearly 3 million tonnes of wheat from Canada, US and Australia at the cost of Rs 1,500 crores to be paid in foreign exchange, has reopened the debate on the agrarian question. Import of foodgrains on this scale after years of boasting about self-sufficiency in food, calls for attention in itself. Those who oppose this decision are particularly incensed by the fact that this wheat was purchased in the international market at a price higher than the domestic procurement price of Rs 280 per quintal fixed by the government for domestic wheat producers. The landing price of this wheat, which includes a freight charge of about $30 per tonne, is about Rs 530 per quintal, almost twice as much as the domestic procurement price.

According to the prime minister’s own admission, this is not a crisis year for Indian agriculture. There has been no major drought or crop failure. How then do our policymakers rationalise import of wheat amounting to half of this year’s wheat procurement? The food secretary, Tejinder Khanna, justified this decision saying: “If the same quantity was purchased from the domestic market, the prices would have shot up.”(Times of India, November 14, 1992). This is a clear admission that this import is part of a strategy of price warfare against the peasantry, an attempt to browbeat the Indian farmers into selling their produce at artificially depressed prices.

The UnitedNations Food and Ag-ricultural Organisations (FAO) expects India to import an additional 500,000 tonnes of wheat, in addition to three million tonnes already purchased by it from the United States, Canada and Australia. In its latest “Food Outlook” report, FAO says the rise in Indian imports— is mainly because of below target procurement and government’s policy to rebuild stocks. (Times of India, December 26, 1992)

This import is clearly a measure of retaliation against the reluctance of the wheat-producing peasantry of North India, especially Punjab, to sell their produce at the government-fixed below-market price of Rs 280 per quintal. This year the Punjab government had forbidden the artias (private grain traders) from operating in the mandis of Punjab while the government was carrying out its procurement operations, in the expectation that the farmers would be compelled to sell more of their stocks to the government The district administrators were asked by the Chief Minister of Punjab to let the grain dealers know that no trucks carrying grain would be allowed to move out of the state and if they flouted this “order” their licences would be impounded. The farmers of Punjab tried resisting this illegal coercion to some extent. Many held back their stocks until such point as they could sell in the open market. As a result, this year’s grain procurement, which has been declining in the last few years, touched a record low. Two years ago it was 10 million tonnes. Last year it came down to 7.7 million tonnes. This year the government could procure no more than 6.35 million tonnes. Government stocks had indeed touched the very bottom with less than 2 million tonnes of wheat left in state godowns. Yet, it is noteworthy that the open market price went no higher than Rs 330 per quintal — substantially lower than what the imported wheat has cost us. Subsequent to the arrival of imported wheat, the prices have fallen further even in the open market.

Still More Grain Imports Expected: The UnitedNations Food and Agricultural Organisations (FAO) expects India to import an additional 500,000 tonnes of wheat, in addition to three million tonnes already purchased by it from the United States, Canada and Australia.

In its latest “Food Outlook” report, FAO says the rise in Indian imports— is mainly because of below target procurement and government’s policy to rebuild stocks. Times of India, December 26, 1992.

Tejinder Khanna, the food secretary, recently made the surprising announcement that the government is considering the import of jowar from the US, which grows coarse grains as cattle feed. He said this year’s crop of coarse grain in the US had been contaminated by certain harmful weeds and, therefore, found unfit even for American animals. This is the stock our food secretary intends to buy for consumption by the Indian people and to depress the prices of Indian jowar. He assures us that “to test its acceptability, US is willing to send a gift consignment of 100 to 200 tonnes.” (Economic Times, November 13, 1992).

Poorly Thought Out Bluff: It is being argued that this was the best option for meeting the requirement of the public distribution system. The Prime Minister defended the decision to import wheat as one based on “timely anticipation.” (Times of India, November 14, 1992). He said the government was advised to import wheat in July-August last year when a shortage of rainfall created fears about the likelihood of drought. But then he admits that the conditions changed dramatically in September. That this is a poorly thought out bluff becomes obvious when one considers the following :

- The contract for the wheat import was finalised in October—that is, after the predictions about a likely drought were proven wrong with a good rainfall in August-September.

- The Kharif rains of July-August have little to do with the rabi crop of wheat. In fact, late Kharif rains in August-September brighten the prospects of a good rabi crop. Therefore, the decision to import in October seems absurd. Our policymakers are probably not aware of the nuances of the agricultural calendar.

- The delivery for the American wheat is scheduled for March-April 1993, which is the harvest time of the Kharif wheat crop in Punjab. Thus, it seems that the decision to import was not really linked to an anticipated shortage in domestic production.

Rustam Vania Rustam Vania |

Is it likely that it was motivated by factors similar to the ones that prevailed in the Bofors deal?

Tejinder Khanna, when specifically put this question gave a reply that should win him an award in naivete. “The wheat has been bought directly … through the government agencies and there is no question of involvement of any middlemen or agents at any stage.” (Indian Express, November 9, 1992). Does that mean the commissions are coming directly to those in the government who make these deals?

In fact, now it is being admitted that due to a good monsoon, the country is set for a record production of more than 176 million tonnes of foodgrains in 1992-1993, though still below the official target of 183 million tonnes. But our policymakers insist that the country might still have to import more wheat because farmers may be reluctant to sell their produce at the government fixed price. (Economic Times, December 16, 1992).

Even for government spokesmen it would be difficult to pretend that the import of wheat is in tune with their much-flaunted liberalisation policy since our government is using (he might of the state to subdue our farmers through unfair competition. Nor does the government decision seem rational if it still wanted to attain the objective of achieving self-sufficiency in food grains.

It is strange that despite having become enthusiastic new converts to the internationally fashionable mantra of free trade as a key to economic prosperity, our policymakers are not embarrassed to resort to such harsh interventionist measures against farmers. The import of foreign wheat might have been justified had it cost less than the domestic wheat. This decision to import seems particularly inexplicable when one considers that it is being paid for in foreign currency. To fritter away our borrowed foreign exchange in a dumping operation of wheat, .of all things, cannot be considered proof of good economic sense.

R.K. Laxman, Times of India R.K. Laxman, Times of India |

Better Alternatives to Imports of Foodgrains: The situation created by inadequate procurement response could have been met more effectively and with far more grace by any one of the following three measures, or a combination thereof :

- Pruning the list of the beneficiaries of the Public Distribution System (PDS) to exclude the well-to-do. For example, by linking it to Food for Work programmes we can ensure that it reaches the poor, especially in villages.

- Quiet purchases of wheat in the open market.

- Procurement and issue of coarse grains like bajra and jowar to make up for the deficit in wheat procurement wherever possible.

No doubt grain prices would have risen had the government agreed to purchase at the open market price, but that would have had some good consequences as well. Higher prices would have given a boost in the coming years to wheat production, which has stagnated at 54 to 55 million tonnes, even while the demand is continuously going up. For the last three years, foodgrain production, in general, has been stagnating in our country. This is the fourth year when it is hovering between 170 to 174 million tonnes. Unremunerative price of foodgrains is one of the major reasons for this stagnation.

Disincentives to Farmers: Our past experience has shown that imports unless they bring in new technology, have invariably discouraged production, as for instance happened with PL 480 food imports from the US. Only when we cut down on food imports did we get going with our green revolution in the late ’60s.

In his recent address to the first Agricultural Science Congress organised by the Indian Agricultural Research Institute, the Prime Minister cautioned the nation about the fall in foodgrain production due to diversion of land to relatively more lucrative crops. He said the country needed to double or even triple its food output in the next five to 10 years, given the rate of population growth and called upon agricultural scientists to find ways and means of performing this task.

Scientists don’t produce grain. Farmers do. No matter how good the scientific input in devising high yield variety seeds and how successful their lab experiments, if farmers are not enthusiastic about growing foodgrain and are shifting to relatively more lucrative crops, foodgrain production cannot go up. In the short run, the government may squeeze the farmers into selling at below-market prices; ultimately it cannot force them to produce crops they consider uneconomic.

It is a myth created by the urban elite that only rich farmers grow cash crops, whereas the poor grow only foodgrains for their own subsistence. That amounts to considering the poor too foolish to know their own self-interest. They would be even poorer if they stuck to this schema. It is common for poor farmers, even in dryland agriculture, to grow whatever cash crops they can manage—potatoes, peanuts, bananas, tobacco. Thus, it is not just the much-abused rich farmers who will shift away from foodgrains if they don’t get adequate returns, even the poor farmers will do so.

These days our policymakers are never tired of saying we need to bring about economic efficiency and close down loss-making industrial units. Why then are farmers expected to stick to those crops which they find unprofitable? Our policymakers ought to remember that they do not possess the kind of instruments that Stalin wielded to make the peasantry accept state diktats. It was only by exterminating large sections of the peasantry that even Stalin could force his will on the peasantry. In the process, he destroyed the economic viability of the Soviet Union.

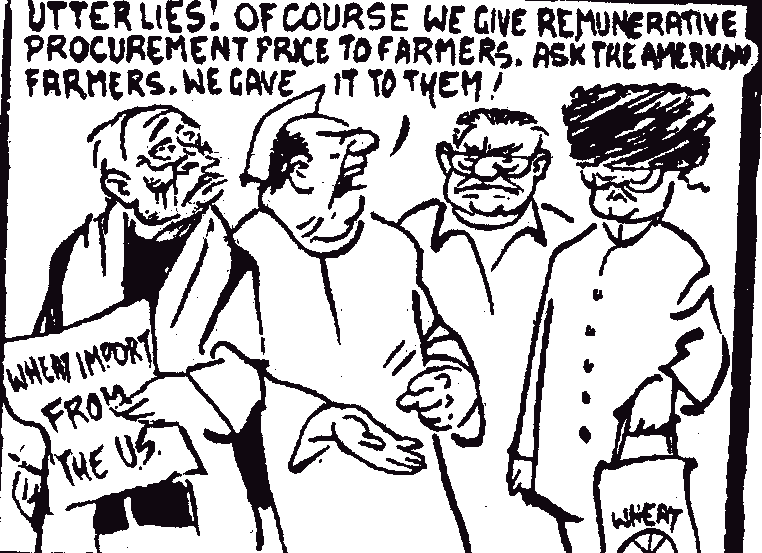

Rustam Vania Rustam Vania |

Effects of Good and Bad Prices: Prices play a crucial role in the production decisions of farm families. Even at the national level, we have had clear proof of this, during the ’50s when India was heavily dependent on food imports, agricultural prices stayed depressed and the production stagnated or declined. The Indian government abandoned its policy of food dependency only when India experienced arm twisting tactics by the US during the Indo-Pak war. In the spring of 1966, the government imported from Mexico 18,000 tonnes of a high yielding variety of wheat, to be used as seed. The international market price of wheat at the time was Rs 54. The Indian government announced a procurement price of Rs 76, thus giving the farmers of Punjab the required incentive to bring about a revolution in grain production. After six years, however, the price incentive was withdrawn on the plea that the farmers should now share the gains of the green revolution with the consumer. The result of protecting the interest of the urban consumer at the cost of the peasantry is that over the years foodgrain production has begun to stagnate.

The experience of milk production is equally telling. During the period 1971 to 1985, Gujarat, which was the hub of Operation Flood and the biggest beneficiary of the huge quantities of milk and butter-oil imported from the European Community (EC) countries, lagged far behind in milk production with a mere 4 per cent rate of increase as against an average of 6.5 per cent for the rest of the country. This despite the much-touted achievements of the government-sponsored cooperatives of milk producers in Gujarat. It was the dry and arid Maharashtra which produced the best results in milk production with a 10 per cent increase during the same period. This was because Maharashtra’s milk producers had obtained better prices, particularly for cow milk. The academic debate on Operation Flood in India has avoided answering this question. Why is it that the European Economic Community EEC continues to offer milk producers attractive prices rather than slash milk prices, even if it means dumping the surplus ‘mountains of butter’ and ‘lakes of milk’ as gifts to takers like India? As a direct contrast to the EEC, India’s response is to gratefully accept these gifts to bring down milk prices even at the cost of discouraging domestic production.

Rich Countries Heavily Subsidise Agriculture: The policies followed in the developed countries present a stark contrast to those followed in India. In an excellent and well-documented article reviewing world agriculture (Economic and Political Weekly, September 26, 1992), Ashok Gulati and A.N. Sharma establish a longstanding contention of the farmers’ movement, that many of those countries which are supposed to have performed economic miracles, have one thing in common. They all heavily subsidise their agriculture. In marked contrast to the policies in economically advanced countries, government policies of poor countries such as India, Bangladesh and Pakistan result in negative subsidies, that is the peasantry is actually being economically drained off through price controls, rather than subsidised. This is a major reason for the continuing rural poverty in South Asia. Most professional economists have hitherto denied or ridiculed this basic fact that Indian farmers are getting an unfavourable deal through government interventions in agricultural prices.

Among the advanced countries, Japan tops the list in extending farm subsidies, amounting to 72.5 per cent of its agricultural produce. The comparable figures for some of the leading exporters of agricultural produce are :

| USA | Canada | EEC |

| 26.17% | 33.50% | 37.00% |

Even the newly emerging industrial powers of Asia give huge subsidies to their agriculture. The figures for the two leading giants are :

| Korea | Taiwan |

| 60.67% | 22.33% |

However, India’s peasantry bears a negative subsidy of minus 2.33 per cent. The negative subsidy is calculated on the difference between the price at which the farmer has to sell the produce within the country and the price he would have got, if there was free international trade. Pakistan does even worse than India and taxes its farm sector to the tune of minus 21.80 percent.

The crop specific figures are no less revealing. The United States, Canada and the EC 10 countries are among the largest exporters of wheat primarily due to protection. Their subsidy figures are :

| USA | Canada | EEC |

| 40.67% | 36.17% | 32.27% |

Once again, the poorer economies are the ones to impose high taxation or negative subsidy on its wheat producers.The figures based on the average of 1982-1987 prices are :

| Pakistan | Bangladesh | USSR | CHina | India |

| 32.20% | 28.30% | 30.00% | 05.50% | 03.83% |

Since 1987, the tax or negative subsidy for the wheat growers of India has gone up due to the devaluation of the rupee. It is the same story for rice, cotton and other crops. It is noteworthy that those governments which impose negative subsidies through price controls are mostly the ones which have to import food.

The main instruments of the US government have been direct payments to farmers, market price support programmes, and input subsidies. The European Community intervenes mainly through its Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and uses border measures, market support prices and export subsidy mechanism for helping farmers. The price support element of the CAP now accounts for about two-thirds of the entire EC budget. Japan’s agricultural policy concentrates on food security, narrowing the gap between farm and non-farm incomes and on improving productivity. It uses price support programmes and restrictions on imports for carrying out these policies. As the leading industrial power it would be far cheaper if Japan were to import food. Yet, the Japanese emphasise the social and political role of agriculture rather than its strictly economic role and treat rice almost as a “defence item”. There is a total ban on rice imports in Japan despite the fact that its price is five to six times that of the international market.

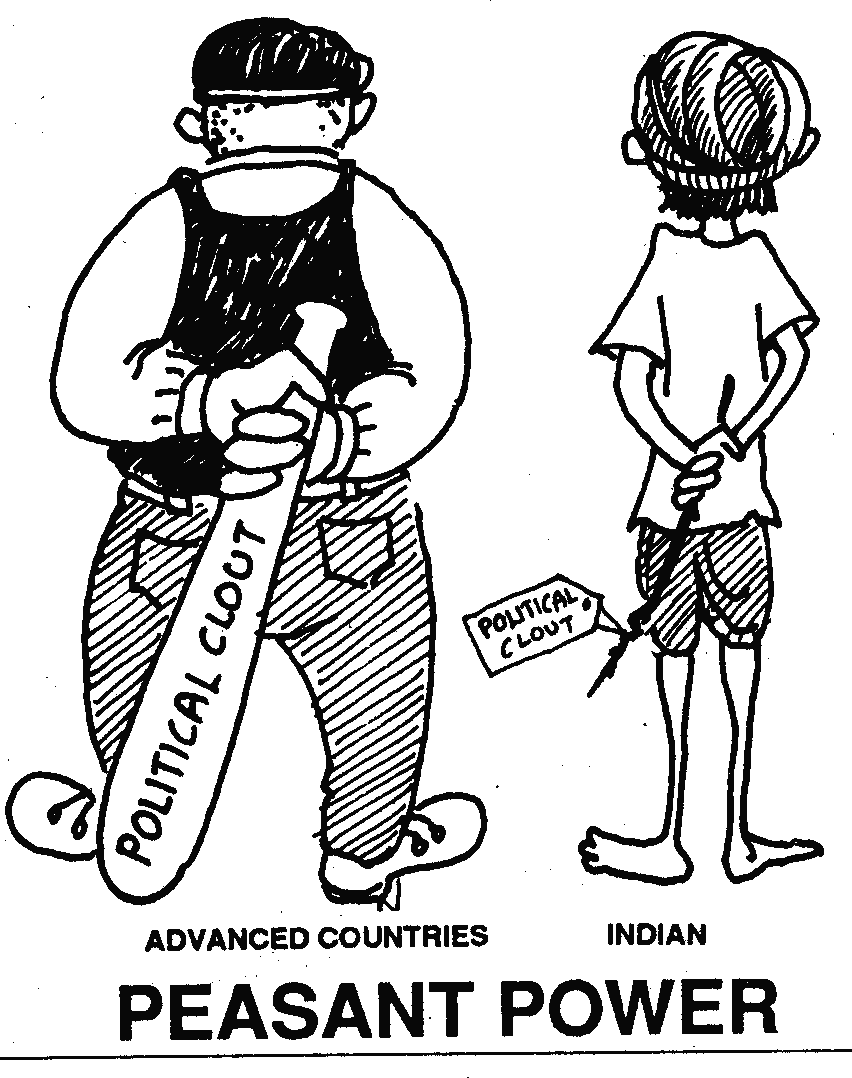

Thus, in most developed countries, the governments give all manners of economic incentives to farmers to help them in finding foreign markets, at the same time protecting them from agricultural products from other countries. In almost all the developed countries, the farmers have enough clout to be able to resist imports, including those of cheaper and better quality commodities. For example, this summer the French farmers blocked highways to protest against the import of beef from England at rates cheaper than prevalent in France and were successful in stopping those imports. Currently the French government is locked in a major battle with the US government because of its refusal to cut down on oil subsidies to French farmers, thus making it difficult for American soyabean growers to sell their product at competitive prices. The American government’s threat to impose a 100 per cent import duty on French wine entering the US has triggered off a massive protest by the French peasants. Whatever the outcome of this battle, some things are certain.

- Despite the peasantry being a small proportion of the overall population in developed countries (in the US it is no more than 2 percent of the total population), it exercises tremendous clout with the government of its own country.

- No developed country subjects its own peasantry to unfair competition. Mostly, they are not even expected to prove their worth in the international market, but rather given enormous subsidies for their protection.

- Agricultural development is very central to the thinking of economic planners in advanced countries, rather than regarded an unfortunate nuisance as in India.

A recent issue of Research Observer, the half yearly publication of the World Bank, documents how advanced countries are increasingly invoking anti-dumping laws to restrict exports from developing countries. It speaks volumes for the sorry plight of the Indian peasantry that despite constituting 70 percent of our population, it lacks the clout to successfully prevent our government from dumping foreign food products in India—after purchasing at higher than domestic prices.

Rustam Vania Rustam Vania |

Price Control through Crippling Restrictions: In India, by contrast to Japan and other developed countries, crushing state interventions impose a variety of restrictions on the peasantry in order to prevent them from selling their goods at market prices, both within the country and outside of it. This method has become the key instrument of taxing the peasantry, leading to a situation of negative subsidy. For instance, in the case of wheat, government retains the right of preemption in states like Punjab and Haryana, and informally even bars private traders from buying. There have been phases when severe zonal restrictions were imposed, that is, interstate movement of wheat within the country was forbidden. Even now, as happened this year, informal controls were imposed on the movement of grain out of the states of Punjab and Haryana.

Rice is procured through a levy on traders and millers at a price fixed by the government. While there are no restrictions on the movement of non-levy rice, some states impose informal restrictions on the inter-state movement of paddy/rice to facilitate procurement in the state. For example in Thanjavur district in Tamil Nadu, the government has monopoly over procurement and paddy is not allowed to move out of the district.

Thus, for the farmers, India is not a unified single territory. Economic borders are created for them arbitrarily. In Maharashtra, cotton is procured under the monopoly procurement scheme and farmers are forbidden from selling in other states and have to pay hefty bribes to the police if they want to “smuggle” their produce to neighboring states when prices are higher there. The same is true for farmers from Andhra Pradesh or Madhya Pradesh wanting to sell their produce in Maharashtra.

No less crippling are the restrictions on processing of farm produce. Rice growers are forbidden from husking their own paddy without getting a licence from the government. Ginning of cotton is a simple process and was traditionally done at the village level. But today only licensed gin mills are allowed to gin cotton. Cotton growers can not gin the cotton they produce even though this simple activity would enhance their profit margins considerably as well as give them useful by products. Likewise, if the apple producers in Himachal Pradesh were allowed to make cider and milk producers of a milk surplus state like Maharashtra were permitted to process the milk, they would not face the seasonal marketing crisis as they do now. The list of restrictions on the agriculture sector are endless.

Hijacking of Support Prices: The Agricultural Prices Commission (APC), appointed by Lal Bahadur Shastri in 1965 with the view to providing the requisite price incentives to farmers, functioned according to Shastri’s vision only in the first few initial years. With the end of the political and economic crisis after of the Indo-Pak war, the usual bureaucratic inefficiency, complacency and anti-farmer bias crept in the functioning of the APC. Defective and inadequate collection of data, erroneous methodology and deliberate undercalculations in the prices of agricultural inputs became the hallmarks of its price fixation policy. The cost data of APC contains such absurdities as the following: In 1977, the cost of spraying insecticide was put at one paise per one hectare of wheat while determining that year’s support price for wheat!

Its estimates of irrigation costs to farmers have often been so low that they would not even cover the cost of electricity charges (even at subsidised rates) for running their lift irrigation pumps. In the last decade, a great deal of the wrath of the farmers’ movement has been directed at the functioning of the APC and its successor, the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP), because it was often found to recommend prices that prevailed in the market two to three years back, rather than perform the task it was meant to — namely fix prices realistically so that farmers get adequate returns for their crops. Today, the support/ procurement prices announced by the CACP have the effect not so much of providing the basic minimum that a farmer must get for a particular crop, but rather of ensuring that even in the “open market”, traders need never pay more than the prices determined by the government.

Agricultural Exports Discouraged: Worse still are the restrictions on agricultural export. The export of cotton is tightly controlled with yearly quotas released in small instalments over the cotton year. In addition, such exports are subject to a minimum export price fixed by the textile commissioner. Thus Indian cotton producers are not allowed to compete freely in the international market This despite the fact that there is a big demand for the new varieties of long staple cotton now being produced in India and our cotton fetches higher prices than that of most other cotton exporting countries.

Agricultural Exports Discouraged: Worse still are the restrictions on agricultural export. The export of cotton is tightly controlled with yearly quotas released in small instalments over the cotton year. In addition, such exports are subject to a minimum export price fixed by the textile commissioner. Thus Indian cotton producers are not allowed to compete freely in the international market This despite the fact that there is a big demand for the new varieties of long staple cotton now being produced in India and our cotton fetches higher prices than that of most other cotton exporting countries.

If these two controls were to be removed, India could be exporting a minimum of 15 lakh bales of cotton. Why is this not allowed? Simply to ensure a cheap, assured supply of cotton to our forever sick textile industry, which has remained sick despite the government providing protection to it by forbidding import of foreign textiles while allowing it to freely import synthetic fibre to cut down prices of raw cotton produced in India.

n fact, this year the price of cotton has slumped by Rs 300 to Rs 400 per tonne as compared to the same time last year because of low domestic demand. The weak textile industry is neither in a position to buy fresh cotton nor pay the overdues of the previous years without massive subsidies.

he experts in Punjab and Haryana as also the Northern Indian Cotton Growers Union apprehend that if the government delays allowing the export of surplus cotton, farmers may stop growing cotton even in the districts covered under the World Bank-aided intensive cotton development programme. (Economic Times, December 16, 1992).

Farmers suffer from recurring droughts but the urban Farmers suffer from recurring droughts but the urbanpopulation does not starve during periods of crop failure |

Even where permitted, external trade is subject to stringent government regulations. Export of wheat is subject to ceiling fixed by the government and administered through Agriculture Processed Food Products Exports Development Authority (APEDA). Basmati rice can be sent out under open general licence but is subject to a minimum export price. NonBasmati rice cannot be exported beyond the ceiling fixed by the government. Export of onions and cotton have to be channelised through the bureaucratic and corrupt National Agricultural Cooperative Marketing Federation of India (NAFED). Even the export of nigerseed, for which there is no domestic demand, has to be channelised through NAFED and TRIFED despite complaints from foreign buyers of poor quality supplies and unprofessional approach to exports, leading to stagnation of export volume.

Excuses for Discouraging Agricultural Exports: The policy of export restrictions on agriculture is based on two tenets which have had extremely adverse consequences not only for agriculture but the entire economy. The agricultural produce is supposed to be exported only when the production is perceived as being more than adequate to meet all the local demands. Pressures by secondary and tertiary sectors to keep the prices of their raw materials, low have generally resulted in bans on the export of even surplus production. Mill owners have systematically manipulated production and consumption statistics to create a bogey of scarcity to justify imports and bans on the export of cotton. This, now-on-now-off-with-a small-trickle-quotas-export policy has been disastrous for the credibility of Indian exporters of agricultural produce. The vicissitudes of this policy has cost India precious markets.

The second tenet holds that export of value added articles is to be preferred in all cases to that of primary produce. The hypothesis is not necessarily true, particularly if the cost added exceeds the value added as happens in most cases where the plant, machinery and technology are imported, making our supposedly value added goods uncompetitive on account of both price and their being shoddy imitations of western industrial goods. In reality, there is no conflict between the export of value added goods and the raw agricultural produce. The USA leads in both these categories. So do France and Italy. This policy of encouraging the crippled industrial sector and discouraging the competent agricultural sector has resulted in India today being counted as one of the world’s basket cases. All this, when the governments of most developed countries aggressively pursue the interests of their farming communities by helping them find export markets through various devices. In our country, the government has been actively blocking the way of farmers, preventing them from competing in the international market. Instead, it has been providing all kinds of incentives to the industrial sector, such as protected markets within India through high tariff walls and supplies of cheap raw materials, encouraging it to become parasitic and incompetent. Even after the recent reduction, India’s tariff rate for industrial goods, at 85 per cent, is the highest in the world. For years the industrialists were even given cash incentives if they managed to export. But there is hardly any demand for Indian industrial goods as they are extremely shoddy and uncompetitively priced. It is our basmati rice, wheat, cotton, mangoes, new varieties of seedless grapes and a host of other agricultural products which are capable of competing successfully in foreign markets and earning the foreign exchange necessary to bail the country out of its economic crisis.

The Economic Drain of Peasantry: The British colonial raj was based on the direct economic drain of the peasantry through brutally high taxation which led to large scale pauperisation and landlessness. The brown sahibs who took over from the British were smart enough to remove land revenue as a form of taxation. Instead, they opted for indirect forms of taxation by forcing unfair terms of trade on agricultural producers.

According to an estimate by Dilip Swamy and Ashok Gulati, in the decade of the ’70s the peasantry was drained of Rs 45,000 crores (at March 1986 prices) through unfavourable terms of trade manipulated by government controls. This is a form of indirect taxation. They estimate that at present this form of economic drainage is likely to be close to Rs 7,000 to 8,000 crores a year. The spokesmen of the farmers’ movement calculate the quantum of the economic drain at around Rs 12,000 crores per year because the former estimate is based on the highly inadequate Agricultural Prices Commission data.

Yet the bureaucracy and the urban intelligentsia never tire of complaining against the pampering of the peasantry and justifying controls on the farmers on the grounds that the farm sector does not pay income tax. Some of the leading voices within the peasant movement have for long been demanding the “honour and privilege” of paying income tax. The government has avoided imposing income tax on the peasantry because it will bring out the sad truth that only a minuscule section of farmers have incomes large enough to qualify even for the bottom rungs of the tax paying bracket.

Today it is only the black money possessing urban elite (doctors, lawyers, politicians, bureaucrats and businessmen) who are benefiting from income tax exemption of the farm sector. They invest their ill gotten wealth into buying huge estates and build luxurious palaces of the kind that have mushroomed in Delhi’s Sainik Farm area. They escape paying taxes on this by having phoney poultry or dairy farms with five and a half chickens or one and a half cows or a small patch of land set aside for supplying to five-star hotels exotic vegetables such as avocadoes and asparagus, grown by hiring low paid malis. If income tax is introduced in the farm sector, it is these worthies who are going to be adversely affected — not the real farmers, because those who are really living by working on the land are too poor to be tax worthy.

|

We are all here, Sir—fertilizer supplier, pest controller, R.K. Laxman, Times of India |

Producers Starve but Consumers Thrive: Our policymakers are never tired of repeating that they follow these policies with a view to protecting the interests of the poor, helpless consumer, for if they lifted restrictions on agriculture, prices of food would shoot up. Grain procurement, in particular, is justified in the name of providing cheap food through the PDS. That this is far from the truth becomes evident when we consider that 80 per cent of those living below the poverty line live in villages, whereas the vast majority (80 per cent) of PDS outlets are in urban areas. The cheap ration hardly ever reaches the poor landless labourers in whose name government justifies its antifarmer policies. Instead, it is cornered by the urban upper and middle class and their servants, lower middle classes and a small segment of the urban poor. It is common in cities for the well off families in cities to enter into an arrangement with their servants whereby they take the servant family’s ration sugar in return for allowing the latter to take their quota of cheap foodgrains.

f the government were serious about reaching the really poor it should withdraw the benefits of PDS from the better off urban groups and focus mainly on the rural poor because the incomes of the urban poor are far higher than those of the rural poor. By linking the PDS to Food for Work programmes, the government can ensure that the subsidised food actually reaches the needy. If it has to provide cheap foodgrains to the urban poor, it can do so by supplying low priced but highly nutritious coarse grains such as jowar and bajra which currently sell at far lower prices in the international market than wheat and rice.

The truth is that the food prices are being kept low in order to confer on urban industrial interests the advantages of low wages and cheap raw materials. Those who complain against rising foodgrain prices need to remember that the prices of industrial goods have risen many more times in this period. In 1990-91, the purchasing power of wheat was only 67.6 per cent of its 1970-71 value. In comparison, the wages in the urban sector have risen substantially.

Who Benefits from Fertiliser Subsidies in India: For years the government has propagated the myth that the farm sector is heavily subsidised by being supplied cheap electricity, water and fertilisers. The fertiliser subsidy, in particular, has been cited as an example of the unhealthy clout of the peasantry. Actually, far from helping the peasantry, this subsidy is designed to help the already bloated fertiliser industry, as well as the urban consumer to get foodgrains at artificially fixed prices.

Chemical and petroleum-based fertilisers were pushed down farmers’ throats through a massive propaganda campaign by the government agencies in order to ensure a certain level of self-sufficiency in food production. Fertiliser prices were kept controlled in order to coax the farmers into using them to bring about dramatic increases in food output. That is why there was no increase in fertiliser prices from 1981 to 1991. On the other hand, the fertiliser industry was assured large subsidies to meet the deficit between the fixed sale price and the supposed cost of production. This is called the Retention Price Scheme (RPS). In order to extract more and more by way of subsidies, the fertiliser industries began to devise ever newer tricks, such as quoting inflated figures for the initial investment as well as various running costs of operation. They had no incentive to be economically efficient. From a Rs 500 crore subsidy in 1981, the figure shot up to Rs 5,000 crore in 1991. During this period the fertiliser consumption doubled.

Despite this heavy subsidy (which is now being withdrawn), the fertiliser prices in India are higher than those prevailing in most parts of the world. If we base our calculation on the number of kilos of wheat or rice required to purchase one kilo of fertiliser, we find that our fertiliser prices are higher than even in the neighbouring Bangladesh and Pakistan, let alone in those developed economies which give heavy subsidies to agriculture.

The following table shows the amount of paddy required to pay for 1 kg of nitrogen-based fertiliser by farmers in various countries during 1988 :

| Pakistan | South Korea | Japan | Philippines | France |

| 1.97 kgs | 0.76 kg | 0.34 kg | 2.25 kg | 1.82 kg |

“Indian farmers paid the highest at 3.19 kg for 1 kg of nitrogen.”

The policy of RPS has resulted in insulating the fertiliser industry from internal competition by assuring it of a guaranteed return on capital investment. This has resulted in an unviable expansion of the production capacity of the fertiliser industry and encouraged a very inefficient utilisation of resources. Industrialists can afford to inflate plant costs as long as they meet with government-set quotas. This policy rewards bad investment instead of penalising it and discourages the industry from upgrading technology to be cost-efficient. By permitting it to produce fertilisers at a cost much higher than its import parity price, the government is providing it implicit subsidies.

In addition, this industry receives an explicit subsidy by receiving its feedstocks (such as naptha and fuel oil) at prices much lower than the ones being paid by non-fertiliser users. Thus, the withdrawal of the subsidy on fertilisers will not harm the farmers. It will have the beneficial effect of forcing closure of all those units which function inefficiently and whose output costs the Indian fanner more than a comparable product in international markets. So far the farmers have had to bear the burden of keeping them artificially alive.

Wasteful Irrigation Subsidies: As for irrigation and electricity subsidies, they are indeed heavy and need to be withdrawn but the withdrawal will not serve any useful purpose unless the entire system of management is made cost efficient and viable. Our irrigation potential which was increasing at a much faster rate in the’60s and ’70s has begun to decline dramatically. During the ’80s both the government’s investment as well as the farmer’s investment in agriculture has been on the decline. That is really a danger signal for agriculture. The farmers are unable to invest because the return on investment is very low for most of the crops and the risks too high.

The government investment is coming down because it has frittered away huge amounts in the inefficiently run water and electricity boards. Today even the operational and maintenance expenses of these two inputs are not being recovered, let alone the capital cost. It takes about Rs 60,000 to 70,000 to irrigate a hectare. To run the system as per economic principles, the government ought to recover at least 10 per cent of the amount annually, whereas the actual recovery is no more than Rs 250-300 per hectare. In Punjab, farmers pay about seven paise per kilowatt as electricity charges. It costs the state government about Rs 1.08 per kilo-watt to distribute electricity. Yet, the farmers are not the real beneficiaries of these subsidies because they are not able to recover fully the costs of these inputs even at subsidised rates from the prices at which they are compelled to sell their produce. In fact, they feel cheated, because the bureaucratic management of irrigation and the power sector is indeed faulty and wasteful. Corruption and very poor maintenance ensure very low productivity of the system. Erratic supplies keep farmers forever on tenterhooks about when and how much water or power supply they will get. These prices could be easily increased if the farmers could rely on it and recover the costs.

Who Subsidises Whom? Even if one were to concede, for argument’s sake, that Indian farmers are actually subsidised, our bureaucrats and politicians have no moral right to oppose subsidies to agriculture. If subsidies are defined as the difference between what you contribute to and what you take out of the social cake, then the salary earners in the government services are the recipients of they heaviest subsidies. Their overall economic contribution to society is, if anything, negative because of the enormous nuisance value they have acquired and the mess they have made of our economy. They are recipients not just of huge subsidies but also free luxuries, which include free palatial bungalows, free telephones, with bills running into thousands every month, free cars, prime land provided to their housing cooperatives at far below market prices, cheap house loans and car loans, if they want to buy one of their own in addition to the free official vehicles and homes provided. All this comes along with fat salaries and a million opportunities for loot and plunder. Likewise, teachers, bank and public sector employees get a variety of perks, including free holiday allowances for their entire families. Their children get highly subsidised university education (the fee charged by the colleges and universities for children of the urban elite does not cover even five per cent of the costs involved) and even subsidised transport (bus passes for students of metropolitan cities are so low priced— it amounts to virtually free travel) and yet nothing gets these sections more agitated than the supposed subsidy to the farm sector. This is a good example of our tendency to despise those whom we exploit most. The relationship and attitude of the urban elite towards the peasantry is typically that of colonisers. It is immoral for us to use the sad plight of the landless and urban poor as an excuse for the continued exploitation of the peasantry for our own direct benefits.

If Only Farmers were Rich!: It is not just the landless who work as wage labour. A large proportion of those who seek wage labour is poor peasants. This is due to the fact that the prices they get from the sale of their produce do not ensure year-round subsistence. They would benefit more by a rise in the price of crops they produce rather than food prices being kept low. The government’s own records show that dryland farmers holding up to 25 acres have come to seek work at Employment Guarantee Scheme sites during drought years. Why? Because during “normal” years they are not able to save enough to last out even one bad harvest. Compare this to the European farmers, who can’t do any farming for almost half the year because of heavy snow and yet are assured of year-round decent standard of living.

Peasant women from a household harvesting wheat Peasant women from a household harvesting wheat |

What is the maximum income an honest hardworking, efficient farmer can attain? For example, let us take the case of a cash crop growing farmer in Maharashtra, for whom the land ceiling is fixed at 18 acres for irrigated land. Out of this, theoretically, only one-third can be used for sugarcane plantation because one can’t get irrigation water for more than that amount. But even if we calculate on the basis of the entire landholding being under sugarcane, a proficient farm family can get no more than Rs 3,000 per acre as their profit margin, amounting to no more than an annual income of Rs 54,000 or Rs 4,500 per month. This is on the higher side. Thus, this cash crop growing “ rich farmer” earns no more than a bank clerk. The income involves the labour of the entire peasant family, including children, not just that of one earning member as in urban families. For a dryland farmer, the land ceiling is fixed at 54 acres. For such a farm family a net income of Rs 300 per acre per year, amounting to Rs 16,200 for all of 54 acres, would be considered exceptional. In Delhi, a cycle-rickshaw puller probably earns that much by his own labour alone.

In the case of wheat, the best estimates of profit per hectare (two and a half acres) do not exceed Rs 2,000 per crop per acre. Thus, the half-yearly income for the maximum permissible land holding of 18 acres in Punjab would amount to little more than Rs 14,000. The maximum permissible land holding of 18 acres even in a fertile and prosperous state like Punjab would represent a value of Rs 18 lakh at the most. This is equal the value of an ordinary middle-class flat of the kind owned by section officers in the government of India. Why don’t Our policymakers impose similar “ceilings” on urban incomes, including their own salaries and perks, for that will at least ensure the removal of obscene economic disparities in our country?

Only Farmers Must Stay Poor: But that is obviously not the goal of our “socialist” pattern of development which put the interests of urban consumers above the interests of rural producers. The food secretary defended the recent wheat import thus: “If at all this import has adversely affected anybody, it is the handful of big farmers who held back wheat in anticipation of rise in prices in the post rabi marketing season.” (Times of India, November 12, 1992). He could get away with such trivialisation of the problem because of a deep-seated prejudice against the peasantry among the urban intelligentsia, who have for long justified destructive anti-agriculture policies in the name of curbing the power of the rich ‘kulak’ farmer. In fact, the term “rich farmer” is almost always used by urban intellectuals as a pejorative. They would never think of opposing the efforts of the urban working class to become well off.

We don’t mind rich teachers, rich lawyers and rich doctors, rich journalists, rich bureaucrats or well off bank employees. But it is politically fashionable to dread the prospect of farmers becoming rich. Do we want the peasantry to stay forever poor?

Farmers getting rich by farming alone is not even a distant prospect. All over the world, people in the industrial and service sector have relatively far higher incomes and opportunities for accumulating wealth than those confined to agriculture. Yet any sign of prosperity among the fanning community upsets our policymakers as well as the urban elite and brings forth harangues against the deadly power of the “rural elite”. The sight of Amul Cheese or Maggi ketchup in a village shop is for them a sign of spread of degenerate consumer culture, even while they import their own cheese, sauces and dressings from France and Italy. They justify their anger at the farmer, saying they do not pay adequate wages to the farm labour. This is a phoney concern because they are not willing to pay them statutory minimum wages when the impoverished peasants and land-less poor come to cities and work as domestic servants and chowkidars in the homes of the same urban elite who claim concern for the poor while they are in faraway villages. They will haggle for every 50 paise with a rickshaw driver but do not feel pinched paying Rs 25 for a pot of coffee in a five-star hotel. It is very convenient to rave and rant about low agricultural wages because they have to go out of the peasantry’s pockets, not our own. If we want to contribute to the desired increase in the wage rates of agricultural labour, we have to be willing to pay higher prices, at least in the short run, for farm produce. In the long run, food prices are likely to fall if production rises significantly.

Undoubtedly, there is a small number of big landlords who hold vast estates. But these are not farmers. They are mostly rentiers who have managed to defy ceiling laws because of their political clout, as is the case with our present prime minister’s family. Such people ought to be dealt with as lawbreakers, not farmers.

Natural Way to Economic Growth: Rather than mopping up the agricultural surplus for industrial development in urban centres by following the Soviet model, if our I policy-makers had minimised the obstacles in the way of our farming population, our country’s economy would not be in the shambles that it is today. The innovativeness and the enterprise of the Punjab farmer during the late ’60s when he was provided with price incentives, effectively smashed the stereotype of indolent Indian farmer lacking high entrepreneurial spirit and skills. It has been commonly observed that when allowed to retain surpluses, farmers use the incremental incomes in a fairly rational manner.

Their order of priorities tends to be as follows;

(a) Pay off private debts and discharge obligations like marriages, especially of daughters;

(b) Increase acreage under the paying crops;

(c) Invest in improvement of land, water, energy supply as well as in the improvement of the quality of other inputs.

You don’t have to promise them anything, Sir. This is not You don’t have to promise them anything, Sir. This is notwhat has been declared as the famine area — it is further up! R.K. Laxman, Times of India |

These investments in agriculture have an extremely positive consequence in so far as they lead to a significant rise in rural wages, accompanied by the increased availability of work. In addition, the resultant increase in agricultural production brings in greater stability in prices by lowering of off-season prices. Retention of surpluses in rural areas allows farmers to diversify into nonagricultural activities as happened in Japan and also nearer home in Punjab. This latter represents a model of people-based small-scale industrialisation leading to a dramatic increase in wages and incomes to the extent that people from diverse states migrate to Punjab for work. In contrast, wage rates and employment potential in both rural and urban Bihar remain dismally poor despite this state being the heartland of heavy industry and a possessor of rich mineral and forest resources. It is noteworthy that Bihar has the maximum state investment in the industrial sector and Punjab the least.

Societies which pursue pro-farmer policies have been able to industrialise much faster and better than those that don’t. For example, in Japan, the support prices of paddy were fixed in 1921 at three tunes the international prices. The results are there for all to see. Within no time the Japanese farmers began diversifying into the cottage and small industries, laying a solid foundation for the largescale industrialisation of Japan. South Korea, another example of the same phenomenon, is equally instructive. Between 1951-71, South Korea received massive aid from the US and yet remained poor. In 1971, the government of the country launched on a deliberate pro-farmer policy with heavy subsidies and fixation of remunerative prices for paddy. That is when the South Korean economy began its take-off to become a formidable force in the world economy. This is a more organic and natural route to economic growth, as opposed to the Stalinist or Nehruvian policies of forcibly extracting rural surplus for enforced, top-heavy industrialisation which has resulted in large scale pauperisation of the rural population.

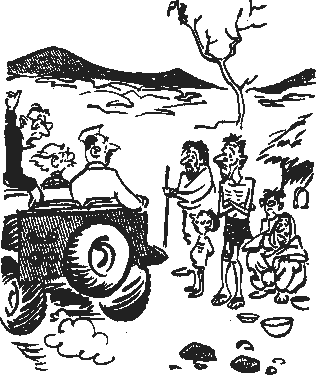

Consequences of Anti-Farmer Policies: Apart from causing rural poverty, anti-farmer policies have endangered the economic and political health of our entire society. It is the prime reason for runaway inflation which is aggravated as our dependence on foreign loans and aid increases. The more we become a dependent economy and the more we borrow, the more we experience the foreign exchange crunch. In addition, the topheavy artificial industrialisation necessitates centralisation and bureaucratisation. Exploitation and neglect of the agricultural sector has resulted in large-scale unemployment and underemployment, leading to a sick variety of urbanisation and painful transfer of population from the over-burdened rural sector to urban areas.

Impoverished peasant families come and work in the most Impoverished peasant families come and work in the mostardous of urban occupations |

No country in the world has made economic progress by following policies which inevitably promote pauperisation of its agriculture-based population. The millions who flock to cities to live in slums and work as rickshaw pullers, domestic servants, rag pickers or stone breakers and take on sundry low paid occupations, are economic refugees from our villages, mostly from poor peasant families. Even the sons of so-called middle and high-income peasants come and work as bus conductors, drivers, peons and so on, since they earn more in these low paid occupations with relatively less arduous work than on their own farms. In short, anyone who can escape agriculture does so. As a result, only those with no options and opportunities are stuck to the tar baby of agriculture and are left behind to take care of that vital sector of our economy which supports about 80 per cent of our population. It is common for men to migrate to cities and leave behind women and children to take whatever care they can of their family land. The resultant small flow of cash incomes earned in cities is crucial for the survival of farm families.

Take the case of J, who along with her mother works as a domestic servant in Delhi. She comes from a peasant family of West Bengal. Most members of her family are working in low paid, menial jobs. The only reason one or two adult members (out of seven) of her family have to stay back in the village on a rotation basis is that if they rent their land and all of them together stay away from the village for an indefinite period of time, their smallholding might be taken away on account of their being declared “absentee landowners.” Apart from the economic consideration that the income from their land is not enough to provide year-round subsistence to her family, J herself does not want to live permanently in the village. Her reason: she finds cooking, cleaning, sweeping and mopping floors, washing clothes and performing endless domestic chores for urban middle-class families much more “easy” than agricultural work.

A traditional saying, common to many of the Indian languages, grades different occupations thus: kheti utkrisht,vyapar madhyam, naukri kanisht, meaning earning one’s livelihood by agriculture (kheti) was considered the most superior of all vocations. Business (vyapar) was of middling value. Service (naukri ) was considered the worst of all. The economic policies of our erstwhile colonial rulers and our present-day masters have succeeded in making the traditional value system turn on its head. Today, being a khetihar (farmer) is considered a curse, where having a naukri, especially if it is sarkari, is considered the biggest boon. People are waging do or die battles for even low-level government jobs, as was demonstrated by the violence accompanying the recent anti-reservation agitation. Hundreds of students went as far as burning themselves to death to protest against caste-based reservations in government employment.

Powerlessness of Indian Peasants: Today our rural population is not only deeply disgruntled but also extremely demoralised because despite decades of powerful peasant movements, both old and new, they have not yet acquired enough clout to oppose the anti-farmer policies of our government and the accompanying misleading propaganda against the peasantry. This despite the fact that more than half of the Members of Parliament hail from rural backgrounds. Evidently, farmers’ sons cease to be interested in agriculture no sooner than their economic interests are divorced from it.

Farmers have had to organise massive agitations by mobilising lakhs of people for protest demonstrations to get their voices heard by policymakers sitting in various bhavans of Delhi. They have had to organise themselves into large vote banks to wrest even nominal concessions for agriculture. However, our industrialists manage to manipulate government policies in their own favour and extract large concessions through simply bribing, wining and dining bureaucrats and politicians — and that too not out of their own pockets. These expenses are included in the ‘cost of production’ of the goods produced and incorporated as ‘entertainment allowance’ given to their business executives and passed on to the consumer.

Bridging the Rural-Urban Divide: Given the terms of trade between urban and rural India and given the artificially depressed prices of agricultural produce in relation to industrial goods, even a farm family with a maximum holding permissible under the ceiling laws and producing the supposed lucrative cash crops cannot become “rich” unless it has other sources of income.

Rustam Vania Rustam Vania |

In the last many years I have visited scores of villages in India. I have never come across a single instance whereby a rural family was able to amass wealth solely through agriculture. The “rich” families in any village ait those in which at least some members have employment, Professional or business interest or political power that comes with outside connections. A study on fuel rights done in a Gujarat village by Priya Deshingkar published in this issue of Manushi highlights that the wealth of the Patel community is linked to its political clout and its involvement with diamond polishing, paper mills, real estate and other business and industrial ventures, as well as overseas connections which bring foreign remittances. An average peasant family would prefer to have a son employed in a low-level government job as a peon or a driver rather than working on the farm. Even a supposedly “big” farmer cannot earn as much as a government school teacher if he is dependent only on agriculture.

Unless our farmers have the possibility and opportunity of improving their life, on par with the urban citizens, India will not be able to make any substantial progress. Let us not practice our radicalism at the cost of the peasantry. Given the nature of hard work that goes into farming, the peasantry deserves to be well off more than anybody else. It is they who are being denied this opportunity more than anybody else. For if there were indeed enough rich farmers, our villages would not be in the sorry state that they are in, lacking in even basic amenities like an assured year-round supply of drinking water and facilities for primary health care.

In 1951, the ratio between agrarian and non-agrarian incomes was 1:1.4. In the decades after Independence, this gap between rural and urban incomes has increased substantially. In 1988, it was reported to be 1:2.8 at constant prices and 1:6.2 at current prices. The gap is likely to have increased further. Between 1951 and 1989, the gross domestic product (GDP) in agriculture as a proportion of total GDP came down from 66 per cent to 27 per cent. As against this, during this period the agrarian population remained steady at around 70 per cent. Over the ’80s, the gross capital formation in agriculture as a proportion of total capital formation in the economy has tended to decline markedly from 18 per cent in the 1980- 81 to less than 10 per cent now.

The rural sector, which caters to almost 80 per cent of India’s population, gets 25 per cent of total electricity produced in the country, one-third of the education budget and less than one-fourth of the health facilities. The child mortality rate in villages is almost double that of cities. The rural literacy rate is almost half that in urban areas.

Several studies have shown that the average length of each workday for most peasant women across the country, including those in the supposedly wealthy Punjab, is 15-16 hours. This includes about six hours on domestic work, including tending the animals and 8-10 hours of work in the fields doing extremely arduous work. This backbreaking drudgery cannot be reduced if agriculture does not become a more paying proposition. Likewise, children, especially girls from agricultural households, cannot make use of educational opportunities, even when they exist, if the majority of peasant families remain so poor that they cannot dispense with the labour of their children.

Additional Measures that Would Help: Our rural economy has been so severely exploited, especially since British colonisation, that it has resulted in the denudation of capital stock in agriculture over a prolonged period. We need to make amends for this by rehauling our overall economic policies in favour of the agricultural sector, even if it means a short term setback to the interests of the well-off urban consumers. After a brief upsurge during the years of the green revolution, investment in agriculture has been falling and moving towards the urban sector because the rate of returns in the trade and industry are disproportionately high as compared to that in agriculture.

A change in investment pattern is urgently required. This cannot happen unless we allow agriculture to generate more profits. Hence my examination of the agrarian question focuses overwhelmingly on the price question. This is not to argue that lifting of price controls will take care of all the problems of the agrarian sector. In fact, the wild fluctuations in international prices of farm produce have ruined many small farmers in many countries. Therefore, some amount of state interventions are necessary. But these interventions ought to function more as a protective buffer for our farmers rather than act as crippling restrictions on them.

My son, Sir? Oh, he is doing very well, My son, Sir? Oh, he is doing very well,thank you. He is a beggar in Bombay! R.K. Laxman, Times of India |

Apart from removing market restrictions, we need urgent action on two additional fronts: infrastructural development and technological innovation. Among other things, this will include much greater emphasis and investment on agricultural research, not through bureaucratic run institutions but through direct involvement of the farming community in both conceptualising and carrying out the research. The farmers have the ability to upgrade agricultural technology more than the best of mere lab-smart scientists. Unless the farmers, especially the women among them, are allowed the full opportunity for further up-gradation of those skills which they have honed over generations, we cannot affect meaningful improvements in agriculture. Research specialists ought not to be ‘government servants’ but rather work as field-oriented consultants advising farmers on a ‘share in incremental’ production basis.

Simultaneously, we will need to rehaul our transport system in a way that villages have easy access to markets and services. In addition, better storage facilities at the village level will help the farmers to diversify into the processing of farm produce thus taking the pressure away from agriculture into small scale industries.

Our irrigation system also needs substantial expansion and freedom from the bureaucratic stranglehold, farmers ought to be made co-sharers of the local irrigation networks through the issue of water bonds so that they are involved in planning, maintenance, supervision and expansion of the system. The will help fanners undertake effective environment conservation programmes which also need to be freed from bureaucratic mismanagement.

Given the heavy risks involved in agriculture, there ought to be widespread introduction of commercial insurance, on-field to field basis for all crops as, also more scientific input into accurate weather predictions.

This is by no means an exhaustive list but only a rough indication of areas that ought to receive priority attention in our planning processes.

In Conclusion: No country in the world has made economic progress without ensuring the economic sustainability of agriculture. We can no longer afford to ignore the danger signals. Our top-heavy model of industrialisation through the “commanding heights” theory of the economy has proven a dismal failure.

- If we have to get out of our economic crises, we have to change the unfavourable terms of trade imposed on agriculture. This will help bring about a change of investment pattern and help resources flow towards the relatively more efficient agrarian sector. Neither our industry, nor IMF and World Bank loans can bail us out of the resource crunch. The agrarian sector shows the capacity to do so by being able to produce a range of goods at internationally competitive prices, despite all the hurdles placed in its way.

- The peasantry needs to be freed from the clutches of the bureaucracy far more than our industrialists who have thrived on the licence-permit raj by perfecting the art of corruption and bribery in order to manipulate economic decisions in their favour. The bias against agriculture and rural India is a major reason for our present economic crisis. Unless we combat this bias actively, India will continue to be counted as one of the economic failures of the world.

- The present regime of restrictions on agriculture in India has only benefited the much better off urban population at the cost of the agriculture-based population — both the peasantry and the landless. They will not need “development aid” nor do they need “subsidies” if the urban elite stops putting obstacles in their attempts to struggle out of poverty. Subsidies have not done anything but harm the farmers because through price controls and unfavourable terms of trade we have extracted far more than what is given through subsidies. All those who wish to see our villages rich and prosperous and not on the brink of subsistence, as the self-serving urban elite would have them remain, need to help the peasantry get the government off its back.

- Those of us who are concerned with the plight of the landless poor ought to realise that their wages can rise only if farming becomes a remunerative activity. If agriculture is in shambles, there is no way we can implement statutory minimum wages in rural areas. If agriculture is prosperous, the landless poor can get year-round employment in the villages themselves and not have to migrate to the cities in search of work. If the flow of immiserated people from our villages does not halt, our cities will become even more unviable than at present.

- The excessive pressure on the land can be reduced only if agriculture begins to yield enough surplus so that farmers begin to diversify into other forms of productive activity such as food processing and other small-scale industry. Easing the overpressure on land is a precondition for effective environment conservation programmes.

- We need to the link the PDS of subsidised food with Food for Work Programmes and link the latter to building permanent social assets in rural areas, such as roads that last (not the kind that get washed away with every rain) and locally controlled environment conservation programmes.

- Food prices cannot come down if we stay dependent on imports. They can come down only if domestic production goes up substantially, which can happen only if the farmers are allowed their legitimate share in the economic advancement of the country.

A peasant woman and her children cross-pollinating A peasant woman and her children cross-pollinatingcotton to obtain the hybrid |

The opposition of urban intelligentsia to freeing agriculture from crippling state controls seems motivated by short term self-interest parading as ‘national interest’. The long-term self-interest of even the urban elite lies in supporting the interest of those who constitute the majority of India’s population. For if the living conditions of 80 per cent of our population do not keep pace with that of the urban elite, the latter will have to deal with pauperised, disgruntled millions invading those urban centres which are islands of opulence. Since all of these millions can not be absorbed in cities even as domestic servants and rickshaw pullers, many will inevitably take to crime as a way of survival.

Our film industry has been giving us warning signals of the consequences of allowing people’s disgruntlement to go beyond safe limits by churning out a whole flood of films depicting the poor resorting to crime as a way of dealing with social injustice because their attempts at seeking justice through peaceful and legal means are consistently thwarted. The takeover of the peaceful Akali movement of the ’70s and early ’80s by criminal brigades of terrorists inspired by Bhindranwale is the political real-life counterpart of the cheaply depicted warning coming through our film industry. A key demand of the Longowal-led Akali movement was that Punjab farmers be freed of numerous price controls imposed by the central government, especially with regard to the wheat our policymakers cussedly refused to heed the Akali demand for economic decentralisation, which would allow the fanners more say in marketing their products within the country and outside. The failure of this massive, peaceful mobilisation of the Punjab peasantry to get its demands accepted resulted in the movement being hijacked by the lunatic militants. Despite the disaster of Punjab, we do not seem to have learnt to heed the warning signals. Our government continues to resort to cheap gimmickry and token concessions rather than respond to the legitimate grievances articulated through farmers’ movements in different regions of the country. If we fail to reform our agricultural policy in favour of producers, we are likely to unleash many more forces similar to the ones running amok in Punjab.

Post Sript: Development “Aid” Increases Poverty: The number of rural poor in developing countries has jumped by 40 per-cent over the past 20 years, an indication that most international aid programmes have failed. The International Fund for Agricultural Development (DFAD), a UN agency based in Rome, undertook a study on rural poverty in 114 countries with a sizeable rural landholding population. It came to the conclusion that the trickle-down theory of economics and attitudes towards the poor prevents them from getting out of the poverty trap.

The IF AD report makes a strong indictment of “development” based on foreign aid by stating categorically: “The crucial point is that… societies will not need massive infusions of foreign aid as farmers will generate their own savings and invest them in local production.” According to Idris Jazairy, president of IFAD, governments interested in improving the plight of small farmers, should abandon policies of keeping food prices low for urban populations at the expense of rural farmers.